Robert Gober

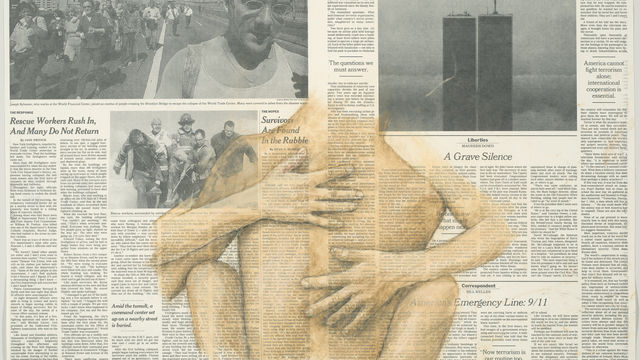

The work of Robert Gober frequently mines ordinary images and objects for their associations with larger social and political contexts, transforming them into distorted and even surreal markers of everyday experience. Through his eerie treatment of familiar objects—like body parts, sinks and cribs, a silk wedding dress, and patterned wallpaper—Gober evokes what feel like buried memories, creating scenes of domestic rituals gone awry. These works investigate the complicated and often subliminal ways in which cultural identity can be conveyed through objects. Gober is skilled at bringing together the apparently irreconcilable; it is not uncommon for one of his works to be described simultaneously as funny, perverse, haunting, confounding, and sad. Indeed, as soon as a comprehensive understanding of a piece seems within reach, some contradictory angle elbows in to destabilize it again.

Uneasy juxtapositions are also the crux of Gober’s Hanging Man / Sleeping Man (1989) wallpaper, which is made up of a pattern of a two-part illustration: a black man hanging, lynched, from a tree branch, and a white man soundly asleep beneath the covers. From afar, the repetition takes the imagery out of the particular and into the realm of decoration, a pattern placed on the surface of a domestic space. But a closer vantage reveals that the images are particular and very disturbing. That the white man appears to sleep peacefully in close proximity to heinous violence underscores the central role race plays in providing (or denying) a sense of security and safety in American life. In certain configurations, he seems even to be dreaming of the image of the hanged black man. The wallpaper reworks the history of dispossession on which America is built into domestic decoration. Given that institutionalized violence and racism remain pervasive today, the wallpaper also seems accusatory: is it not we who sleep on?

—Leora Morinis