Rebellion and Its Aftermath

Decades of pervasive and systemic racial discrimination and isolation in Los Angeles erupted in 1965 with the Watts rebellion—the largest U.S. urban uprising of its time. The six days of civil unrest stunned the entire country, not only because it was the most destructive racial explosion since the Detroit riots of 1943 but also because it took place in socially progressive Los Angeles, still perceived by many as a relatively favorable city for African Americans. As art historian Cécile Whiting notes, "The racial upheaval in the Watts district of the city in August 1965 further challenged the myth of the Angeleno good life by exposing tensions between police, city officials, and African American residents of Watts; the racial disparities in the city were suddenly national news."# The violence in Watts shattered popular myth and forced white Los Angeles to publicly face the long history of racial inequality in the city.

For many African American artists in the 1960s and 1970s, the events in Watts represented a poignant statement about the volatile reality of race relations during that era.# Racism and discrimination in education, employment, and housing were an undeniable reality, and in the wake of the rebellion, artists in Los Angeles began to reconsider the political and social potential of their work and to look for ways to represent the crises facing their city and communities. Among the important practices that artists generated in the rebellion's aftermath, assemblage and film were especially significant. And even though the resulting bodies of work are rooted firmly in the particular context of Los Angeles, they are at the same time connected to an international aesthetic discourse, specifically to work produced concurrently by black artists in Great Britain. In both London and Los Angeles, social turmoil forced black artists to search out new means for expressing the realities of their respective experiences—to aesthetically redress conflict and destruction through artistic forms that bring together fragments from the communities around them.

The uprising in Los Angeles led artists to consider the transformative power of art, which was realized in the reworking, quite literally, of the physical ruins of South Los Angeles. As artists crafted works out of the charred remnants of their world, a form of assemblage art was born. Mixed-media assemblage, or the use of actual objects to construct works of art from component parts, became key in articulating the desire to develop new and more complex means to understand and comment upon society. The resulting movement was by no means monolithic, however; rather, artists developed a multitude of ideas about the artistic potential of assemblage. For Noah Purifoy, discarded objects were democratic: they didn't discriminate against those who could not afford or access "fine" art materials. For John Riddle, assemblage was a clear metaphor for the process of change required of art to "advance social consciousness and promote black development."# As John Outterbridge noted, "What is available to you is not mere material but the material and the essence of the political climate, the material in the debris of social issues. At times even the trauma within the community becomes the debris that artists manipulate and that manipulates the sensibility of artists."# Assemblage therefore became an important artistic strategy that not only radically changed notions of art and art making but also offered a medium through which the artist was able to redefine the relationship between viewer and object, and between artist and social context. The artist's choice and manipulation of reality itself became the subject of new work. It was as if artists were calling into question their own relationship to the times and the all-encompassing history of the moment in which their work would be seen.

Many black artists in Los Angeles mobilized the medium of assemblage as a way to comment on the role of the artist as a social agent. For Outterbridge, art with social commentary evolved naturally from the climate of the times—he came to think of himself as an "activist-artist" whose "studio was everywhere."# Outterbridge's interest in discarded materials, however, started from a young age. His father ran a business in segregated Greenville, North Carolina, collecting and recycling metal machine parts and farm equipment. The artist also credits his grandmother for inspiring him with the handcrafted necklaces and beaded pouches (asafetida bags) she used in her healing practice. For Outterbridge, artifacts made by healers to ward off ailments and ill will possess a curative and transformative aesthetic power that he aspires to deliver in his own work.# Drawing inspiration from Dada, folk art, and African sculpture, Outterbridge translates discarded materials into poetic configurations that explore both social and political themes. Objects in his Containment Series—such as Eastside-Westside (c. 1970)—were constructed from cut and flattened tin cans with charred wood and rusted nails brought together in ways that avoided stereotypical markers of African American identity and were topically loaded without being overtly polemical. By manipulating found materials, Outterbridge excavates personal and cultural histories that have been covered over, neglected, and hidden.

In Great Britain, uprisings, police brutality, and housing inequality led black artists there to embrace this very same understanding of the artist's role as well as the potential of assemblage in producing artwork that reflected the era's political and ideological tensions. Race riots in London's neighborhood of Notting Hill in 1958 and another in 1976 at the conclusion of the Notting Hill Carnival resulted in the injury of more than one hundred police officers and residents. Disillusioned and angered by increasingly hard-line policing strategies, black Britons began developing a growing politics to address racial intolerance. By the late 1960s and well into the 1980s, artists began using documentary film in a manner similar to that of assemblage, appropriating fragments of real life to express the strife and rebellion in their communities. There were multimedia works as well, such as Keith Piper's Another Nigger Died Today (1982).

Trinidadian-born Horace Ové's Pressure (1975) explores the assimilation of Caribbean people into British society. Hailed as Britain's first black feature film, Pressure is a hard-hitting, honest document of the plight of disenchanted British-born black youths. Set in 1970s London, it tells the story of Tony, a bright high school dropout, the son of West Indian immigrants, who finds himself torn between his parents' churchgoing conformity and his brother's Black Power militancy. As his initially high hopes for life are repeatedly dashed—he cannot find work anywhere; potential employers treat him with suspicion because of his color—his sense of alienation grows. In a bid to find a sense of belonging, he joins his black friends who, estranged from their submissive parents, seek a sense of purpose in the streets and in chases with the police. Shot in a gritty realist style, with an often documentary feel, the film traces a black teenager's attempts to deal with the cycle of educational deprivation, poverty, unemployment, and antisocial behavior in London. The film also spotlights police harassment and the controversial "sus" (suspicion) laws as well as the media's underreporting and misrepresentation of black issues and protests. Ové convincingly captures the spirit of the 1970s, a pivotal period for race relations in Britain and the politicization of a generation, while also acknowledging the influence of African American political leaders of the 1960s and 1970s such as Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael.#

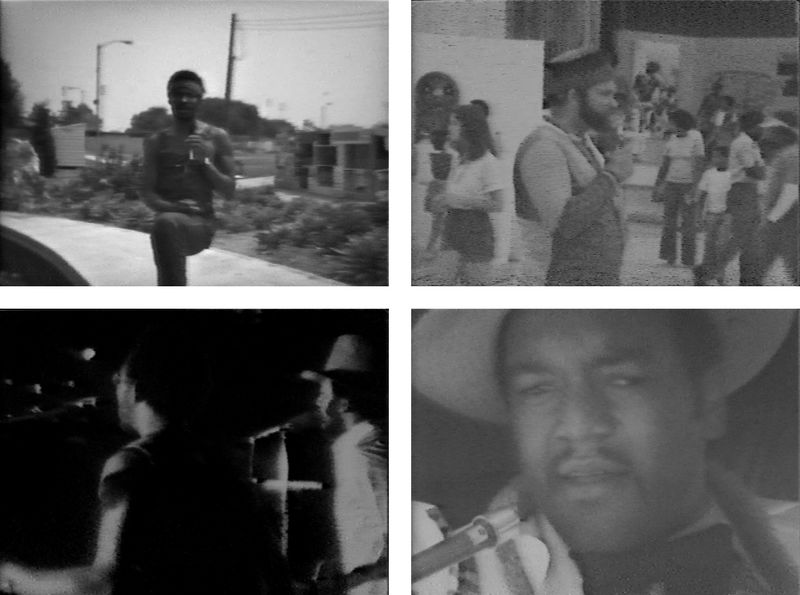

In Los Angeles in the early 1970s, Ulysses Jenkins formed the media group Video Venice News, devoted to shooting documentary work in Southern California. One of his early videos, Remnants of the Watts Festival (1972–73, compiled 1980), is an important record of this historic community event commemorating the Watts rebellion of 1965. Shot in a documentary style similar to Ové's, the film features, among other things, an interview with "community curator" Cecil Fergerson and a walkthrough of the festival with Black Arts Council cofounder Claude Booker. In 1966, during the summer following the rebellion, the first Watts Summer Festival took place at Will Rogers Park on 103rd Street. Planned as an annual summer event, the festival did more than memorialize the lives lost in a fractious chapter of the city's history; it also celebrated Los Angeles's cultural diversity and the ideal of a black cultural renaissance emerging from the ashes of the uprising. In filming the festivals of the early 1970s, Jenkins aimed not only to portray Watts as a place for the peaceful gathering of humanity but also to counter the pervasive negative press the neighborhood had received in the years following the uprising. The film also examines the issue of covert surveillance, which, many believe, emerged after the rebellion and continues to this day to define the relationship between the state and the African American community. Jenkins puts forward that the upsurge in police surveillance during these years served to reinforce destructive stereotypes, pervasive in the mainstream media, that African Americans in Watts were dangerous. For Jenkins, a film such as Remnants of the Watts Festival was needed to "correct the negative images of Blacks in conventional media outlets."#

In both Los Angeles and London, rebellion and its aftermath produced a commonality of experiences that acted as a catalyst for an artist to make art. Social unrest, followed by destruction and trauma, required the development of a new visual language, one capable of imaginatively redrawing the discursive contours of a society as yet unreconciled to the changes in its internal dynamics produced by its diasporic communities. In London this language was brought forth by young African, Caribbean, and Asian artists coming into view in the early 1980s, among them the film collectives Black Audio, ReTake, Ceddo, and Sankofa, all of which were encouraged, in 1982, by the debut of British television's Channel Four along with the ACCT Workshop Declaration, which supported experimental media. From these groups emerged artists such as John Akomfrah, Isaac Julien, Martina Attille, and Lina Gopaul, whose work would address racial and social politics in Britain during the Thatcher era.

Black Audio's Handsworth Songs (1986; dir. John Akomfrah) is a documentary-type film essay on race and disorder in Britain. It looks at the historical, social, and political backdrop of that country's racial unrest and at the anger and disillusionment felt by many from the ethnic communities in Britain. It was filmed in Handsworth and London during the riots of 1985, and uses extensive newsreel and archival material, ranging from shots of colonial labor to images of Caribbean and Asian settlement. Reflecting on the format of the film, collective member Reece Auguiste has stated, "Our task was to find a structure and a form which would allow us the space to deconstruct the hegemonic voices of British television newsreels. That was absolutely crucial if we were to succeed in articulating those spatial and temporal states of belonging and displacement differently. In order to bring emotions, uncertainties and anxieties alive we had to poeticize that which was captured through the lenses of the BBC and other newsreel units—by poetizing every image we were able to succeed in recasting the binary oppositions between myth and history, imagination and experimental states of occasional violence."#

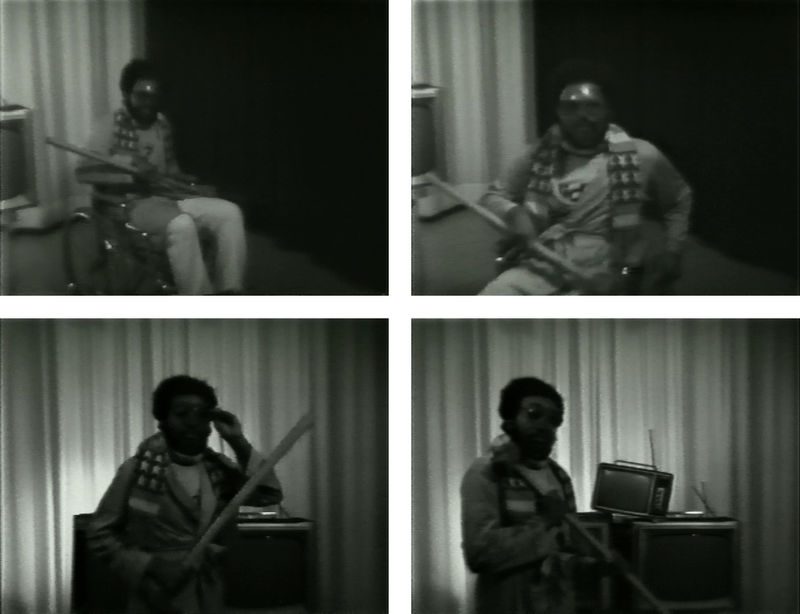

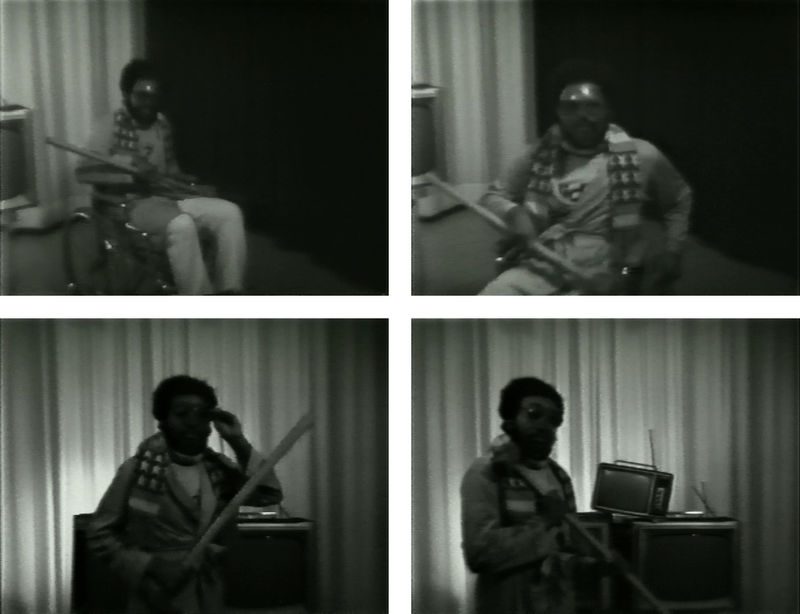

Los Angeles artists likewise referenced mediated images as a means to critique the discursive and physical violence of mainstream representation. Betye Saar's mixed-media sculpture Imitation of Life (1975) is an example of how black artists reconfigured images from popular culture in order to expose the latent truths such stereotypical images attempt to mask. Jenkins's four-minute video Mass of Images (1978) integrated performance art to explore various stereotypes in media history that have reflected and reinforced deeper patterns of historical racism in the United States. Appearing masked throughout the film, Jenkins performs a mantra that speaks to his disdain for the stereotypes of African Americans that were pervasive at the time. Later, viewers see Jenkins in a wheelchair—suggestive of the crippling effect these images have had on the artist and on the black community at large. The film concludes with Jenkins using a sledgehammer to demolish several television sets behind him. Despite his efforts to destroy these images, literally and figuratively, Jenkins realizes that ultimately he can do nothing to change the way the mass media portrays African Americans.

Through assemblage and film, black artists in Los Angeles and London used their work not only to react to and comment upon a period of intense social and political change in their respective cities but also to participate in subjective investigations of the relationship between life and art. Although the ways in which race was understood may have been different between the two cities, in both cases artists turned to assemblage and film to work through such social constructs aesthetically, recycling society's discards to produce defiant configurations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This essay owes much to the generosity of many people, including Kellie Jones, Douglas Fogle, Brooke Hodge, and especially Tobias Wofford. I also thank my mom, Joy Simmons, for teaching me to love art and to value those who create it.

Cécile Whiting, "Los Angeles in the 1960s," in Time & Place: Los Angeles 1957–1968, ed. Lars Nittve (Stockholm: Moderna Museet; Göttingen: Steidl, 2008), 12.

John McWhorter, "Burned, Baby, Burned: Watts and the Tragedy of Black America," Washington Post, August 14, 2005, www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/08/13/AR2005081300103.html.

John Riddle, interview by Karen Anne Mason, September 5, 1992, African American Artists of Los Angeles, Oral History Program, University of California, Los Angeles, transcript, p. 123, Charles E. Young Research Library, Department of Special Collections, UCLA.

John Outterbridge, interview by Richard Candida Smith, April 30, 1990, African American Artists of Los Angeles, Oral History Program, University of California, Los Angeles, transcript, p. 362, Charles E. Young Research Library, Department of Special Collections, UCLA.

Ibid., p. 243.

Lizetta Lefalle-Collins, "Keeper of Traditions," in John Outterbridge: A Retrospective (Los Angeles: California African American Museum, 1994), 7.

Kim Janssen, "Horace's Life in Black Power," New Journal Enterprises, July 1, 2005, www.camdennewjournal.co.uk/063005/f063005_02.htm.

Paul Von Blum, "Ulysses Jenkins: A Griot for the Electronic Age," Journal of Pan African Studies 3, no. 2 (September 2009): 139.

Reece Auguiste, "Handsworth Songs: Some Background Notes," in The Ghosts of Songs: The Film Art of the Black Audio Film Collective 1982–1998, ed. Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007), 157.