Andrea Fraser

Andrea Fraser makes work that addresses its own social, ideological, psychological, and political parameters as well as the conditions of the institutions in which it is presented. She is known for her biting and often very funny versions of various art-world fixtures: gallery talks, wall texts, welcome speeches. In her performance and video works, she often takes on personae that function both as character studies and as critical investigations of the sites for art, revealing the layers of context and construction (of class, gender, politics, etc.) that ground their very existence.

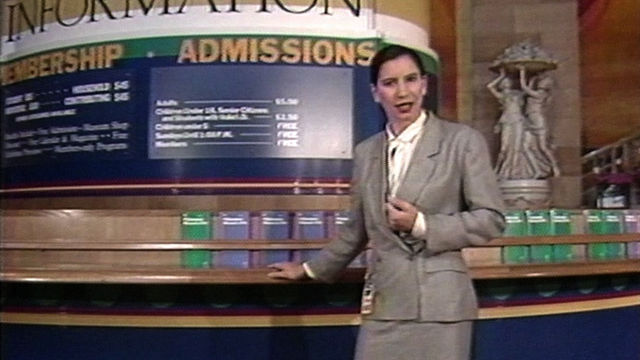

Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk (1989), one of Fraser's most acclaimed works, borrows the form and conventions of a museum tour. She plays the role of "Jane Castleton," a fictional museum guide who—in a gray suit and white button-down shirt, with hair pulled back—is at once priggish and unhinged. Fraser has a preternatural ear for the particularities of speech, and initially her tone and demeanor are what one might expect of a museum tour guide. But as she enthusiastically leads visitors around the Philadelphia Museum of Art, her language spins out into a kind of fevered pastiche. Though words roll off Castleton's tongue, there is a disjointedness to her parlance, stemming from the fact that Fraser's script includes direct quotations from a variety of sources, including brochures from the museum's archives, art reviews, Immanuel Kant's Critique of Judgment, and Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan's 1969 anthology of essays, On Understanding Poverty.#

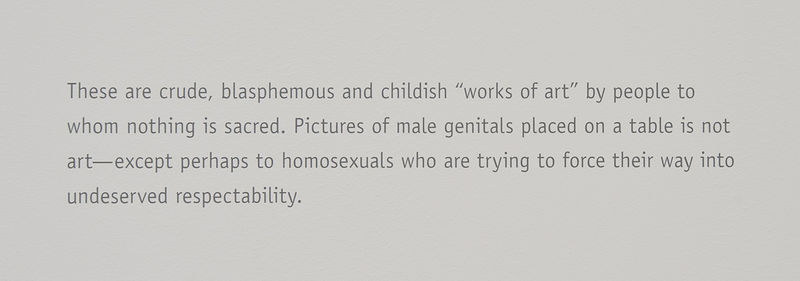

The tour reaches beyond customary boundaries in other ways too: Castleton discusses funding and sponsorship and leads her unwitting group to the museum's interstices: the bathrooms, the cafeteria, the water fountain (which she praises, with a manic gleam in her eye, for its "formal economy" and "monumentality"). She is as enamored of the walls and fixtures of the institutional infrastructure as of the art it houses, her excitement out of whack with the mundane objects to which she points. Castleton's display of affective attachment to the museum makes for an entertaining and screwball character, but Fraser's video also asks whether the pressures placed on art—the superlative claims and displaced desires—are similarly disproportionate. Museum Highlights draws attention to serious questions about the role of the museum in the civic landscape: its pedagogy, aesthetic criteria, and systems of judgment.

Language, power, and performance have remained central to Fraser's practice, and in a later work, Official Welcome (2001–3), she examines a different category of artspeak: the introductory and acceptance speeches at exhibition openings and award ceremonies. Fraser assumes in quick succession the roles of sixteen art-world archetypes—thoroughly researched and scripted—and the speeches are canny in their precision. The introducers pontificate effusively about the power of these artists to, for example, "propose utopian visions," "make space for radical criticality," and "create objects of unfathomable beauty." The artists themselves speak in various voices, some with a put-on modesty if not a kind of indifference and others with pomposity or disdain for those who would honor them. When one character, a downtrodden postfeminist, strips down to Gucci underwear and heels, her self-reflexivity and droll wit remain impressive: "I'm not a person today; I'm an object in an artwork. . . . It's about emptiness." By single-handedly adopting one posture after another, Fraser makes visible the seams and pretense of these positions and the ubiquity of these types of speeches in the art world. Here professed humility can be seen as a front for grandiosity, revealing the self-congratulatory circuit of the art world. But what can feel in some instances like self-conscious posturing is also shown, in her embodied performance, to be the genuine sentiments and vulnerable emotions of figures deeply invested in their work and the rituals intended to honor achievement. Official Welcome masterfully balances these clashing affects of cynicism and gratitude.

—Leora Morinis