Now Dig This!

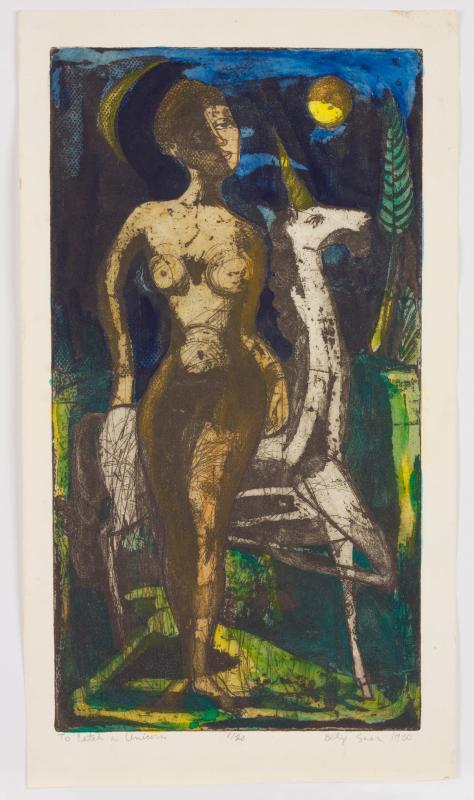

In 1960 Betye Saar created To Catch a Unicorn. It is among her first prints, and in it she lays out a hint of the imagery she would mine for years to come. Both the sun and the moon, elements of the cosmos, hover over a dark sky. They shine above a forest scene in which we see a woman grasping a unicorn; both tilt their heads skyward. In Western mythology, the unicorn is seen as a force for good, though wild and able to be tamed only by a virginal maiden. Against the unicorn's traditional whiteness, the virgin is shapely, nude, black.

To Catch a Unicorn is emblematic of Saar's emergence as a fine artist and her early exploration of print technique. It is, furthermore, an allegory and assertion of a changing cultural landscape. The rising strength of the black community in Los Angeles was representative of the new political, social, and economic power of African Americans across the nation in the period from 1960 to 1980. Like Saar's figure, a growing black majority laid hold to the mystical utopia that Los Angeles symbolized for many Americans. This body worked to tame institutional discrimination, white repression, and racism through the collective power of civil rights and Black Power activism. In the process, it changed the sense of what constituted African American identity and American culture.

The new strength of African American communities in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s was part of the increasing radical activism in ethnic communities and in the feminist, youth, and antiwar movements throughout the United States and all over the world. Yet we can also ascribe this social energy to changing demographics as the number of black citizens migrating to California rose during the twentieth century, creating growing majorities in places such as Los Angeles. These new city users (as scholar Saskia Sassen calls them), fleeing old lives, laid fresh claims to the possibilities of democratic change and social freedoms. For many of the artists in Now Dig This!, migration to Los Angeles presented the opportunity to find a livelihood as a creative person. Some had been born in the South, among them Purifoy, Lewis, and Edwards. Others, including William Pajaud and Outterbridge, headed first to the black cultural capital of Chicago before making their move West. The possibilities and power that this western environment signified also became the substance of their art.

FRONTRUNNERS

Los Angeles began coming into its own as a cultural capital in the late 1950s with a rise in gallery activity and art patronage. By the early 1960s it was recognized as the second center of American art, after New York. Artists such as Betye Saar, Melvin Edwards, Charles White, and William Pajaud were part of a generation that willed an African American art community into existence with little traditional art-world support. They mounted exhibitions in homes, community centers, churches, and black-owned businesses. Some initially continued to work commercially while pursuing fine arts; Pajaud, for example, sold watercolor paintings to local department stores. The early careers of these frontrunners bring us into the 1960s and cut a path for the emergence of a cadre of professional artists. Their examples and mentorship were a catalytic force in creating and helping to sustain a vibrant black arts scene in the city.

Saar, a Los Angeles native, began her career as a designer of graphics, interiors, and jewelry. By 1963 she was a young mother with three children but intent on becoming a fine artist. Works on paper and the duplication and experimentation possibilities of the print format allowed her technological innovation while also being manageable creative forms. In the color etching To Catch a Unicorn, the themes of alternative spiritual practices and cosmologies as well as the centralization of a female protagonist foreshadow their importance in her later assemblages.

Edwards arrived in Los Angeles from Texas in 1955 to pursue his college degree, a path indicative of the increased presence at midcentury of African Americans in BFA and MFA programs, fueled by disintegrating barriers to both de jure and de facto segregation. By 1967 Edwards had become one of the city's most visible African American artists, capturing numerous awards and participating in several high-profile shows, including a solo exhibition at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. He began experimenting with mixed-media relief and welding in 1960, producing the first sculpture in his Lynch Fragment series, Some Bright Morning (1963). The series contextualizes the police brutality that was rampant in the city within a larger American history of violence against African Americans of which lynching was emblematic. The sculptures are made of industrial remains—locks, chains, tools, gears—but do not carry the same ephemeral quality that characterizes the more visible assemblage constructions in California at the time. Edwards expanded his compact gestures in steel in larger pieces such as August the Squared Fire (1965), a meditation on the Watts rebellion of that year.

Edwards and poet Jayne Cortez were part of the same artistic circles in Los Angeles. Cortez had been raised in Watts, and at eighteen she married jazz innovator Ornette Coleman (she would later marry Edwards in New York, in 1975). Cortez is a figure that links the avant-garde black music scene of the 1950s with early creativity in a black nationalist vein that came forth in the next decade. She helped found the Los Angeles chapter of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and cofounded Studio Watts, a space that offered students training in visual, performing, and language arts beginning in 1964. Between 1964 and 1966 she created projects that can be described as performance pieces, combining literature, jazz, visual art, and politics. It wasn't until 1969 that Cortez published her first book of poems, Pisstained Stairs and the Monkey Man's Wares, featuring drawings by Edwards.

Chicago-born White had come of age as an artist in the 1930s under the influence of social realism and progressive politics. With his incredibly detailed, expressive, and monumental paintings and drawings of black figures, White, along with Jacob Lawrence, was among the most visible and successful African American artists up to that moment. Ongoing health concerns caused him to move to the Los Angeles area in 1956, where he became involved with artists in Hollywood circles. He continued to pursue his interest in the figure as well as politically powerful imagery but began placing his figures in increasingly abstracted settings. Although his career was in full swing in New York and Europe from the 1940s onward, White was initially invisible to the mainstream arts infrastructure of the West Coast. His first solo exhibition in Los Angeles is emblematic of the cultural climate facing African American artists at the time, in which growing visibility within their own community did not translate into broader reception. White's weeklong show at the University of Southern California in April 1958, presenting thirteen drawings and prints, was introduced by Harry Belafonte, one of the hottest black stars of the moment, with whom White had begun collaborating upon his arrival in the city. The presentation was sponsored by the State Association of Colored Women's Clubs and the Southwest Symphony Association, a collective of black classical musicians, and yet failed to gain critical attention from the larger art establishment.

White began showing with Heritage Gallery in 1964. That same year he completed the large ink- and-charcoal drawing Birmingham Totem, an homage to martyrs of the civil rights struggle, in particular the four girls killed the previous year in the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. A younger generation of artists connected with White's activist voice when he began teaching at Otis Art Institute in 1965, where his students included David Hammons, Suzanne Jackson, Alonzo Davis, Dan Concholar, and Timothy Washington.

Pajaud, who had settled in Los Angeles in the late 1940s, was a key figure in two noteworthy events marking the coalescence of a black community of artists in the city. The first was the significant but short-lived co-op gallery known as Eleven Associated, which was active for about a year in the early 1950s. The eleven member artists—among them Beulah Woodard, Alice Gafford, Curtis Tann, and Pajaud—rented a space on South Hill Street as a way to gain visibility for their practice and to control more thoroughly their creative market. Pajaud's biblically themed watercolor Holy Family (c. 1965) is indicative of his artistic thinking during this period with its delicate ink drawing combined with washes of floating color.

The second event was Pajaud's appointment in 1957 as an art director at Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company, where he would also serve as director of public relations and eventually vice president. Arguably the largest African American–owned business in Los Angeles, Golden State expanded its power in a city whose growing black population was still denied access to most financial instruments. The company had a history of supporting African American artists: it commissioned New York painters Hale Woodruff and Charles Alston to create murals for its 1948 building designed by architect Paul R. Williams, and sculptor Richmond Barthé fashioned a bust of Golden State's founder, William H. Nickerson. With encouragement and direction from Pajaud, the company began building an art collection in earnest during the 1960s, featuring works by local African American artists such as Woodard, White, Saar, and John Riddle, and national artists such as Elizabeth Catlett and Jacob Lawrence. The company also purchased African art, including masks and sculpture from the Ivory Coast and Gabon. Golden State made its art holdings accessible as an educational tool through public tours as well as in printed catalogues.

ASSEMBLING

Assemblage is the style most often identified with artists in California in the late 1950s and early 1960s, coinciding with the rise of galleries such as Ferus, Huysman, and Dwan, and activity at the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum of Art). With artists such as Edward Kienholz, George Herms, and Wallace Berman, among others, the West Coast became highly visible and assemblage gained mainstream acceptance as an important artistic strategy, particularly with its canonization in the Museum of Modern Art's 1961 exhibition The Art of Assemblage. It is often seen as a form of critical practice, with notions such as the fraud of 1950s consumer society and its platitudes laced through the ruined consumer products of assemblage's facture. Embedded in the narrative of this method too is the concept of transformation, the alchemy of taking a thing discarded and changing it into a thing of (re)use.

Assemblage factors in the work of numerous artists included in Now Dig This!, although they approach it from a variety of directions: as stylistic exercise, as metaphoric narrative, and as spiritual exploration. Daniel LaRue Johnson and Ed Bereal, in particular, were identified early on in more general discussions of West Coast assemblage as well as of the emerging gallery scene in Los Angeles and activity around Chouinard Art Institute, which they both attended.

Johnson's work appeared in Directions in Collage: Artists in California (1962) at the Pasadena Art Museum, and in the California Annual of 1963 he was singled out as a significant talent to watch, along with Richard Pettibone and Dennis Hopper, for his black-box works. Incorporating fragmented doll parts and other black-lacquered objects on a black ground, these works, such as Untitled (1961), seem prescient of the violence against civil-rights and other activists that was becoming increasingly visible in the national and international media. Such pieces also take on the complexities of black as both color and social signifier explored by a number of other artists of the period, including Fred Eversley, as in his large disk Untitled (1976), and the Bay Area's Raymond Saunders, in particular his polemical pamphlet Black Is a Color (1967). Like Edwards, Johnson received important awards of recognition in the first half of the 1960s, including a John Hay Whitney fellowship (1963) and a Guggenheim award (1965), which enabled him to spend a year in Paris. Big Red (1964), a painting with collaged elements, marks the transition from Johnson's black pieces to the brightly polychromed monoliths that would be his focus later in the decade and in New York.

Both Johnson and Bereal were featured in the important 1964 Boxes show at Dwan Gallery, which contextualized the work of younger artists with historical constructions by the likes of Marcel Duchamp and Joseph Cornell. Bereal was identified as part of the "boys club" that emerged from Chouinard and came to represent the era, including Ed Ruscha, Joe Goode, Larry Bell, and Llyn Foulkes; like many of those artists, Bereal was also mentored by Robert Irwin.

Then came 1965 and the Watts rebellion—the largest urban uprising in U.S. history up to that moment. Dazed and angered by the violence and destruction, Bereal began to question his practice, his involvement with art as a high-end luxury good, and his place as a token figure in that world. He stopped making objects. By 1968 he was leading classes in African American studies at the University of California, Riverside, in tandem with teaching painting, drawing, and eventually video at the University of California, Irvine, a position he would hold for twenty-five years. By 1969 Bereal had moved into performance and video. His troupe, Bodacious Buggerrilla, specialized in radical and street theater that offered caustic critiques of institutional racism and oppression. Bereal also performed collaboratively with two other legendary Los Angeles groups during this period, spoken-word artists the Watts Prophets and legendary pianist Horace Tapscott and his Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra (with whom Jayne Cortez had performed as well).

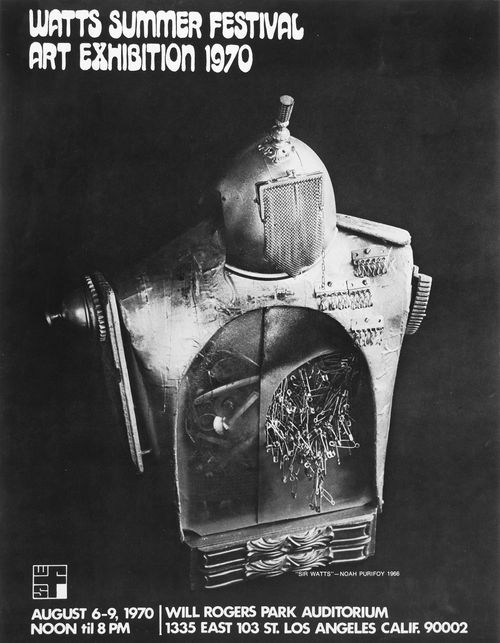

For other artists such as Noah Purifoy, who claimed that the Watts rebellion is what actually made him an artist, that event proved to be an inspiration. Purifoy, John Riddle, and John Outterbridge reinterpreted Watts as a discursive force, emblematic of both uncompromising energy and willful re-creation, using the artistic currency of assemblage. Purifoy and Riddle made formally impressive and highly charged mixed-media constructions from the detritus of the rebellion, which had shocked the world by erupting in the utopian paradise of California. With assemblage, these artists could refer to the complexities of African American culture and life without having to rely on simplistic painted representations of the black figure. A year after the insurrection, Purifoy, then director of the Watts Towers Arts Center, organized the seminal exhibition 66 Signs of Neon, which featured assemblages made of the vestiges of the urban rebellion, including his own Watts Uprising Remains (c. 1965–66).

Riddle, another Los Angeles native, began to connect with a community of African American artists around the time of the Watts uprising; he met some of these artists while sifting through the postrebellion rubble. Although he had been drawn to assemblage before that time, August 1965 put a new spin on things; he began to think hard about art's purpose. His Ghetto Merchant (1966), which probably was included in the 66 Signs of Neon exhibition, is anthropomorphic in sensibility, incorporating a burned-up cash register as its core element, its wiry keys forming a skeletal torso and providing an apt metaphor for a figure that preyed on the Watts community.

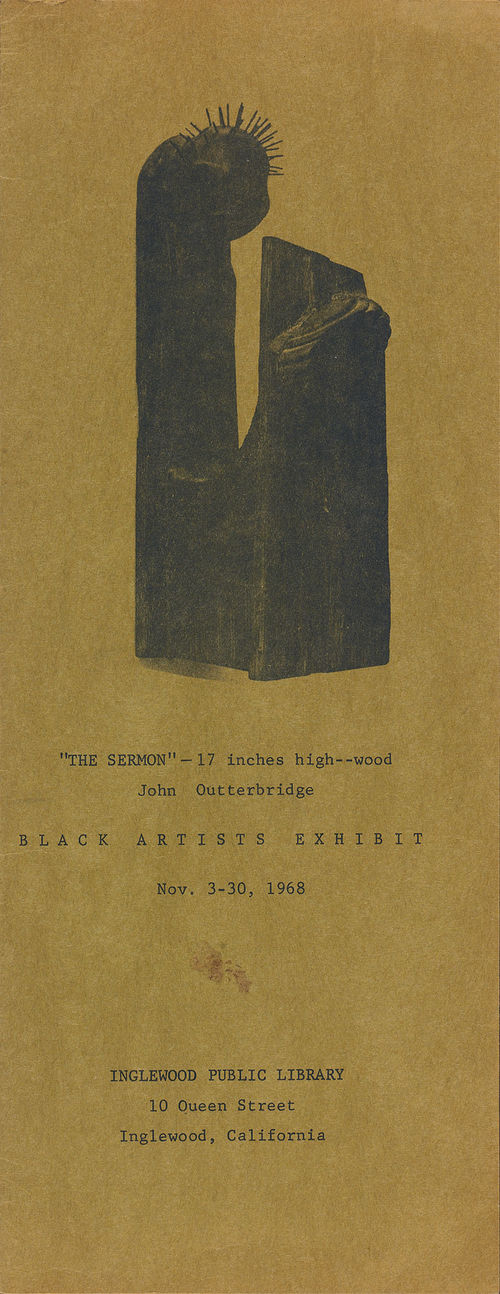

For Outterbridge, who arrived in Los Angeles from Chicago in 1963, politics, like any other element of assemblage, was just another material manifestation that could be incorporated into art. The mid-1960s was a time when the wall between the studio and the street was permeable. In this spirit, Outterbridge also held important community art positions at the Compton Communicative Arts Academy and the Watts Towers Arts Center.

Saar, too, mined assemblage's mode of institutional critique in pieces such as Let Me Entertain You (1972). Yet much of her work in this genre explored ritual and spiritual avenues, and increasingly those related to cosmologies of Asia and the African Diaspora, as in her altar works such as Indigo Mercy (1975) and Spirit Catcher (1977). Saar became a beacon for younger artists interested in a multimedia practice that more often took the form of installation and performance.

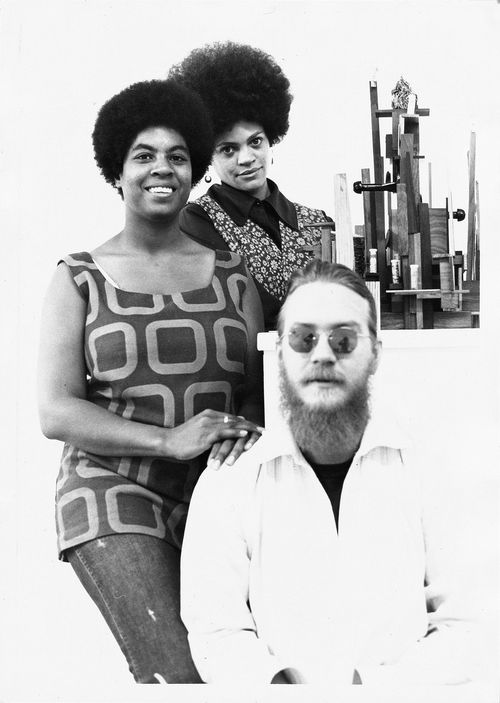

ARTISTS/GALLERISTS

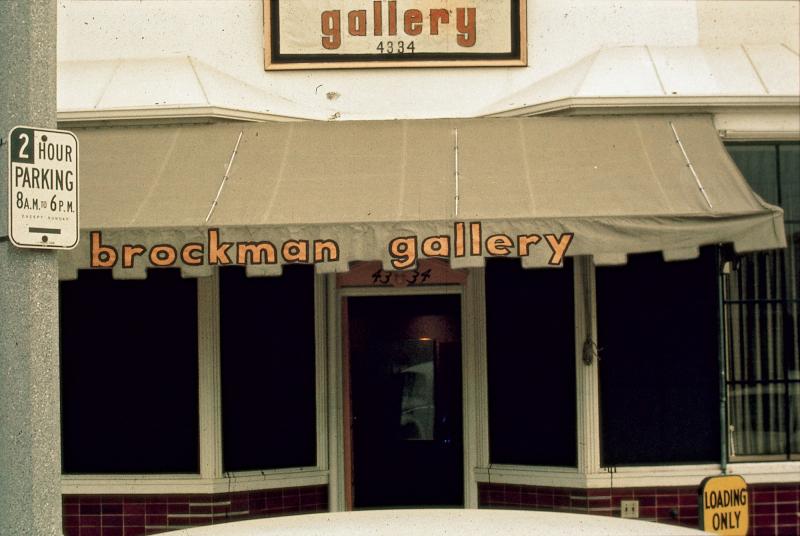

Lacking representation in mainstream institutions, African American artists opened their own venues in the 1960s and 1970s. Spaces such as Gallery 32, founded by painter Suzanne Jackson, and the Brockman Gallery, established by brothers Dale and Alonzo Davis, a sculptor and a painter, respectively, became sites for cutting-edge work and havens for discussions, poetry readings, and fund-raisers for social causes. Samella Lewis was an amazing one-woman institution, opening several galleries and a museum, starting a magazine, and publishing some of the earliest books on this cohort of artists. These spaces, and the artists who ran them, played an important role in the progressive struggles of the period while contributing to the diverse art scene in Los Angeles.

The Davises opened the Brockman Gallery in 1967, a year after a cross-country road trip allowed them to see and experience what artists were up to across the United States. Named for their maternal grandmother, who had been a slave, the gallery was dedicated primarily to the work of African American artists. In existence for more than twenty years, the Brockman Gallery produced hundreds of exhibitions, instigated a mural program, and hosted concerts; many of the artists featured in Now Dig This! showed there at some point in their careers.

Jackson had been a professional dancer before moving to Los Angeles in 1967. She was both an artist's model and a student in Charles White's classes at Otis, and she initially supported herself working concurrently as an elementary school art instructor and at the Watts Towers Arts Center teaching dance and visual art. Searching for a new studio space in the vicinity of both Otis and Chouinard, Jackson found a beautiful place on Lafayette Park and was encouraged by friends to turn it into a gallery. Open for two years, Gallery 32 had a somewhat more experimental and political edge, as in the 1969 works on paper show by Black Panther minister of culture Emory Douglas or the 1970 Sapphire Show, purportedly the first exhibition in Los Angeles focusing on black women artists.

Lewis arrived in the city in 1964, as a mid-career artist and academic, with a PhD from Ohio State University and fifteen years of teaching under her belt. She developed groundbreaking projects in Los Angeles that would distinguish her as a major champion of African American artists in the twentieth century. Her various galleries—The Gallery, Multi-Cul, and Gallery Tanner—would culminate in the Museum of African American Art, founded in 1976 (still in existence).

Lewis coedited with Ruth Waddy the first volume of Black Artists on Art in 1969, followed by a second volume in 1971. Many of the contributors, not surprisingly, were from California, and in effect the project reproduces those networks of African American artists stretching from the 1950s to the contemporary moment. These self-published and highly influential books highlighted the work of almost 150 contemporary African American artists, an amazing number given Lewis's resources and compared to the one or two figures typically showcased in mainstream contexts (even today). As a way to keep the ideas updated, Lewis, along with Val Spaulding and Jan Jemison, founded the magazine Black Art: An International Quarterly in 1976. This first periodical devoted to African American and African Diaspora artists would later change its name to International Review of African American Art. It is still in print. All during this period, Lewis continued to work full time in academia, as a professor at Scripps College in Claremont, California. In 1978 she translated her lectures on African American artists into the book Art: African American, which for decades was the standard academic text to introduce new students of all ages to these histories.

All of these upstart gallerists in the 1960s and 1970s were practicing artists, yet their own production generally is less recognized than the work of the artists they championed. Dale Davis produced clay pieces, such as Viet Nam War Games (1969), that place him in dialogue with important efforts in ceramics in California during this period. Jackson's lyrical acrylics such as Watch Mist (c. 1975) anticipate the neoexpressionist 1980s and the style of Italian painter Francesco Clemente. Lewis, a painter, has also experimented with printmaking throughout her career, as seen in the layering of paper and newsprint in Twentieth Century Wisemen (1968).

POST/MINIMALISM AND PERFORMANCE

A number of artists in Now Dig This! moved away from didactic subject matter connected more explicitly with narratives of civil rights and black power and toward more abstract, dematerialized, and conceptual modes of the period. Fred Eversley was the most visible African American working within the particular brand of minimalism that developed in Los Angeles in the 1960s. During the 1970s artists such as Senga Nengudi, Maren Hassinger, and David Hammons began to experiment with postminimal directions in ephemerality and performance.

Born in Brooklyn, Eversley started his professional life as an engineer. He moved to Southern California to take a position in the aerospace industry, living at Venice Beach, where the bohemian culture inspired him to become an artist. Using plastic resin, he developed a formal sculptural language that reflected the West Coast style that came to be known as "finish fetish," a seemingly more decorative approach to minimalism that appeared to take its cues from the synthetic materials and mechanized surfaces of hot rods, surfboards, and the aerospace industry. Advancing toward immaterial luminosity and perception, Eversley's sculptures from the period are concerned with transparency, kineticism, optical properties, and mathematical tautology.

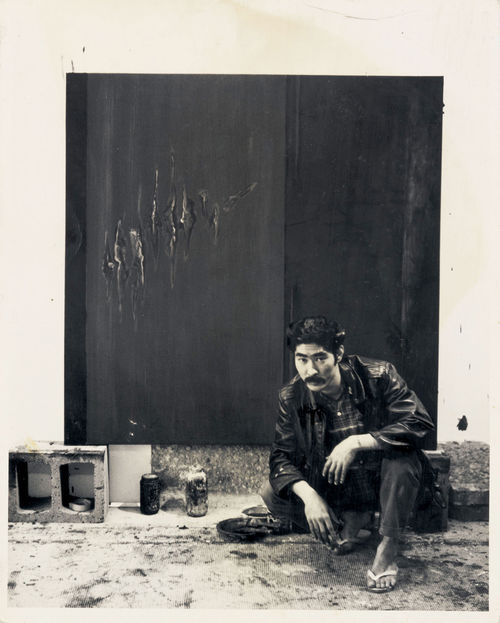

Hammons arrived in Los Angeles from Springfield, Illinois, in 1963. He studied art at various institutions throughout the city, eventually seeking out Charles White at Otis Art Institute. White's influence on Hammons can be seen in the younger artist's early choice of the graphic medium as well as in the political content of his work. Yet as Hammons developed his famed body prints, he demonstrated their basis in multimedia tradition more broadly construed, as evidenced in works such as Blue Female (1970s). Hammons's shift toward three dimensions and spatial aesthetics can be seen in the assemblage Bird (1973), as well as in his work in performance. Such experiments were done in conjunction with Studio Z. This loose group came together at Hammons's studio on Slauson Avenue—sometimes weekly—to engage in spontaneous actions, some of which were performed on the streets of the city. Studio Z had a changing membership (if one can call it that), including at various times Franklin Parker, Houston Conwill, Ulysses Jenkins, and RoHo along with Hammons, Hassinger, and Nengudi. Hammons's studio, a huge old dance hall with a wooden floor, was a perfect place in which to work out ideas.

Both Nengudi and Hassinger came to performance from the study of dance. In graduate school at UCLA in the early 1970s, Hassinger discovered what would become a pivotal medium for her: wire rope. In her hands this material came to embody the changing landscape of American sculpture from minimal to postminimal: it was a synthetic substance that, with subtle intervention, could echo organic form. These solid and industrial yet process-driven sculptures initiated activity, lending themselves to the temporality of performance. One of Hassinger's first performances, High Noon, took place within an installation of her sculpture at the ARCO Center for Visual Art in 1976. With her 1981 exhibition Dangerous Ground, Hassinger became the first African American to have a solo show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

While a graduate student at California State University, Los Angeles, in the late 1960s, Nengudi worked both at the Pasadena Art Museum and at the Watts Towers Arts Center, drawing inspiration from mainstream sources as well as those that privileged black creativity. Nengudi's experimentation with dematerialized form during this era resulted in series such as the Water Compositions—her singularly less hard-edge take on Los Angeles minimalism—and Répondez s'il vous plaît, or RSVP, pliable pieces composed of pantyhose and sand. In the case of both Hassinger and Nengudi, the ephemeral nature of the work, combined with anemic commercial interest at the time, means that few pieces from the period survive. Now Dig This! presents new installations by Nengudi and Hassinger that capture the confrontation with the city that both artists experienced in the 1970s; performance also plays a role in this new work.

In 1982, as part of the opening festivities at the Municipal Art Gallery in Barnsdall Art Park of the important traveling exhibition Afro American Abstraction, in which they both appeared, Hassinger and Nengudi created a new performance piece called Flying. Its title suggested a hope for the future for their work and that of their fellow travelers—a launch into new arenas of acceptance and success. Collaborating with Hassinger and Nengudi were Franklin Parker—who had appeared in Nengudi's Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978), which took place under a section of freeway—and Ulysses Jenkins, whose work combined video and performance; the use of mobile TV monitors in Flying bespeaks his influence. When Hammons finally relocated permanently to New York and gave up his large studio, Jenkins's place became the new hub of performance activity. Numerous artists appeared in Jenkins's video pieces from the period, and Nengudi and Parker would work with him in 1987 on Cats in the Catnip—Rollin' Around in the Hay, a performance in Barnsdall Art Park.

Originally from Los Angeles, Jenkins had studied at Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, before returning to Southern California and committing himself to mural projects in the 1970s (working with both Alonzo Davis and Brockman Productions as well as with Judy Baca on The Great Wall of Los Angeles). He became part of the Video Venice Collective during this time. After receiving his MFA from Otis Art Institute, Jenkins began teaching. He was on the faculty at the University of California, San Diego, from 1979 to 1981, in a department that also included Eleanor Antin, Allan Kaprow, Tony Conrad, and Louis Hock, among others. In 1993 he went to the University of California, Irvine, filling the spot teaching performance and video recently vacated by Ed Bereal.

Like his predecessors a decade earlier, Jenkins began finding and creating alternative avenues of support when art-world doors appeared closed to him. He opened his own studio as a performance space, launching Othervisions Studio. His Othervisions Band performed in local dance clubs such as Club Lhasa in the early 1980s. Jenkins's video work ranges from vérité, in pieces such as Remnants of the Watts Festival (1972–73, compiled 1980) and In the Spirit of Charles White (1970), to more experimental works made with a style of choppy editing he calls "doggereal."

Now Dig This! documents the development of a major community of African American artists in Southern California. Yet such communities are often defined by their very permeability and reach. Even as African Americans were founding their own institutions and hewing their own path in the national and international art worlds, they had a network of friends who helped and championed them, and who were not always African American. An important component of this exhibition is the exploration of the relationships between black artists in Los Angeles and other communities of practitioners, whether nonblack artists with whom friendships and coalitions were formed or African American artists in other parts of the country. Such connections elucidate the relationships that move artists and art worlds forward.

Eleven Associated, the co-op gallery of African American artists active in Los Angeles in the early 1950s, had one Asian American member, Tyrus Wong. A painter of delicate watercolors, Wong was also a Disney illustrator whose drawings were integral to the 1942 film Bambi. Pajaud, another member of Eleven Associated, is said to have studied with Wong, and one can clearly discern the similarities of brushwork, inspired by Chinese painting, in Pajaud's pictures. Sculptor Mark di Suvero would figure in the lives of two others in this show on separate occasions. The construction of the massive armature for the Artists' Tower of Protest, also known as the Peace Tower, a public antiwar sculpture in Los Angeles in 1966, was carried out by di Suvero and Edwards, who met through the Dwan Gallery. A bit later, while constructing a piece on the site of the Pasadena Art Museum, di Suvero met Outterbridge, who happened to work there. Upon seeing Outterbridge crafting metal sculpture by hand, di Suvero gave him an extended loan of his power tools. From this act, Outterbridge's Containment Series was born.

Other artists met in academic settings. Ron Miyashiro became friendly with Daniel LaRue Johnson and Ed Bereal at Chouinard Art Institute. Both Bereal and Miyashiro appear in the infamous poster for the War Babies show at Henry Hopkins's Huysman Gallery in 1961. Each of four figures holds an item stereotypically emblematic of his ethnicity or religion: Bereal, a slice of watermelon; Miyashiro, a bowl and chopsticks; Jewish artist Larry Bell, a bagel; and Catholic artist Joe Goode, a can of herring. Miyashiro also had a studio next door to Edwards on Van Ness Avenue in Los Angeles and later on Canal Street when both moved to New York. Johnson and Virginia Jaramillo, who married in 1960, met through a mutual art teacher when they were both budding artists at Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, which also produced the likes of Jackson Pollock and Philip Guston. Jaramillo's Structure Nine (March 5, 1965) is a textured canvas that approaches West Coast minimalism from painting as opposed to sculpture.

Political activism was another factor drawing people together across racial lines. Not all artists who worked with Purifoy on the 66 Signs of Neon exhibition were African American, yet they were committed to the project and to Purifoy's leadership of it. Gordon Wagner, a white artist who worked in assemblage, contributed important works to this show.

Chicano artists created their own activist art groups during this era as well. Much of the early aesthetics in these organizations centered on the creation of political posters—affordable placards that could be used in demonstrations and easily displayed in people's homes as works of art. Outterbridge, after accepting a job to run the Compton Communicative Arts Academy, came into contact with others who were involved in building alternative creative institutional structures, such as Mechicano Art Center, begun in 1969. One of the artists involved with Mechicano was Andrew Zermeño, whose poster work from the period such as Si La Raza no para a Nixon, Nixon aplastará a La Raza (Unless La Raza Stops Nixon, Nixon Will Stomp La Raza) (1968) is emblematic of the politicized aesthetic of the time.

The women's movement on the West Coast is well known for its institution building in Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro's Feminist Art Program begun in Fresno in 1970, and the opening of the Woman's Building in Los Angeles in 1973. Graphic designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville was integral to the emergence of the latter. Her friendship with Saar at the time resulted in a lifetime of collaborations. In 1973 Saar organized the earliest exhibition devoted to women of color at Womanspace, the predecessor to the Woman's Building. Titled Black Mirror, the exhibition included her own art along with that by Lewis, Jackson, Gloria Bohanon, and Marie Johnson (Calloway). Saar's work adorned the cover of Chrysalis, no. 4 (1977), a Woman's Building publication designed by de Bretteville, who would also go on to shape a number of Saar's exhibition catalogues, including Secrets, Dialogues, and Revelations: The Art of Betye and Alison Saar in 1990 at Wight Art Gallery of UCLA. Eversley, who lived in Venice Beach, was one of the few African Americans involved in that largely white scene. When his friend the painter John Altoon passed away in 1969, Altoon's widow, Babs Altoon, gave the studio to Eversley. He lives and works there to this day.

African American artist Houston Conwill created ritual space as installation and performed as part of Studio Z as well as in collaboration with his wife, Kinshasha Holman Conwill. His sculpture Drum (c. 1975–80) possibly dates from his work with Nengudi on their 1980 performance Getup. Another performance by Conwill, Warrior Chants, Love Songs, and New Spirituals (with poets Kamau Daáood and Ojenke, and sculptor Charles Dickson), took place at the Watts Towers Arts Center in 1979.

It is important to note that Brockman Gallery, Gallery 32, and the multifarious projects initiated by Samella Lewis were run by African Americans. While they were created to provide exhibition opportunities and visibility for an African American art community that was underserved by the mainstream art world, their profile always included nonblack artists. Elizabeth Leigh-Taylor's engaging portraits of black women, Sharona (1967) and Angela (1970), the latter of activist Angela Davis, and her inclusion in exhibitions at Gallery 32 often lead people to mistakenly assume the artist is African American rather than Anglo American. Printmaker and Franciscan nun Karen Boccalero was a founder of Self Help Graphics, another Chicano group dedicated to radical poster and print projects, such as her own silk screen In Our Remembrance/In Our Resurrection (1983). Alonzo Davis was also interested in printing techniques and produced several works with that organization.

In terms of geographic diversity, African American artists in Los Angeles had a special bond with fellow black artists in Northern California. Painter Raymond Saunders was friendly with both Saar and Eversley. Joe Overstreet, an experimental painter with ties to the Bay Area Beat scene, was related by marriage to Hammons. Calloway and Saar had tandem solo shows at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1977. Calloway organized a number of exhibitions featuring black artists from throughout the state, including Twentieth Century Black Artists at the San Jose Museum of Art, which was sponsored in part by the Santa Clara County Black Caucus. The multimedia practice of Saunders, Overstreet, and Calloway bespeaks aesthetic links to their Southern California friends as well. After experiments with large-scale acrylic painting, Charles Gaines began to create photo-based conceptual works such as FACES: Set #4, Stephan W. Walls (1978). Like the performative practices of Hammons, Nengudi, and Hassinger, his method signaled the changing directions of a new generation. Gaines lived in Fresno until 1989, when he took a position at California Institute of the Arts.

In 1974 Linda Goode Bryant opened Just Above Midtown Gallery (JAM) on West Fifty-Seventh Street, New York's elite gallery row. A former employee of both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Studio Museum in Harlem, Goode Bryant created the venue to provide an alternative for African American artists (and others) whose work was pushing boundaries. The inaugural exhibition Synthesis included Los Angeles–based practitioners Hammons, Concholar, Jackson, Alonzo Davis, and RoHo. JAM did more than any other gallery to introduce the work of the black West Coast to New York on a large scale and in a consistent manner. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s a number of the artists in Now Dig This! headed to New York intent on making it in that art mecca. Edwards, Cortez, Johnson, and Jaramillo were among the first wave in the 1960s. By the end of the 1970s Overstreet, Hammons, Hassinger, Houston and Kinshasha Conwill, and Concholar had joined them. Most certainly the presence of these artists on the East Coast affected New York's expanding discourse in the 1980s and beyond in terms of both visual and cultural diversity.

During a sweltering week in July 2009 a team of researchers descended on a warehouse in New Jersey and took a first pass at organizing JAM's extensive archive, which Goode Bryant had preserved for thirty-five years. The changing group of experts affectionately known as "Kellie's Angels" (including that week Kalia Brooks, Dasha Chapman, and Naima Keith) were led to a piece of bright orange hard-sided luggage. It had been brought to New York from Los Angeles, Goode Bryant assured us, by Concholar. He worked at JAM when he arrived from the West before taking up other positions in arts administration in New York City. Several prints were unearthed inside, including Ruth Waddy's Pomegranates (1966) and George Clack's Destruction of Peace (1960s). Both artists had been active in the Los Angeles scene of the 1960s and 1970s. Waddy became an artist late in life, and in the early 1960s art was her preferred method of organizing social and political work and civic action; for Waddy, art had another "social value": it made people think. She founded the artist's group Art West Associated in 1962 to press mainstream arts institutions in Southern California for greater African American representation. She was also co-editor with Lewis of the groundbreaking Black Artists on Art books.

Bills and a gentleman's magazine jostled for space in the suitcase too, along with various art supplies. As we dug further we realized that it was not soot that colored our archival gloves but a trail from a bag full of powdered graphite. This was one of Charles White's preferred media in the later part of his career. It explained the monogram CW on the suitcase closures: Concholar, after all, had been a student of White's. Our story had come full circle.