Photographs & Ephemera

This selection of archival documents, compiled from the collections of the Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University and the Library and Archives at Bard College's Center for Curatorial Studies, originally accompanied the essay "What Remains: Art and Archives," by Ann Butler and Marvin J. Taylor. All captions are written by the authors of that essay. The printed exhibition catalogue, Take It or Leave It: Institution, Image, Ideology, is available online in the Hammer Store.

FIG. 1. Judson Memorial Church established an artists' ministry in the late 1940s. By the early 1960s it was the home of Judson Dance Theater, which gave birth to postmodern dance; Judson Poets' Theater; and Judson Gallery. In 1970 the church sponsored an exhibition of works that used the American flag as a focal point. The flag had come to symbolize differing points of view about the Vietnam War. Reverend Howard Moody and three members of the Art Workers Coalition—Jon Hendricks, Faith Ringgold, and Jean Toche—were arrested for desecrating the flag. (See also John Miller's untitled painting of Yvonne Rainer's performance in this archive)

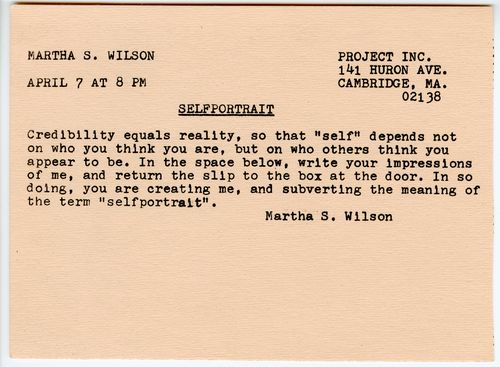

FIG. 2. This invitation card was a central element of Martha Wilson's one-night performance at Project Inc., a storefront in the Boston area.

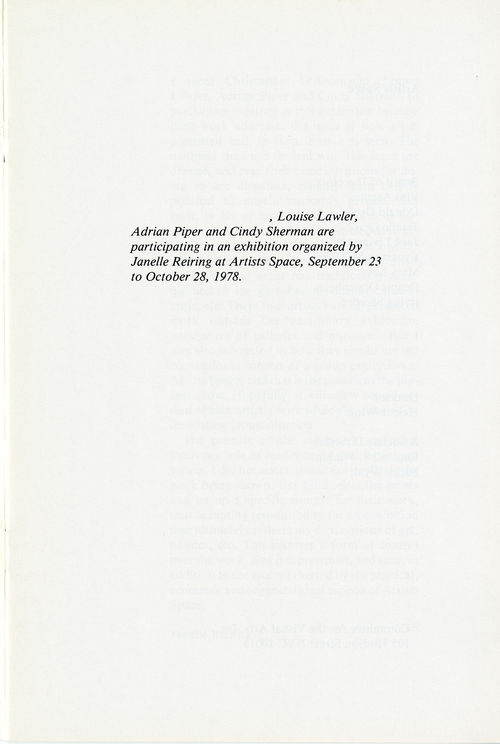

FIG. 3. Curated by Janelle Reiring (who would go on to found the commercial gallery Metro Pictures with Artists Space director Helene Winer), this exhibition at the nonprofit Artists Space included works that explore the ways in which art is presented and informed by context. The four artists engaged strategies like appropriation, intervention, and withdrawal, and in this spirit, Christopher D'Arcangelo requested that his name be removed from the brochure and replaced with blank space.

FIG. 4. Martin Wong was heavily involved in the graffiti scene in New York during the 1980s, though he was not a tagger himself. Wong documented many graffiti artists' works in snapshots. Graffiti art was by its very nature institutional critique. This "piece" was created in one night by Lee Quinones.

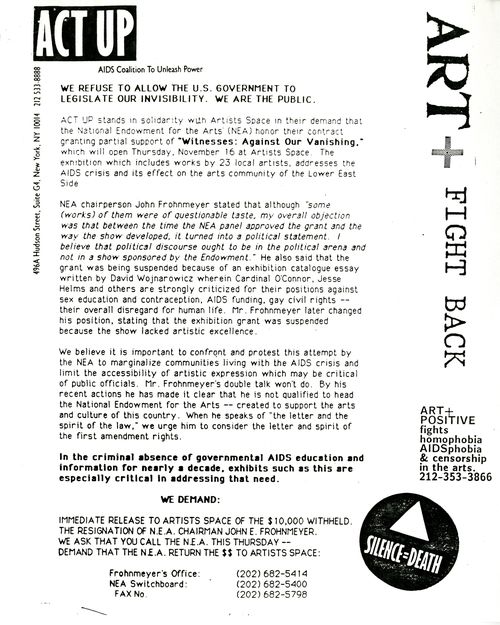

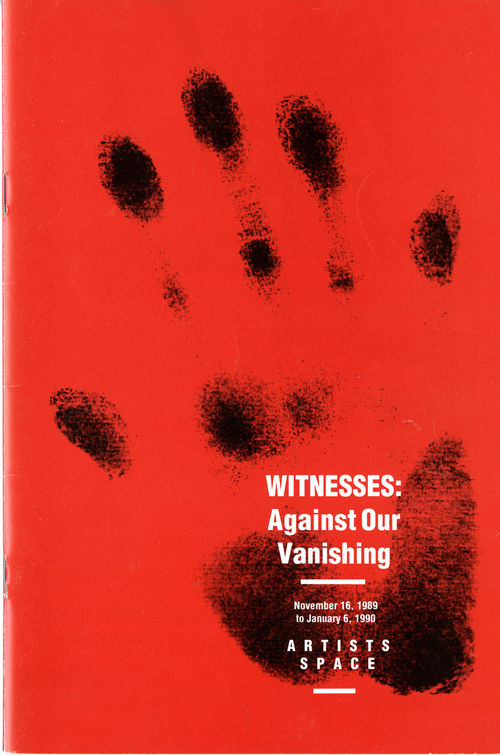

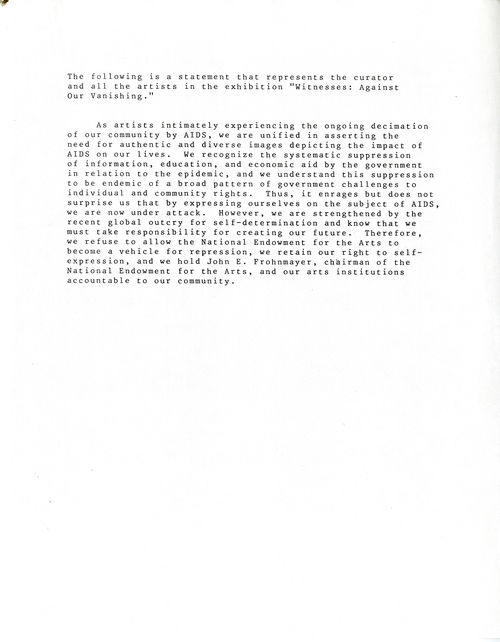

FIGS. 5 & 6. Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing was an exhibition curated by Nan Goldin for Artists Space that ran from November 16, 1989, to January 6, 1990. For the exhibition, Goldin chose works by artists who were directly affected by the AIDS crisis and whose works fearlessly portrayed the ravages of the disease and the widespread cultural indifference to AIDS patients. The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) granted $10,000 to Artists Space for the exhibition, but when the catalogue appeared with an essay by David Wojnarowicz that excoriated politicians and the clergy for their inaction in the face of the crisis—or for their outright attacks on people with AIDS—the NEA came under fire from ultraconservative politicians such as Senator Jesse Helms. John Frohnmayer, the relatively new head of the NEA, rescinded the grant, causing a firestorm throughout the art world and setting the stage for the so-called culture wars that followed.

FIG. 7. Furious at the response of the director of Artists Space to the National Endowment for the Arts' rescinding of funding for Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, the artist David Wojnarowicz wrote this scathing critique of the space and the decisions of its director and board of trustees. Wojnarowicz would become an AIDS activist and a leading spokesman for artists with AIDS. His own works took a more focused turn following the death of his friend and mentor Peter Hujar in 1987 and his own diagnosis with HIV in 1988.

FIG. 8. ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) was formed in 1987 as a direct-action advocacy group in the fight against the AIDS pandemic. Gay men, including prominent artists, were dying in record numbers while the government remained silent. Engaging in civil disobedience and demonstrations, the group garnered much awareness about the AIDS crisis and demanded government response and medical advancement. The culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s coincided with the height of AIDS activism in New York, San Francisco, and other major cities. Artists were often activists themselves, and the strategies of institutional critique that they employed in their work were sometimes directly linked to their commitment to political engagement and social change. In the press release featured here, ACT UP responds to the NEA's rescinding of funding for the exhibition Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, which foregrounded the impact of AIDS on the artistic community.

FIG. 9. This 1991 exhibition at American Fine Arts, Co., consisted of one hundred plaster surrogates by Allan McCollum installed in a single horizontal line on four walls. Gallery employees usually stationed at the front desk were replaced by hired actors, who performed Andrea Fraser's work May I Help You? Using a script written by Fraser, the actors presented twenty-minute monologues for anyone who came to see McCollum's work. Posing as gallerists at the ready to explain the work on view, the performers instead took on six different characters, each with a distinct social position, and articulated a variety of contradictory relationships to the works.

FIG. 10. Installed at American Fine Arts, Co., as part of the 1993 exhibition What Happened to the Institutional Critique?, this work by Mark Dion and the Chicago Urban Ecology Action Group calls attention to the ways social values and ideologies are inscribed within the seemingly impartial spaces of natural history collections, zoos, and urban parks. Organized by James Meyer, the exhibition was a response to the institutionalization of certain types of "political" art.

FIG. 11. This 1993 work by Tom Burr was included in the exhibition What Happened to the Institutional Critique? The piece references an earlier work of Burr's, An American Garden (1993), produced for Park Sonsbeek in Arnhem, the Netherlands, which re-created a section of the Ramble in New York's Central Park, a thickly wooded area of the park long known as a site for gay cruising. This small-scale version of the work, which the artist called "an informational non-site," was installed outside American Fine Arts, Co.'s entrance on Wooster Street.

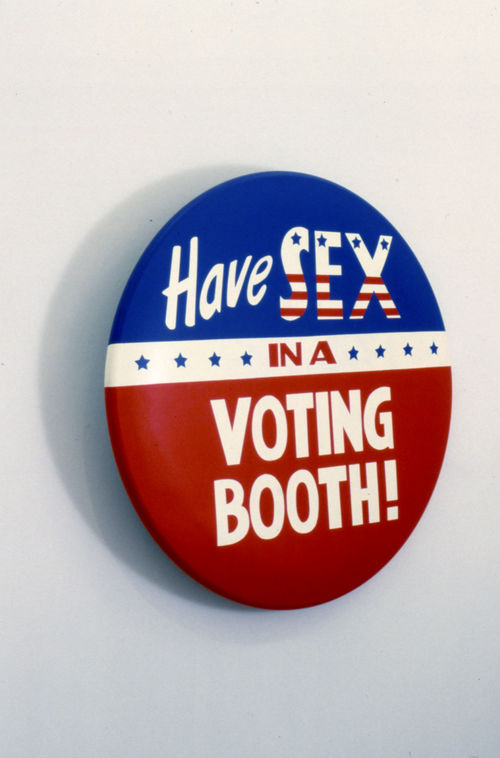

FIG. 12. This work by John Waters was installed at American Fine Arts, Co., as part of the 2004 exhibition Election. Organized by James Meyer as a response to the policies of the Bush administration and the contentious outcome of the 2000 presidential election, the exhibition also served as an homage to the gallery's late founder, Colin de Land (1955–2003). Election was the last exhibition held at American Fine Arts, Co.

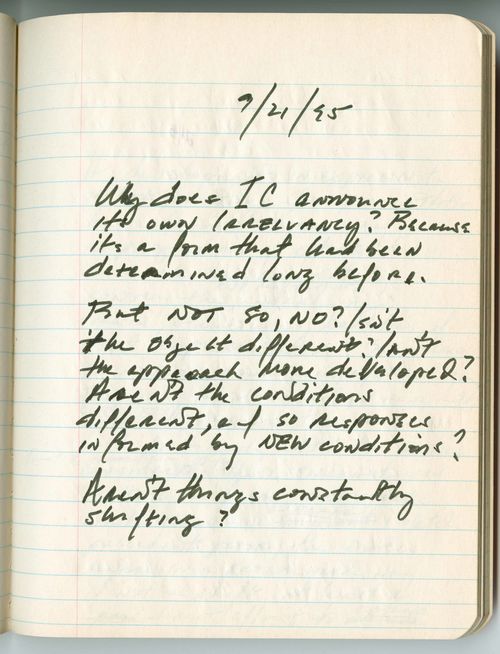

FIG. 13. This entry from 1995 in one of several notebooks kept by the New York art dealer and gallerist Colin de Land discussed the legibility and temporal characteristics of institutional critique. After closing Vox Populi, his gallery in the East Village, de Land opened American Fine Arts, Co., in the then quiet neighborhood of SoHo in 1988. He was more interested in experimentation than in commercial success, and American Fine Arts, Co., became one of the primary spaces in the city devoted to the presentation of large-scale installations, specifically those by artists engaged with institutional critique, including Tom Burr, Peter Fend, and Cady Noland.

![Martin Wong (photographer), Lee Quinones in front of an untitled graffiti piece, [1980s]](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_thumbnail/public/migrated-assets/media/Digital_archives/Take_It_or_Leave_It/Essays/Fales_NYU/martin-wong_lee-quinones-graffiti.jpg.jpeg?itok=3kRFjBG5)

![Martin Wong (photographer), Lee Quinones in front of an untitled graffiti piece, [1980s]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/migrated-assets/media/Digital_archives/Take_It_or_Leave_It/Essays/Fales_NYU/martin-wong_lee-quinones-graffiti.jpg.jpeg?itok=KJOVVsZ9)

![David Wojnarowicz, “Statement from David Wojnarowicz to [Artists Space] Board of Directors, November 17, 1989,” page 1](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_thumbnail/public/migrated-assets/media/Digital_archives/Take_It_or_Leave_It/Essays/Fales_NYU/david-wojnarowicz_statement-artists-space_witnesses_p1.jpg.jpeg?itok=mOuto6Dh)

![David Wojnarowicz, “Statement from David Wojnarowicz to [Artists Space] Board of Directors, November 17, 1989,” page 2](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_thumbnail/public/migrated-assets/media/Digital_archives/Take_It_or_Leave_It/Essays/Fales_NYU/david-wojnarowicz_statement-artists-space_witnesses_p2.jpg.jpeg?itok=J7LdMdME)

![David Wojnarowicz, “Statement from David Wojnarowicz to [Artists Space] Board of Directors, November 17, 1989,” page 3](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_thumbnail/public/migrated-assets/media/Digital_archives/Take_It_or_Leave_It/Essays/Fales_NYU/david-wojnarowicz_statement-artists-space_witnesses_p3.jpg.jpeg?itok=BQr-Swn8)

![David Wojnarowicz, “Statement from David Wojnarowicz to [Artists Space] Board of Directors, November 17, 1989,” page 1](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/migrated-assets/media/Digital_archives/Take_It_or_Leave_It/Essays/Fales_NYU/david-wojnarowicz_statement-artists-space_witnesses_p1.jpg.jpeg?itok=ZUMNLz4G)

![David Wojnarowicz, “Statement from David Wojnarowicz to [Artists Space] Board of Directors, November 17, 1989,” page 2](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/migrated-assets/media/Digital_archives/Take_It_or_Leave_It/Essays/Fales_NYU/david-wojnarowicz_statement-artists-space_witnesses_p2.jpg.jpeg?itok=spWy8kUe)

![David Wojnarowicz, “Statement from David Wojnarowicz to [Artists Space] Board of Directors, November 17, 1989,” page 3](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/migrated-assets/media/Digital_archives/Take_It_or_Leave_It/Essays/Fales_NYU/david-wojnarowicz_statement-artists-space_witnesses_p3.jpg.jpeg?itok=RFinK2qh)