Louise Lawler

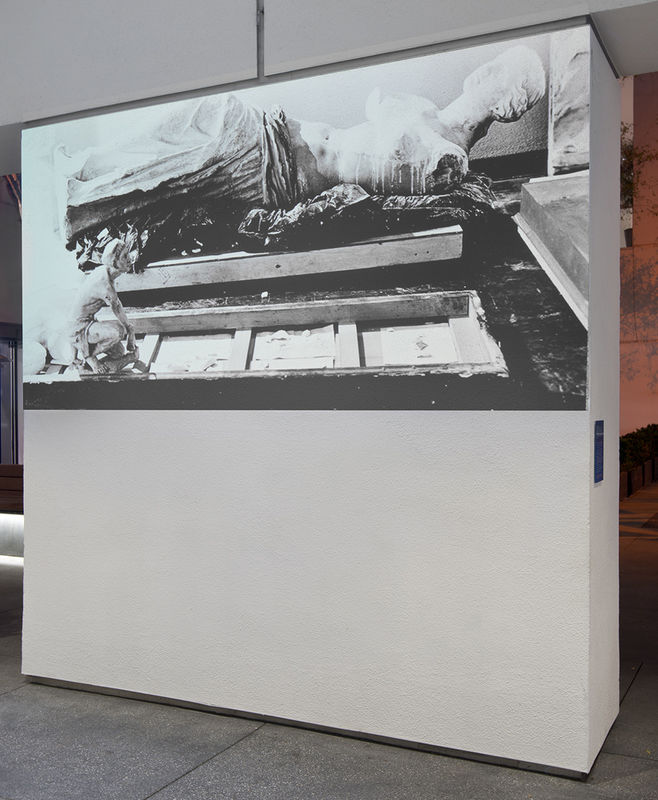

In her photographs, installations, and objects, Louise Lawler executes a critique of art-world systems that is at once straightforward and subtle, rigorous and humorous. She is widely known for photographing various sites related to the distribution of art, such as art galleries, auction houses, private collections, and museums. Works by other artists have provided the subject matter for a number of works, including her color photographs Bulbs (2005–6) and No Drones (2010–11). In Bulbs, strings of lightbulbs laid out on packing blankets bisect the composition. The bright yet muted lighting and soft focus in the foreground soften the institutional surroundings and project a warmth that seems unusual for the subject until it becomes clear that these bulbs are actually a sculpture by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, a friend and colleague of Lawler who died from AIDS-related complications in 1996. Awaiting installation, the sculpture lies cold and mute on the tables. Lawler's unusual perspective—roughly at eye level with the lifeless sculpture—creates a composition that recalls a seascape with an endless horizon. No Drones pictures Mustang-Staffel (Mustang Squadron), a 1964 painting by the German artist Gerhard Richter that depicts a group of Mustang bombers, the planes that were used by Allied forces to help defeat the Nazis in World War II. Lawler photographed the painting at an oblique angle so that we see the hanging device attached to the stretcher bars behind the canvas. The title of the work is both a literalism (there were no drones during World War II) and a call to end the production and use of airborne instruments of war.

Alongside her work in photography, Lawler has deployed various other mediums throughout her career. From screening the legendary film The Misfits (1961) without the picture in A Movie Will Be Shown without the Picture (1979) to installing works by other artists in a new configuration for her Arrangements of Pictures (1982), Lawler uses conceptual strategies and intentionally contrived installations to expand her engagement with her subjects and to further question the systems that govern art as well as its display and consumption. For the audio work Birdcalls (1972–81), she sounded out the names of various well-known male artists—including Vito Acconci, Carl Andre, and Donald Judd—in the style of birdcalls. Birdcalls is a witty rejoinder to the perceived earnestness that is associated with many of the artists named, acknowledging their mantle while also poking fun at their plumage. Its humor is balanced by the knowledge that these white male artists are continually recognized as being at the forefront of serious art production, leaving little room for consideration of the significant contributions of female artists and artists of color to the discussion of advanced aesthetics.

—Corrina Peipon