Hammer Projects: Chiharu Shiota

- – This is a past exhibition

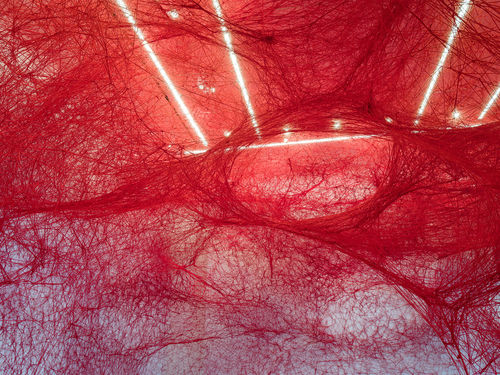

Chiharu Shiota (b. 1972, Osaka) is a Berlin-based artist whose installations, sculpture, and performance art invoke psychogeographic spaces of memory, emotions, and the cyclical nature of life and death. Using red, black, or white yarn as a base material, Shiota often creates meticulously webbed environments that span the length of entire galleries and mimic organic forms such as cobwebs, veins, and fractals. Shiota also includes a range of found objects in her work such as wooden chairs, abandoned shoes, rusted keys, and used dresses as a strategy to implicate the viewer in the artist's personal narratives that are often universal experiences.

Shiota will be the inaugural artist featured in the Hammer’s redesigned lobby and will envelop the area with a unique and visceral installation.

Hammer Projects: Chiharu Shiota is organized by Erin Christovale, curator, with Nika Chilewich, curatorial assistant.

Essay

By Nika Chilewich

The moment people enter my works, I want them to understand what it is to live and what it is to die.

—Chiharu Shiota

A veritable alchemist of her medium, Chiharu Shiota has spent the majority of her career extracting a poetic language from a single material: yarn. In what has been a nearly thirty-year practice of formal distillation, the Japanese artist has developed a transcendent conceptual relationship to her materials. Shiota’s monolithic site-specific landscapes take on questions of time, permanence, presence, and mortality. Matter becomes a pretext for a discussion of the universal nature of subjective experience and the longing that accompanies it. Her vast, ephemeral gestures coopt their surrounding architectural space with abstract lines of yarn woven into fantastical landscapes. The artist’s use of red, black, or white yarn to create monochromatic installations tempers the almost cinematic scope of her formal lyricism.

Shiota approaches physical site as an ideological space, a framework wherein her installations explore the relationships between and within the institutional entities that support the production of each work. Humanist in its approach to the institution, Shiota’s practice engages the museum not as a singular entity but rather as the container for the community of individuals it houses at any given time. A denial of the sort of “uncovering” or indictment of the museum and gallery space that was popularized in the United States in the second half of the twentieth century, Shiota’s work can be seen as a staging of an institutional dance between the individual and the collective body.

Shiota, who purposely offers very little contextualizing information about her work, has referred to her installations as drawings in three-dimensional space, a description that subverts traditional distinctions between artistic mediums and emphasizes the importance of process in her work. Instead of engaging with the traditions of craft or fiber art, she uses her material of choice to access new contemplative states, achieved through the simplicity of a single repeated gesture enacted over time. This meditative, almost spiritual process allows her to trace the relationship between mind, body, and spirit that is awakened when the body comes into contact with the material world. Enacted by a collectivity of bodies at a scale that mirrors that of religious or civic architecture, Shiota’s sculptural drawings attempt to reach beyond the individual toward a more universal conception of human experience.

According to Japanese mythology, an invisible red thread tied to a baby’s finger at birth binds them to a network of people who will play significant roles in their life. Such stories have informed Shiota’s use of yarn, and encounters with her installations, which employ the illusory nature of figurative representation, often take on a mythic quality. This is especially true when everyday objects such as keys, windows, or love letters are woven into her sculptural landscapes, imbuing them with an elegiac narrative tone in which the object invokes the absence of the human form.1

Shiota initially trained as a painter in Japan before continuing her studies in Germany, where she currently resides. One of her first installation works, Becoming Painting (1994), would set the tone for her artistic trajectory by establishing two central components within her work: the use of thread as a singular object of investigation and an embodied, performative artistic positioning of the self within the work. From there she continued to explore and build a lexicon of her own. As her installations grew in scale, she would spend countless hours weaving the thread into itself, moving her hands in and out of the webbed material, positioning the act of weaving—a form of gendered creative labor that has been relegated to the unremunerated margins of our cultural economy because of its association with women—as a complex philosophical and spiritual pursuit.

Shiota’s work embodies a rejection of traditional artistic hierarchies centered on US and European conceptualism, and one can observe an affinity with the legacies of Japan’s post–World War II avant-garde. Her use of performance as a means of depicting the relationship between artistic form and human spirit seems reminiscent of the artistic production of the action-based Gutai group, for example.2 And Shiota’s systematic approach to artistic process, as well as her choice of medium, mirror the measured explorations of artistic material undertaken by the artists associated with Mono-ha. Key to their practices was an awareness of the process through which perception is generated and the affective systems in which it is embedded.3

Although Shiota is not dismissive of the affinities between her work and Japan’s early conceptual histories, she does not cite the experimental movements as having influenced her. She has, however, noted that the artists of this generation were almost exclusively male, a reality that informed her decision to leave Japan.4 A more significant point of departure between Shiota’s practice and those of the postwar Japanese avant-garde is the artist’s celebration of figurative space. Instead of rejecting the relationship that figuration has to Western art making and Eurocentric cultural values, Shiota has harnessed a sense of lyrical beauty and narrative theatricality for its ability to transport the viewer. She uses representational space as a mechanism of seduction, part of an arsenal of tools that she harnesses to transport viewers out of their daily lives and into a more transcendent space of reverence and curiosity.

Exquisitely constructed landscapes are for the artist as much a register of a performance as they are an exploration of foundational concepts of figuration: things like line quality, shadow, density, weight, and scale. Shiota’s works touch on the concept of infinity, as echoed by the hundreds of thousands of strings that make up each piece. Hers is a world-building exercise in which beauty is an invitation to viewers to engage in a collective horizontal exchange. When seen from this vantage point, each installation becomes a sort of theater of interrelatedness between the artist, her team, the institutional community housing the work, and finally its different publics, both live and virtual. They demonstrate a macro-poetic structure created through the revelatory process of repetition. Each work hums with a chorus of phenomenologically charged moves that contain a multitude of entry points capable of dislodging viewers from their quotidian existence and inducing reflection on the evanescence of time and the fleeting yet sacred experience of presence.

It is precisely this analog poetic machine that is the subject of The Network (2023), Shiota’s intervention in the newly remodeled Hammer Lobby. Based on a series of questions the artist asks of her own practice, The Network is her first major installation to reflect on her personal poetics. In lieu of found objects, the work uses form and process to generate a sort of call-and-response between Shiota and the Hammer Museum. By asking questions of its own existence, The Network employs the artist’s visual language and poetic style to draw parallels—points of similarity and tension—between her practice and the communities it involves and the collective histories implicit in the museum’s institutional architecture. The Network is a conversation about the relationships that serve as the foundation of our creative existence, tracing the contours of a shared lived experience and the experiences that have altered the course of our individual and communal lives.

1. Examples of this include House of Windows (2005), The Key in the Hand (2015), and the more recent Letters of Love (2022), in which Shiota asked viewers to submit letters of gratitude for someone in their lives.

2. The Gutai group was founded by Jirō Yoshihara in the 1950s. Today it is arguably the best-known collective to emerge from this period of Japanese art history. For more on these histories, see Mika Yoshitake, “Breaking Through: Shōzō Shimamoto and the Aesthetics of ‘Dakai,’” in Target Practice: Painting under Attack 1949–78 (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 2009), 106–23.

3. Mika Yoshitake, “What Is Mono-Ha?,” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 25 (December 2013): 204.

4. Chiharu Shiota, conversation with the author, January 24, 2023.