Dr. Pozzi Comes Home

Last Friday, October 3, the Armand Hammer Collection reopened in galleries newly designed to show off the museum’s impressive array of old master and 19th Century paintings, drawings, and sculpture. The product of months of careful planning by curator Cynthia Burlingham, exhibition designer Peter Gould, and colorist Scott Flax, along with a dedicated team of Hammer staff, the new installation situates this diverse selection of works within galleries that seamlessly combine contemporary and historical elements. Within two expansive rooms, traditional architectural details like wainscoting and crown molding are updated thanks to a sophisticated, linear profile. Painted custom-designed shades of golden wheat and antique parchment, the subtle shift in hue between the two rooms evokes the diurnal transition between the bright light of day and the muted luminescence of evening. With an overall color scheme thoughtfully keyed to the yellows, peaches, and umber pigments composing the works themselves, the paintings on view appear to glow from within.

One of the most impressive works on display is Dr. Pozzi at Home, John Singer Sargent’s 1881 portrait of Samuel Jean Pozzi. Standing in his scarlet dressing gown with characteristic panache, the Parisian gynecologist appears quite at home (pun intended) in his newly-designed apartments here at the Hammer. Pozzi, a close friend of Sargent and a renowned dandy, was described by a contemporary as “himself a kind of beautiful work of art.” Swaddled in a plush robe with crisp ruffles peeking out from the collar and sleeve, shod with embroidered slippers, and flanked by a velvet curtain, Pozzi boasts all the grandeur of a Renaissance prince combined with the casual élan of a turn-of-the-century aesthete.

One of the most notable aspects of the portrait are the figure’s hands. Elegantly attenuated fingers grasp the collar of his robe and pull demurely against the tie around his hip. Along with the face and neck, they are the only exposed areas on Pozzi’s body, a distinction which makes them appear precious. It has been suggested that the emphasis on the hands may be a reminder of Pozzi’s trademark examination method that involved manual exploration of his female patients’ anatomies. More recently, the art historian Alison Syme has read the delicacy of Sargent’s painted hands as ciphers of homoerotic desire. Certainly, the sumptuousness of this painting in particular lends it an erotic charge.

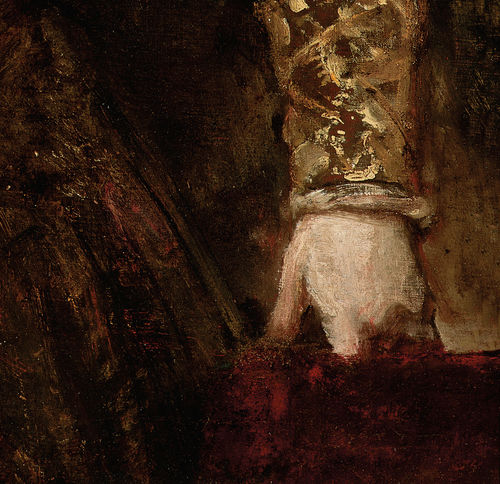

As a frequent observer of the Armand Hammer Collection, I cannot help but notice the similarity between the manner in which Sargent has depicted Pozzi’s hands and that of another work in our collection – Rembrandt’s Juno. In both works, the hands closest to the hip are the most spontaneous and painterly of appendages, appearing as so many visible brush strokes rather flesh-covered bone. It is unlikely that Sargent was familiar with Rembrandt’s Juno in particular, which by the late 19th century was in a private collection in Berlin, though Sargent would have certainly known other works by Rembrandt, whose reputation as a bohemian, outsider genius grew steadily throughout the period. It seems that for both Sargent and Rembrandt, the hands are the tell-tale detail. They are the passage in which the painter’s artifice gives way to the reality of the material he wields. They call attention to the work of the artist’s own hand, and through this comparison between painted hands and painting hand, the artist’s prodigious skill is at once suspended and revealed.

I am not the only person to notice the elegance of these hands, of course. Before Pozzi went on hiatus, a visitor to the museum declared, “The hand on this Sargent is one of the more beautiful things I’ve seen in a while.” Resplendent against the chamois walls of the new galleries, Pozzi is joined by several more “beautiful works of art” from the Armand Hammer Collection. To quote another visitor: “Welcome back! The Hammer Museum is whole again!”