Good Fences

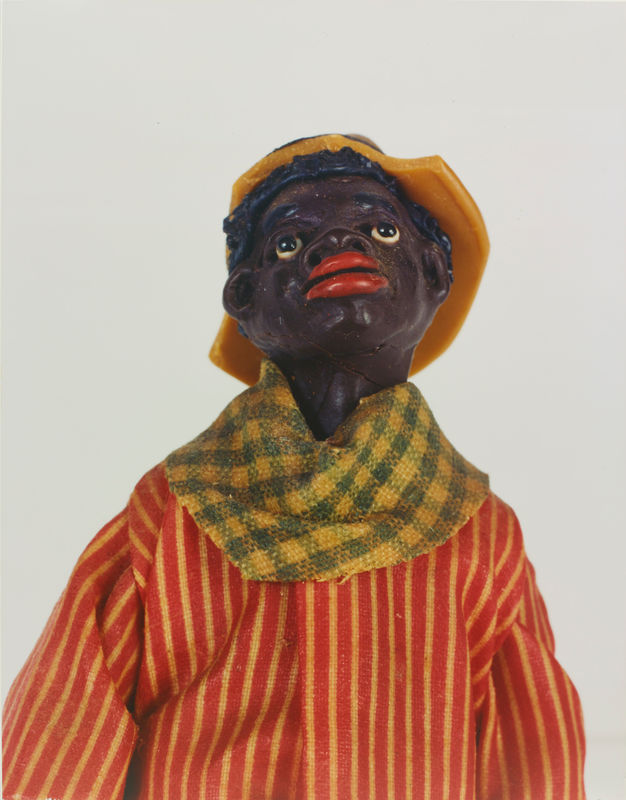

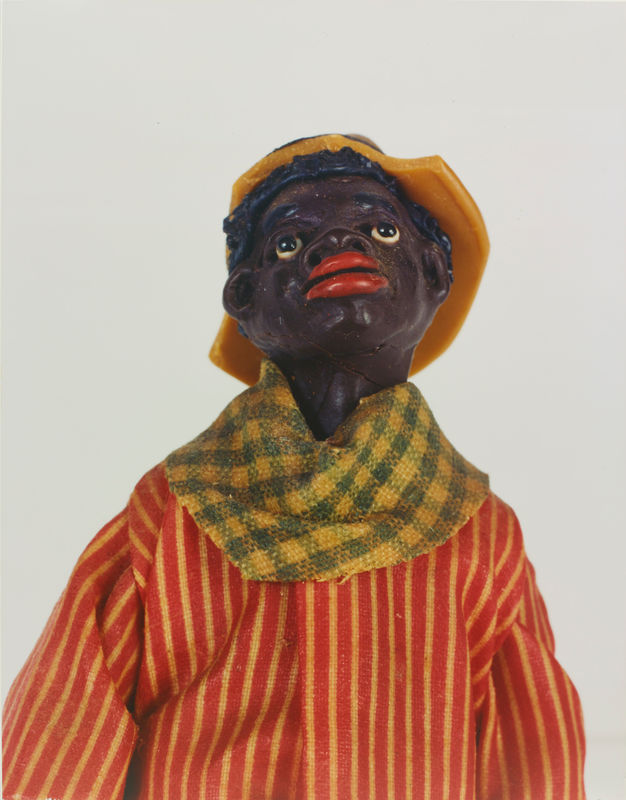

What has been done here? In five large-format color photographs printed in 1995, Fred Wilson has depicted blackface figurines, which rarely stand more than a few inches high, as though they are human portrait subjects. Severely framed and cropped just so, they take on a presence that is markedly more corporeal than it is thing-like. By deploying this scale, Wilson presents a construction that at once summons and amplifies the familiar intimacy of the portrait session. Through his own regard for his subjects, Wilson recovers a modicum of integrity for the racist commodity's human referent. This operation of Wilson's approximates recognition in the Arendtian sense#—but the artist also indicates his awareness that the situation he himself shares with that referent is anything but resolved. In one instance, he took an image of a ceramic mammy figure with an S (for salt) printed on the belly and added the letters hit to the photograph as a kind of watermark. He imposes a modern understanding on this historically complex phenomenon but does so with a device that openly signals his role as the author of the resultant image. "Shit" may or may not tell us how certain members of this object's commissioning culture really felt about mammy. Now it alludes to the hostility toward black Americans that this entire object class continues to exert. Wilson's appropriation makes the old new to stop us forgetting the character of the past that follows in our train.

And here? To tell his Backyard Story (1997), Haim Steinbach has fitted to the back wall of a metropolitan art gallery a steel and particleboard shelving unit better suited to the basement or garage of a home located well outside the city. The shelves frame a collection of accoutrements of autumn: jeans and T-shirts hung from a clothesline, decorative jack-o'-lanterns, firewood, charcoal grills. In its original setting, Steinbach's array—identical objects displayed in groups of four, with each type occupying one quadrant of the grid—sat flush against the gallery wall, as though borrowing its posture. That rigidity anchors the work's irony: down to its slightly bowing particleboard shelves, Backyard Story comprises elements, all of them objects but not of the sort that art galleries typically showcase. One feels sure that Steinbach chose these for their mereness, transience, and gross multiplicity. Like all the seasons, these vivid, vernacular emblems of fall are about their changes, which their form and their diffusion across contexts both reflect. Though wholly made up of things whose use deforms them, the work also makes transparent the perpetual unity of symbol, symbology, and structure. In order to be so legible as critique, Steinbach's construction literally leans on the art system's very differently determined economy of change, its differently cycled temporality, its conception of the thing as irretrievably bound to exiguity.

And how about here? Onto a canvas covered with an uneven preparation of gesso and white oil paint, Sue Williams has grafted in black acrylic a palimpsest of six cartoons from "men's entertainment" magazines. You're probably doing something right if you don't know the type of cartoon that I mean: here, a lecherous doctor assaults a busty, headless female patient in the course of a physical examination; there, a man holds a gun to his wife's head to get her to engage in intercourse with him. Williams decouples this imagery from the brazenly misogynistic captions on which it customarily depends. Her redaction demonstrates in a strikingly economical and smart way the captions' redundancy given the imagery's openly violent nature. The lower fifth of Williams's composition is a separate panel altogether. It includes some dialogue from Richard Prince's notorious joke paintings. À la Warhol, it appears doubly registered, emphatically citational, and somewhat hard to read. This one portrays a man rendered impotent by his own failed attempts at humor. In this way, Williams's construction reconciles two fragments of the culture imagined to be starkly opposed: systematic misogynistic violence and the postmodernist critique of popular representations of the drives. By conjoining them, Spiritual America (1992) enlarges our view of troubling correlations between unchecked practices of sexism and halting efforts to interrogate the sexual politics of painting. By her choice of a grossly popular source, Williams signals how well we all know that the medical and marital institutions give excellent cover, even camouflage, to exploitations of the most violent sort. But by tucking her borrowings into a painting, she underscores the medium's implication in these practices: every bit as much as doctors and husbands, many painters themselves constitute an institution ripe for critique.

When dealing with this art, a certain condition still prevails upon us to start out from classificatory constructs assuming that its fabrication and concrete materials were determined by an overt motive or abiding need to use this to do something to some other thing. I am hardly concerned to suggest that this wasn't very often the case or that it shouldn't have been. But I do wonder how else forceful critique, or statements about and against power, comes about in the realm of this art. The preceding accounts of three items chosen from the working checklist for Take It or Leave It exercise some speculation about a kind of description that foregrounds the materiality of such a motivation—by this I mean the actuality of artists' efforts to make objects issue complaints originating in subjective experience. To demand that an image or thing convey people problems—that's a lot to ask of an image or thing. Thanks to this general thrust of normative accounts of appropriation and institutional critique, to invoke either is tantamount to saying, "Get ready for some of the most intentional art ever!" While in such a situation it can be difficult to just look, when one does, one tends to see a great deal more than these hyperintentional rubrics tend to highlight. One wants to insist, for instance, that it matters in as-yet-unreckoned ways that the works over which I lingered above are not first and foremost installations but, respectively, a photograph, a sculpture, and a painting. But in such an insistence, the hope is simply to put into some perspective the generalizing, the reading exclusively for emphasis, that so often sets the mood for discussions of this art.

We could tell the stories of these practices in another way—say, by proposing a genealogy of appropriation and institutional critique that also writes the history of a shift in the valences of form construction. But such a history would need to leave a lot of room for aspects, even criteria, of art that the critique of institutions often seems quite eager to set aside. Another, utterly defining element of what Wilson, Steinbach, and Williams had to do to create these works was the notably unfussy, differently intentional act of putting stuff together. You take something and set it next to something else in order to pose, but not necessarily to answer, a question about their relationship. You do this not because on its own it's a particularly interesting thing to do but because, as a context, art gives things-in-relation a capacity to inform that no other framework can. What becomes of analysis and interpretation when description, without which neither can proceed very far, foregrounds the relationship—the condition of besideness—that is the sine qua non of critique made manifest as art?

Take It or Leave It's project to investigate the relationship between appropriation and institutional critique in work by artists who came to prominence between the late 1970s and the early 1990s is long overdue and utterly salutary. It has taken a surprisingly long time for someone to recognize how fruitfully these separate categories, and particularly the specific creative originality of the production channeled into them, have continually informed and troubled each other, and often from very distant positions on art history's time horizon. The question why is of utmost importance to the historiography of recent art, and as an assembly, the present exhibition models it with a searing intelligence. But these categories have always shared something, which is allowing very little finesse where it concerns close consideration of the works they would claim. Ten years of teaching recent American art and its attendant contexts and theories have familiarized me with the rather astonishing power of the terms appropriation and institutional critique. They arrive like heavy weather on the scene of interpretation, in part because they're tethered to historical and sociopolitical circumstances—variously charged, these include the unchecked suppression of complexity in representations of popular life and the astonishing incapacity of established institutional powers to accommodate new cultural arrangements—that we experience as intensely real. For this reason they tend to make shockingly quick work of coming to terms with very complex art, which should be difficult and at least a little bit slow. What specific artistic and theoretical operations do appropriation and institutional critique want to claim? Which would they disavow?

Excerpted from Take It or Leave It: Institution, Image, Ideology. Copyright © 2014 by the Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center, Inc. Published by DelMonico Books, an imprint of Prestel. The full essay can be found in the exhibition catalogue, available here.

See Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958).