Poetics of Resistance

For contradictory reasons—political as well as cultural in nature—Chile played a central role on the international scene in the 1970s. In 1970 Salvador Allende, the candidate representing the Unidad Popular, a coalition of leftist parties, was elected president in a turn of events that was as exceptional as it was hopeful: Chile represented for the world the possibility of a transition to socialism by democratic means in a peaceful revolution.# The intense involvement of the masses on the urban scene largely revolved around the cultural field. Starting in the late 1960s, the Nueva Canción Chilena movement,# street theater groups, printmaking, urban murals,# signs, and posters indicated that a conception of culture immersed in the urban and popular scene had taken hold. In her song "De cuerpo entero" (1966), Violeta Parra (1917–1967) communicated the political emotion that activated multitudes, placing them at center stage. Perhaps no artistic image conveys the presence of the embodied concepts of the masses and of thirst for transformation more powerfully than América no invoco tu nombre en vano (America, I don't invoke your name in vain), a mural-size painting produced by Gracia Barrios (b. 1927) in 1970.# It was at that juncture that her painting first subscribed to critical realism. The crowd in the image reaches the very edges of the immense canvas; the marching bodies—offset by the white background—blend into a dark mass out of which the faces of men and women peer. The work synthesized what was happening in many cities around Latin America: the citizenry taking to the streets to demand greater representation, more rights, and justice.

But those ideals were not embraced by the entire society, and the lack of consensus grew more patent in March 1973, when the opposition to the Unidad Popular government lost the parliamentary elections. The military coup on September 11 of that year—its most telling image being the Palacio de la Moneda, the Chilean seat of government and president's residence, in flames—put an end to the socialist government. Like thousands of others in Uruguay and in Argentina, Barrios left the country in a process of exile that divided society in two.# Those who stayed were surrounded by violence and repression, facing imprisonment and torture, and those forced to leave Chile had to deal with the uprootedness that exile entailed.

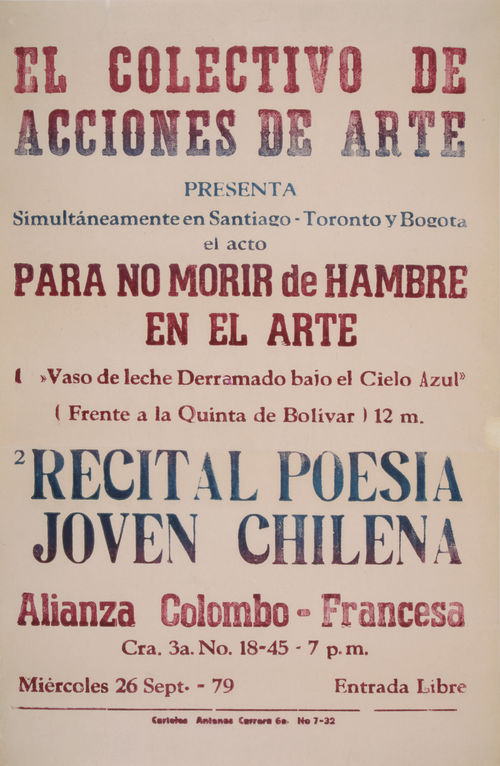

Before and during the socialist administration, Cecilia Vicuña (b. 1948) developed a body of work that linked the sculptural and the poetic. She looked to the transformative power of "precarious" forms—small spatial constructions with elements taken from nature destined to disappear—and of what she called her Diario estúpido (Stupid diary), the erotic poems with a feminist bent that she wrote from 1966 to 1972. During the military coup and shortly before they were to be published by the Pontificia Universidad Católica in Valparaíso, many of those poems disappeared.# These are poems that exalt the body, reject the taboos surrounding female sensuality, and elude a revolutionary discourse that was also sexist. For Vicuña the celebration of pleasure was part of the socialist transformation—a vision made abundantly clear in "Misión" (1971), a poem in which she proposes an investigation geared to making the revolutionary kiss the best kiss in the universe.# During those years she cofounded and formed part of Tribu No, an avant-garde group that staged performances and published manifestos. Along with her life partner at the time, Claudio Bertoni (b. 1946), she also created photographic performances in which objects (a padlock, a razor blade) were placed between the legs of one of her women friends. Vicuña was photographed with a white net on her head, as if she were a piece of fruit, and Bertoni with his face twisted by a piece of rope that seemed to be strangling him. Her text associates torment and birth: "I tied up my boyfriend and wound myself in a net. Life and death are knotted in a thread / the hanged man's rope, / and the umbilical cord." In 1973–74, after she had settled in London, Vicuña was very active in the struggle against the Chilean dictatorship.# In Bogotá in 1979, in conjunction with Para no morir de hambre en el arte (In order not to starve to death in art), an action by the Colectivo de Acciones de Arte, she created the work Vaso de leche, Bogotá (Glass of milk, Bogotá, 1979). The action revolved around milk in a reference to both the Allende administration's policy of distributing half a liter of milk per child per day and an incident in Colombia in which hundreds of children had been poisoned when a private company added water and paint to milk. The work consisted of the simple act of spilling the contents of a glass of white paint with red yarn around it in front of Simón Bolívar's residence in Bogotá. The action was announced by means of a poster put up on the streets (fig. 1).#

Very much a part of the revolutionary movement, women—whether or not they identified as feminists— played a key role in Unidad Popular.# Their antitheses were the women who, in 1972, participated in the pot and pan protests known as the movimiento de las cacerolas, which contributed to the fall of Salvador Allende's constitutionally elected government.# Such women were also crucial to the dictatorship's ideology of the family, as articulated by the Secretaría de la Mujer and the Centro de Madres (CEMA Chile).#

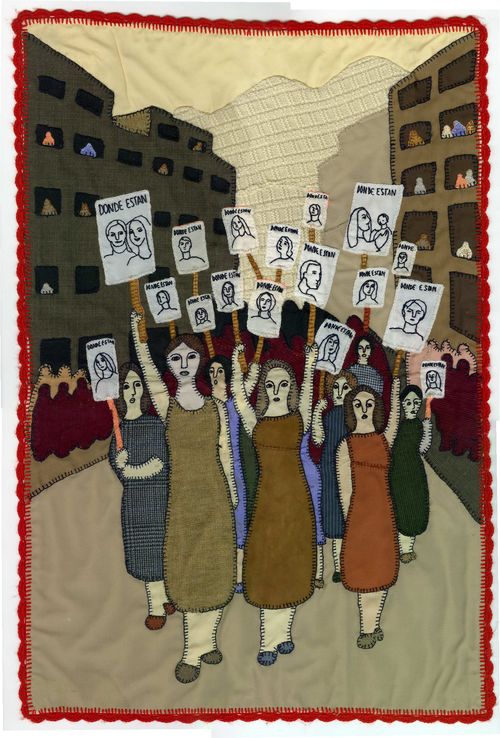

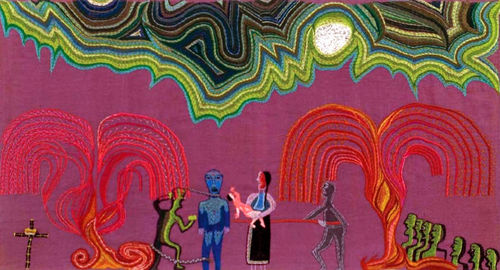

While the years immediately after the coup have been described as a period of absolute cultural paralysis, some signs of resistance did emerge and not only in the sphere of art. Despite repression, more murals were painted—now using spray paint rather than a brush, because it was more immediate and quicker to apply. In 1976 groups of mujeres arpilleras, or "burlap women," were organized. Their works, which consisted of scraps of colored fabric sewn together, addressed social issues (fig. 2).# The origin of those groups, which were supported by the Vicaría de la Solidaridad, lay in the burlap works that Violeta Parra had embroidered in the 1960s (fig. 3). In 1977, when their works were shown at Paulina Waugh Gallery, they were set on fire in an attack on the show.# The activism underlying the images revolved around the Taller de Artes Visuales,# the Agrupación Cultural Universitaria, the Taller 666 theater troupe, and the Departamento Cultural Vicaría Sur. In 1977 the Semana por la Cultura y la Paz was held for the first time at the Cerro San Cristóbal. These various spaces and organizations came together at the Unión Nacional por la Cultura, held in January 1979.# That year, in a climate of growing popular protest, Mujeres por la Vida engaged in "lightning actions" that inquired into the whereabouts of the disappeared.# Thus the control of bodies, spaces, and subjectivities established by the dictatorship was increasingly permeated by forms of insubordination.

Excerpted from Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985. Copyright © 2017 by the Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center, Inc. Published by DelMonico Books, an imprint of Prestel. The full essay can be found in the exhibition catalogue, available here.

Unidad Popular was a coalition of socialists, communists, radicals, the Movimiento de Acción Popular Unitaria, and the Acción Popular Independiente.

The Nueva Canción Chilena was a musical movement in which folklore was renewed through musical innovations. Violeta Parra was one of its major figures. During the Salvador Allende government, groups such as Quilapayún created the celebrated album Cantata Popular Santa María de Iquique. The coup d'état sent many of the members of this musical movement into exile.

Pursuant to a referendum in 1988 in which the "no" vote put an end to the administration of Augusto Pinochet, Chile entered what is known as the transition period, which began when democratically elected president Patricio Aylwin took office (he served from 1990 to 1994). Murals with a pop aesthetic were painted throughout Chile. Active starting in 1968, the Brigadas Ramona Parra, drawn from the membership of the Juventudes Comunistas, painted murals. There were as many as 120 such brigades around the country. Rigoberto Reyes Sánchez, "Arte, política y sociedad en Chile desde 1970 hasta 1979: Una constelación posible," Pacarina del Sur, November 20, 2016, http://www.pacarinadelsur.com/dossier-9/813-arte-politica-y-sociedad-en-chile-desde-1970-hasta-1979-una -constelacion-posible.

Barrios's title, which was also the title of the inaugural exhibition of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Santiago (which was installed in a tent), is a line from Pablo Neruda's emblematic book of poetry Canto general (1950).

Barrios sought exile in Paris with her partner, the artist José Balmes, and their daughter.

The poems from the collection that were saved were published under the title Saborami in England in 1973 by Beau Geste Press, an important publishing house associated with Fluxus, of which Felipe Ehrenberg was codirector. Additional poems have been recovered more recently.

The poem reads: "I propose we take a trip / around the world to be officially designated 'Socialist government research project.' / You and I will be the 'kissers.' / You and I kiss better than anyone in the world. / Having developed a meticulous and carefully researched method for perfecting the kiss. There is no woman who kisses like me. / Nor man who kisses like you. / As THE KISSERS we'll kiss as many people as possible to determine who does it better and learn accordingly from their technique to practice it and bring it back, hastily, to our socialist country, which will be the land of The Kissers."

Thanks to a fellowship from the British Council, Vicuña studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art at University College London before the coup. As a member of Artists for Democracy, founded in 1974, she participated in actions to support the Chilean resistance. The artist's work along those lines has been studied by Paulina Varas, curator of the exhibition Artists for Democracy: El archivo de Cecilia Vicuña, held at the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos and at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago, in 2014.

A film that Vicuña made in 2008 includes archival press images related to the corruption scandal in Colombia and to the action performed by the Colectivo de Acciones de Arte in Santiago, as well as letters from Lotty Rosenfeld inviting her to participate.

Javier Maravall Yáguez, Las mujeres en la izquierda chilena y durante la Unidad Popular y la dictadura militar (1970–1990) (Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 2015).

Julieta Kirkwood, Ser política en Chile: Las feministas y los partidos (Santiago: LOM, 2010), 33.

The aim of the Centro de Madres, an institution created in Chile in 1954, was to enhance the spiritual and material well-being of Chilean women. It was promoted by first ladies and, after the military coup, its head was Lucía Hiriart de Pinochet, the dictator's wife. The center had an extensive network of volunteers, mostly wives of military officers. It was funded by the national lottery until 2006, when a law passed by the senate cut off its funding.

See Arpilleras: Colección del Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos (Santiago: Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos and Ocho Libros, 2012).

Paula Edwards and Antonio de la Fuente, "Arte poblacional: Cuestión de coraje," La bicicleta: Revista chilena de la actividad artística (Santiago), no. 5 (1979): 5.

Created in 1974 pursuant to the dismissal of a group of professors at the Escuela de Bellas Artes, the Taller de Artes Visuales acted as a space where artists could gather and produce work during the dictatorship. One of its founders was Francisco Brugnoli.

The magazine La bicicleta: Revista chilena de la actividad artística (founded 1978) covered what was happening outside the institutional art circuit.

Mujeres por la Vida was a women's social movement that emerged in 1983 in response to the death of Sebastián Acevedo, who set himself on fire after the disappearance of his two children. The movement was formed by women in the opposition from different professional and social backgrounds and with varying political affiliations. It engaged in peaceful "lightning acts" and public marches designed to have a social impact on the effort to restore democracy. The founders of the movement were Mónica González, María Olivia Monckeberg, Marcela Otero, and Patricia Verdugo.