Hammer Projects: Jeanine Oleson: Conduct Matters

- – This is a past exhibition

Following her residency at the Hammer Museum, Jeanine Oleson will present a new body of work and performance related to conduction as a material, musical, and social matter.

The New York–based artist Jeanine Oleson (b. 1974, Astoria, OR) works with photography, performance, film, video, sound, and installation, exploring themes including audience, language, spirituality, memory, music, and alienation. Following her recent residency at the Hammer, Oleson presents a work related to research on the conditions of copper usage in late capitalism and the irreconcilable contemporary relationship between bodies, labor, resources, and art. With humor, pathos, and pleasure, the installation includes catalytic instruments and objects that interrelate the body’s function and relationship to materials and representation. It also features a video of an absurdist ensemble performance work based on the production process of copper. A hand-woven rug anchors the project, its composition based on perspectival issues of 3D imaging. The wry sense of humor exhibited in her work belies Oleson’s intellectual rigor and interest in labor, environment, craft, and performance.

Essay

In the fall of 2008 artist Jeanine Oleson made a public work with the quasi-aspirational, Dada-inspired title Greater New York Smudge Cleanse. In an action that unfolded over several days, Oleson and a group of other women carried a ten-foot-long smudge stick (a bound bunch of sage, and the world’s largest such, according to the artist) through the streets of Manhattan, Queens, and Brooklyn with the goal of smoking out such negative forces as pollution in Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal and the gentrification of Manhattan’s West Village (which was driving out queer communities). A gentle gesture for very rough times, the action self-consciously invoked its historical roots, including 1970s feminist practices as well as ancient Native American rituals of purification. Liaising with local groups such as the Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club and intended as direct action in response to then-unfolding political events such as the Exxon Mobil oil spill, as well as historical ones like the Stonewall riots, Oleson crafted an on-the-ground response that was both futile and absurd, yet gamely ambitious.

Part of the power of Oleson’s art lies in the precarious scale of its questions. On the one hand, she confronts big ideas and nearly unmanageable subjects—pollution in the Gowanus, or the enormity of Stonewall’s legacy—with a multidisciplinary practice that combines performance, video, photographs, research, action, and usually sculpture. Performance props such as the enormous sage bundle are important, as sculptural relics that codify or contain whole projects and bodies of research. Oleson makes objects that have an oblique relationship to her subject and yet are the material signifiers of an archive of activities that cycle around a vein of deep research.

Based in New York but always aware of her Northwest Coast, workingclass roots, Oleson is interested in the problem of labor. She is part of a generation of artists whose relationship to language and gender is unstable. Informed by political feminism and its radical ethical systems, but skeptical of its afterlife, Oleson draws on the theoretical work of the queer theorist José Estban Muñoz and his ideas about precarity, as well as the scientist Karen Barad, whose work on queer performativity attempts to uncouple language from occurrences in the natural world, particularly Barad’s writings on “thingification”: “the turning of relations into ‘things,’ ‘entities,’ ‘relata’ [and how this] infects much of the way we understand the world and our relationship to it.”1 The turning of relations into things comes as close as anything to naming Oleson’s strategy, or at least a way of understanding her objects. Oleson is obsessed with certain materials and their transformation through process. Copper, clay, transmission, and conduction—these she wants to understand haptically, that is, through her body. Underlying each project is an attempt to represent the relationship of language to matter, and matter in relationship to bodies and the agency of those bodies. “What are you trying to make?” asks one of the women in the video from the project Figures of Speech. “The pressure to understand,” answers another. What is the need to name a thing? As if it matters.2

The title of this exhibition is Conduct Matters, which, in Oleson’s hands, is as much an edict for our times as it is the instruction that underlies the components of the Hammer Projects exhibition. Of course, like the majority of Americans, she is reeling from the election of a man whose blatantly reprehensible conduct toward women didn’t seem to affect public opinion. Forget feminism; her simple admonition that conduct does indeed matter is a funny yet serious elementary-school warning to anyone who doesn’t understand basic human decency. The puzzle of Oleson’s art is an attempt to communicate through objects and images, but also a gesture of the impossibility of representation in a moment where actions mean nothing and words have taken on a strangely monumental signification. Truth and its cousin, the alternative fact, are confoundingly intertwined.

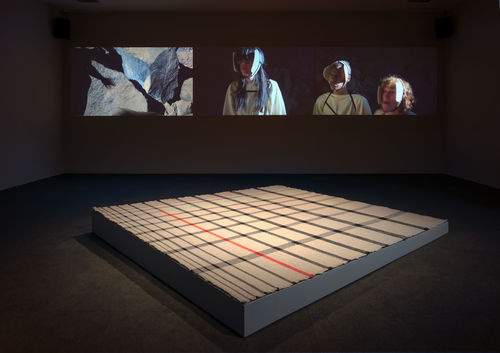

Oleson has for some time been interested in copper as an elemental material of great mystery but also as a product of late capitalism’s design and control. The description of Figures of Speech, the project that immediately precedes and leads to Oleson’s research for Conduct Matters, provides clues to the artist’s thinking. Of her current pursuits she has said, “Mining late capitalism’s alienating effects through material is extraction and labor. . . . I’m making catalytic instruments and objects which alter the body’s function in relationship to representation . . . using their bodies as instruments . . . troubling representation of materiality and images.”3 Crossed Wires (2017), the video featured in the exhibition, is a three-channel work that follows four characters as they explore caves, refineries, the power grid of a city, and an open-pit mine that was a site of a workers’ protest. The piece touches on how late capitalism has isolated workers and disconnected them from nature and the land, a play on Marx’s idea of abstract labor. According to the artist, some of the processes in the work attempt to reinvent labor and make it concrete and visible: reification/thingification.4 Collaborators use their bodies and hands to interact with copper in various forms, drawing a direct relationship between human labor and production. The cave location featured in the film is an intentionally obvious reference to Plato’s cave and the systems of oppression embodied in conventional Western narratives of art and art making. These are the same histories that shaped Oleson as an artist.

In another exterior scene a character gives a speech outside of a mine, comparing the large hole and monumental forms created by the dig to an earthwork. She speaks about site specificity and geological time. The other characters look meaningfully at the speaker and try, very hard, to understand. “The intention, of course, is for us to feel with our body,” she says. What does it mean to feel with our bodies? This is a question Oleson asks over and over. An awkward soliloquy, the monologue was pieced together from texts about Land art by the American artist Robert Smithson, and the obviously spliced dialogue straddles the line between nonsense and artspeak. A fan of ensemble techniques from theater and opera, Oleson often prompts her collaborators with questions (What is the worst job you have ever had?) or improvisations that inspire them to think through language acquisition as a metaphor for the kind of dialogue it might inspire. Both the Land art script and the embedded commentary on labor harken back to the era of the Art Workers’ Coalition, whose important early discussions about artistic labor have informed how we think today about cultural work and its compensation.

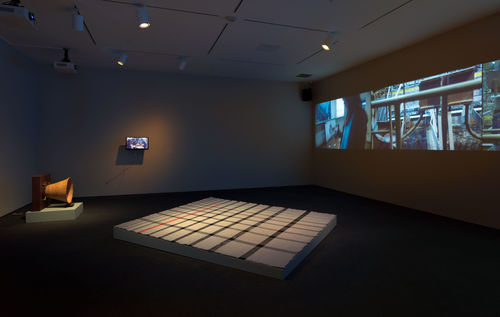

Oleson’s installation at the Hammer incorporates this video, a textile on the floor, a television screen, and a clay speaker, all of which are connected through copper wires. The clay speaker, used in a previous project titled Figures of Speech at SculptureCenter in New York, signals the artist’s ongoing preoccupation with sound and the problem of voice. It is also a material signifier of conduction and the abstraction of sound from the body through material. Hear, Here, a project at the New Museum in New York in 2014, was a gallery exhibition, workshop, and experimental opera during which the performers deployed the sculptural props in the gallery. “Centering on a paradoxical landscape—a mountain that is also a cave—the exhibition and its constantly shifting elements (including musical instruments, staging tools, and performance artifacts) produce a reactive space that focuses on the politics of vocalizing perspectives and the necessity of participation in lived experience.”5 Here again the clay speaker, the Matter-phone (2016), is seen in production during the video; typical of Oleson’s work, it engages and holds in tension several sensory entry points at once.

The centerpiece in the gallery is an abstract textile: a digitally designed and handmade rug. The grid that structures the flat composition is based on the “platter” or ground that orients virtual objects in 3D imaging programs. It compresses and expands in ways that reference perspective and the history of not only modernist abstract painting but also women artists such as Anni Albers, whose Bauhaus textiles functioned as objects and as labor that crossed over from the realm of the domestic to that of fine art. Oleson updates these ideas by using digital technology to generate form, insisting on the haptic object and the sensory experience in the gallery.

—Connie Butler

Notes

1. Karen Barad, “Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter,” Signs, 28, no. 3 (Spring 2003): 812.

2. https://jeanineoleson.com.

3. The artist described the project in a presentation for Creative Capital, an organization that funds artistic research and production and supported this project. See https://youtu.be/O23gI6Lqzus.

4. From correspondence with the artist, April 19, 2017.

5. Visit the project website at http://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/view/

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.

The Hammer Museum's Artist Residency Program is supported by The Kayne Family Foundation and Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Jeanine Oleson’s A Human(e) Matter is a project of Creative Capital, with additional in-kind support from Diane and Michael Silver.