Defending Black Imagination

Artists always think we're in danger.

—Varnette Honeywood in Varnette's World: A Study of a Young Artist (dir. Carroll Parrott Blue, 1980)

It is not called "show art," we are frequently reminded, but "show business." Artists everywhere have struggled with the complex relations that obtain between creative expression, material necessity, and the market. But for artists working in the entertainment capital of the world, the stakes would seem to be especially high either to reject the aesthetic and business models exemplified by Hollywood or to assimilate them. For Los Angeles–based artists who are black, furthermore, the complex legacy of black performance (so aggressively confined to modes aimed at pleasing white audiences) complicates efforts to be taken seriously as creative agents and to develop affirming creative practices that are financially sustainable, let alone autonomous. This essay describes some of the ways in which a group of emerging black artists in Los Angeles in the 1970s navigated the show/art/business divides while working in Hollywood's own medium of film. These filmmakers generated a body of work that reflects and reflects upon the ongoing difficulties of maintaining black creative voices in L.A.'s particular political and industrial climates. In developing their own cinematic voices in an academic environment outside of the dominant film industry, they posited that black creativity is not frivolous or secondary to political change but fundamental to any attempt to restore and preserve the well-being of black individuals and communities.

Dubbed the "L.A. Rebellion" by Clyde Taylor and the "Los Angeles School of Black Filmmakers" by Ntongela Masilela,# this diverse group of artists studied filmmaking at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), between the late 1960s and the early 1980s. This setting locates them at the nexus of intense local political activity and university initiatives to recruit students from underrepresented racial groups, as well as vigorous theoretical debates about film aesthetics and reconsiderations of the role of art in efforts to effect social change. This generation had come of age during the civil rights movement and expected to see significant social and political gains for black communities. Thus the persistence of race-based inequalities into the 1970s grew increasingly frustrating and shaped their work in profound ways.

Most accounts of this group focus on how these artists tried to develop film styles that challenged the condescending and disingenuous treatment of black people in film, not just on the screen but behind the camera.# For example, many of them found the "Blaxploitation" fare that was being distributed to black neighborhood theaters to be as problematic as the classic Hollywood movies they had watched growing up. Both types of films were made and circulated primarily by whites, leaving black people with extremely limited control over the making and exhibition of their own media images. Thus, the attempts by many of these filmmakers to resist the co-opting of black creativity by the dominant film industry and to develop a distinct black film aesthetic constituted a complex balancing act. How could they address the socioeconomic plight of black people still struggling for rights and recognition (including L.A.'s disenfranchised black populations) and at the same time develop their own personal artistic visions and chart individual career trajectories, all in the long shadow cast by Hollywood?

Across their diverse early works, we see these filmmakers allegorizing this dilemma, taking up the question of how to keep the imaginations of black people alive in an environment that threatens both to crush black creativity and to exploit it. Though quite varied in form and style, these films share a self-reflexive impulse to examine the challenges L.A. poses as a particular site in the twin struggles for creative freedom and black liberation. We see this in Charles Burnett's narrative feature Killer of Sheep (1977) and in Barbara McCullough's experimental short Water Ritual #1: An Urban Rite of Purification (1979). Aspects of Burnett's and McCullough's individual struggles to get their films made are echoed in their characterizations of black people seeking to express themselves creatively in relentlessly oppressive conditions.

Killer of Sheep is perhaps the best-known student film of the "L.A. Rebellion" group. Made over roughly a year of weekends toward the end of Burnett's student days at UCLA (he nursed his student status for some ten years to maintain access to the film department's equipment and facilities), Killer of Sheep features numerous haunting sequences showing black children at play, some of whom Burnett enlisted to help shoot the film. We see them playing in bleak and dangerous South Los Angeles landscapes—as strong men attempting to crush each other under the wheels of railroad cars, as superheroes leaping across apartment-complex rooftops, as warriors pelting each other with rocks and gravel in vast empty lots. The lack of safe recreational facilities for black youth is one of many indicators of the massive divestments that stripped these communities of social services, employment opportunities, and educational resources, particularly after the Watts uprising of 1965. Although we might read the children's imaginative play in Killer of Sheep as symbolizing the triumph of the human spirit, or black endurance in particular, it also has a palpably tragic dimension. Rendered in extended, on-location shots filmed in 16mm black and white, the film's cinema vérité style evokes grave concern about the physical and psychological well-being of these children and their community as a whole.

McCullough's Water Ritual #1 examines the ongoing, hard-fought struggle for spiritual and psychological space through improvisational ritual acts performed by a black woman. Also shot in 16mm black and white, the film was made in an area in Watts that had been cleared to make way for the I-105 freeway.# The film begins, as Ntongela Masilela describes it, with a woman named Milanda "sitting in the crumbling frame of a building in a desolate urban landscape."# At first sight, this black woman (wearing a simple dress and scarves on her head and around her waist) and her environs might seem to be located in Africa or the Caribbean, or at some time in the historical past. It is not until we get a very brief shot at a longer distance, in which a set of houses and a passing car are visible behind the barren lot with woman and "crumbling frame," that we get the impression that this is a scene of contemporary American urban life. This layering of locations and temporalities—of the Third and First Worlds, of the present and the past—continues through to the film's controversial conclusion, in which a now nude Milanda squats and urinates on the broken, burned-out ground inside of another urban ruin. By making "water," Milanda is connected to the numerous female water-based figures in African Diaspora cosmology. In this act, Milanda attempts to expel the putrefaction she has absorbed from her physical environment, while symbolically cleansing the environment itself.

Burnett and McCullough underscore the interconnectedness of the threats to black bodies and minds in South Los Angeles in their renderings of the community's physical environment. The sprawling, sun-bright terrain has contributed to the mythology of L.A. as a place that offers greater freedom and possibility to black people than do cities of the East and the Midwest, attracting so many Southern black migrants, including Burnett's own family from Mississippi, and McCullough's from New Orleans. But, as historian Quintard Taylor has observed, "[i]f impoverished black communities in Denver, Seattle, or Los Angeles seemed less visually alienating than Harlem, South Side Chicago, or Southeast Washington, the underlying conditions were remarkably similar." Indeed, the "Watts [uprising] reminded the nation that while the ghettos of the West seldom resembled Harlem's brownstone tenements or Chicago's high-rise public housing, they shared a foundation of poverty, alienation, and anger."# These are the conditions that have caused the lead character in Killer of Sheep, Stan, to become emotionally distant from the people around him, and have relegated Water Ritual #1's Milanda to her isolated state in a decimated terrain. Stan, a migrant from the South, has not found a sense of security or satisfaction in his employment at a slaughterhouse or in the South L.A. home he shares with his family. Instead, his gruesome job and his inability to insulate his family from the dangers and disappointments that characterize life in their community have permeated his psyche, rendering him unable to sleep and to share intimacy with his wife. Milanda's isolation was inspired in part by the mental breakdown of a female friend of McCullough's who retreated into "her own internal being."# Burnett and McCullough present the natural and architectural features of South Los Angeles as both causes and emblems of Stan's and Milanda's troubled mental states.

The South Los Angeles landscapes in these films signify obstacles and entrapment for those who lack the resources to sustain the lifestyles for which their communities were initially planned. There is a chain of abandonments in Water Ritual #1, in which the city has turned its back on black community residents, residents have vacated their homes, and the deserted homes leave remaining folks like Milanda stranded in a state of desolation. In Killer of Sheep, the region's rolling hills become the site of the film's most exasperating scene: a car motor that Stan and a friend have laboriously lugged onto the back of a pickup truck falls to the asphalt and cracks just as the truck jerks into gear on a sloping street. Tall, lush foliage engulfs Stan's home, echoing the claustrophobic framings of the people inside, most notably Stan's wife and daughter. L.A.'s ubiquitous single-family dwellings do not function in Killer of Sheep or Water Ritual #1 as symbols of community order or middle-class attainment, securing the sanctity or privacy of the nuclear family. Instead, like the rain that threatens to enter through Stan's leaky roof, visitors (some more welcome than others) regularly seep into his home. And behind Stan's house lies a network of alleys in which crime and confrontation are rampant. It is quite striking, then, when Stan pauses at his kitchen table for a brief flight of imagination, likening the warmth of a teacup against his cheek with the heat of a lover's embrace. But the reverie is fleeting, quickly dissolved by his friend Bracy's dismissive chuckles.

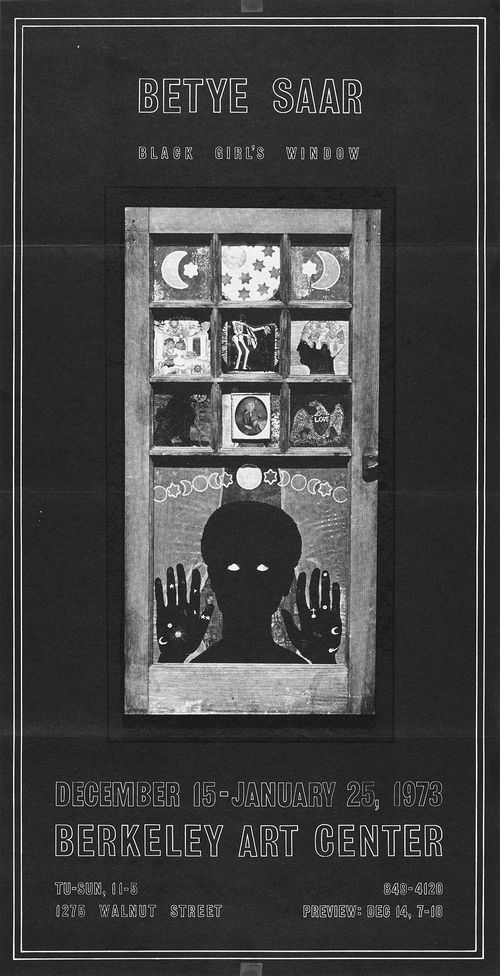

Would an audience full of Bracys view a tender film like Killer of Sheep with similar insensitivity, given that its tone is so markedly different from that of other films made about and for black urban audiences? And what about Water Ritual #1, a film that even some of McCullough's classmates giggled at or dismissed in discomfort?# Burnett and McCullough did not make these films with commercial release in mind, recognizing that such works could not reach black audiences in large numbers. Even when Killer of Sheep was released for the first time theatrically to mark its thirtieth anniversary, it attracted primarily art film audiences.# McCullough has said: "My viewers have to have an affinity for offbeat, unusual images and characters. Mine are projects that have a different type of orientation. My work is shown basically through the art community, video exhibits, things that are confined to a museum or gallery setting, or an art theatre type of presentation, rather than to a broad-based community-exposure type situation."# Though this art world has also been a racially exclusionary one, McCullough's connections with vanguard black visual artists in Los Angeles, including David Hammons, Betye Saar, and Senga Nengudi, gave her models for resisting the pressures to work in the mode of sociological realism, or to speak only to "the community" in a familiar way. Instead, attracted by the ways in which these artists were engaging ritual in their creative practices, as well as by the folklorist work of Zora Neale Hurston, McCullough attempted to create a unique cinematic experience for those she calls her "participant-viewers."

It is important to note that while McCullough, Burnett, and their fellow black students were strongly influenced by a range of black cultural forms (visual art, music, folklore) and political concerns facing the black community, they were also encouraged by their UCLA film professors to make films as art. They trained in an academic film program that stressed original and individual self-expression in deliberate contrast with the industry orientation of the rival University of Southern California. Although the members of the "Los Angeles School of Black Filmmakers" made films about black people, they were not necessarily made for mass black audiences, as they drew upon myriad cinematic styles in ways that could not result in films that would be marketed to black neighborhood theaters.

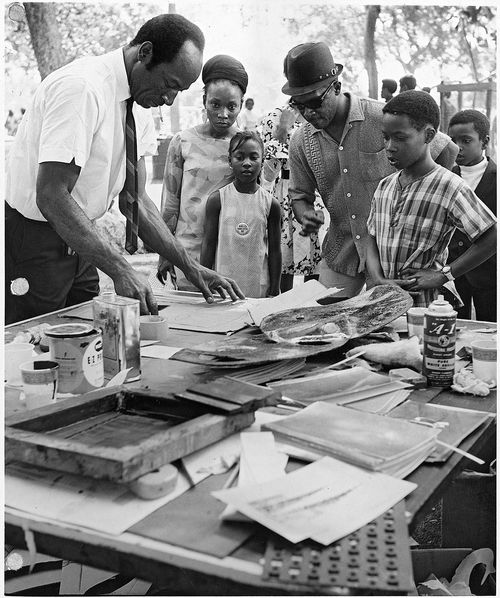

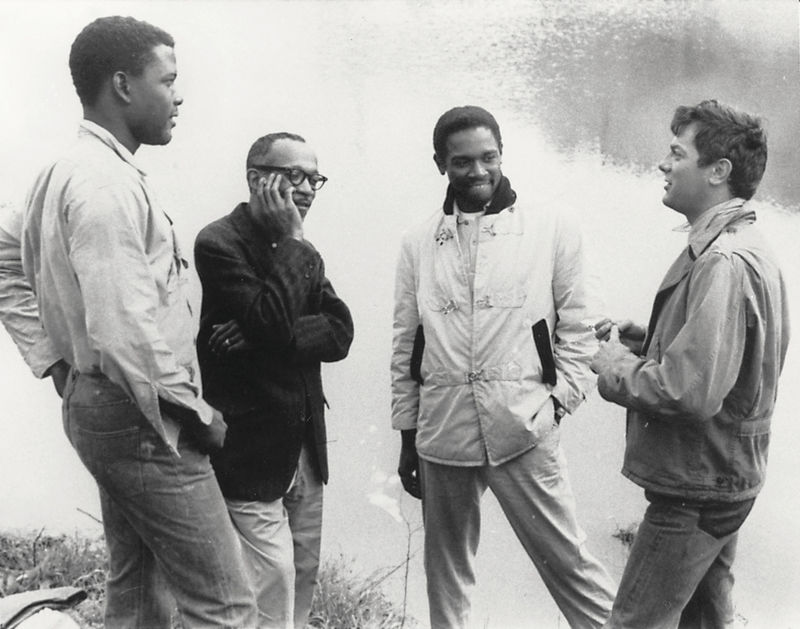

These filmmakers were exposed to many different types of films—narrative, documentary, and experimental, Western and non-Western—both in their classes and in the rich repertory and cinematheque scene in Los Angeles. Burnett has cited his instructor, English documentarian Basil Wright (who worked with John Grierson), as a major influence. Burnett and fellow graduate student Haile Gerima, an Ethiopian-born student who came to UCLA's graduate film program by way of the acting program, worked as teaching assistants to Elyseo Taylor, the film school's only black faculty member.# Taylor, who had served as a cinematographer in the U.S. Army, led the school's Ethno-Communications program, an initiative stemming from student protests that was designed to recruit and train undergraduate students of color in filmmaking, encouraging them to document their own communities. When Taylor left UCLA after not being granted tenure, Ethiopian graduate student Teshome Gabriel joined the faculty, teaching Third Cinema and mentoring many of the students of color who came through the program. UCLA film students saw not only canonical Hollywood fare and European classics but also postcolonial films from Africa and Latin America, along with various postwar European cinemas, from Italian Neorealism to French New Wave to the New German Cinema. Taking their cue from the revolutionary cinemas of Argentina, Brazil, and Cuba, many members of the "Los Angeles School" tried to create films that would raise political consciousness and inspire change. These and other models opened up ways to experiment with narrative structures, characterizations, and visual styles. Several "L.A. Rebellion" student films have been shown to black audiences in nontheatrical settings (community centers, churches, and the like) and found appreciative audiences among critics and scholars and in an international circuit of film festivals and retrospectives. But their formal experimentations have made it challenging to reach, en masse, the black communities about which they were made.

Melvin Van Peebles's film Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (1971) seemed to have successfully bridged this gap. Shot in Los Angeles, Sweetback was an independently produced feature that combined the disjunctive editing and impressionistic characterizations of an art film with social commentary, sex, and violence to become a box-office smash. The emerging white auteurs of American cinema who came out of film school in the years just prior, such as Martin Scorsese (MFA at NYU, 1966) and Francis Ford Coppola (MFA at UCLA, 1967), were profitably merging the edgy sensibilities of modernist European cinema and American exploitation films with conventions drawn from classic Hollywood genres (e.g., the gangster film and film noir). But, with the major exception of Jamaa Fanaka (who secured theatrical distribution for three features he made while still a student at UCLA), many in this first generation of university-trained black filmmakers did not reach, or perhaps even seek, commercial success.

The emphasis on creative self-expression and the general climate of student protest at UCLA at the time made the political and aesthetic critiques of Hollywood found in these films rather expected. But in making films that might not ever reach the communities they represent, the "L.A. Rebellion" student filmmakers took on what is perhaps an even bigger challenge: finding a place for the capital-intensive, Euro/American-identified medium of film within the constellation of politically engaged Black Arts being practiced in Los Angeles and beyond. What might be most rebellious about their work is that their university training allowed them to bracket commercial considerations temporarily (including those with aspirations to work within Hollywood eventually). At the risk of not reaching large black audiences, these student filmmakers cleared out spaces for exploring their own creativity, with an understanding that their individual artistic processes were linked to the larger project of black liberation.

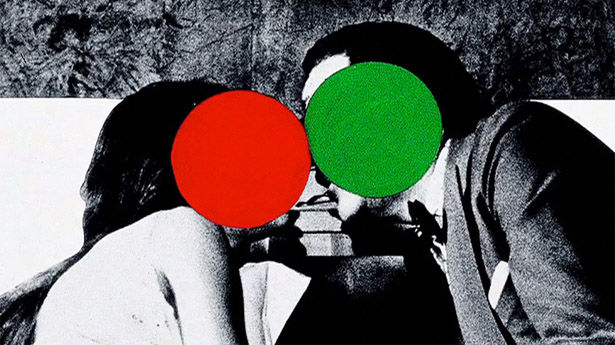

We see the thematization of the relationship between creative practice and political consciousness in numerous "L.A. Rebellion" films, such as Daydream Therapy (1980) by Bernard Nicolas. Born in Haiti and raised in Southern California, Nicolas had become a widely known student activist during his undergraduate years at UCLA and then turned to filmmaking in graduate school as a tool for political work. Daydream Therapy is set to Nina Simone's 1964 rendition of "Pirate Jenny"; Simone's reworking of the song adapts a scrubwoman's vengeance fantasy from Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill's The Threepenny Opera (1928) to the contemporary rise of black militancy. As Simone sings, Nicolas cuts between the black-and-white world of a black woman who cleans the offices of Los Angeles banks and her dreams, in color, of joining a group of black revolutionaries who murder a sexually exploitative white male boss. In the film we see the interplay of multiple aesthetic and political influences. The black woman's job, dress, and stoic demeanor echo those of the lead character in La Noire de . . . (Black Girl, 1966) by celebrated Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène. But whereas Sembène's film ends with the homesick African maid's suicide in her employers' bathtub in Antibes, Daydream Therapy concludes with a dynamic sequence of shots, edited at an increasingly rapid pace, in which the black woman's fantasy world provides her with inspiration to change her circumstances in the "real" world.

As the film cuts between shots of the woman walking briskly in both the black-and-white and the color footage, we see a quickly changing succession of objects in her hands in the color shots—Kwame Nkrumah's book Class Struggle in Africa; a sign that reads "Don't just dream, fight for what you want"; a camera; and finally a rifle. The rhythm and effect of the editing in this sequence call to mind Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid's pivotal L.A.-shot avant-garde work Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), in which match-on-action editing links shots of Deren walking with similar deliberateness across a series of different textures (sand, grass, pavement, rug) en route to stab her male lover. Though Daydream Therapy resembles Meshes in its use of symbolic objects and the interweaving of the conscious and unconscious minds, it also reworks Deren's concluding suicide: we know by the smile on the black woman's face at the end of the film that as she enters yet another high-rise bank building, signifying L.A.'s concentration of capital, she has connected her social and economic plight with that of others across the African Diaspora. If she is headed toward her death, it will be a courageous act of martyrdom; a closing title tells us that the narrative ends at "the beginning. . . ."

Nicolas's placement of a camera in the hands of his revolutionary black woman, along with Nkrumah's anti-imperialist book, a protest placard, and a rifle, illustrates the powerful role filmmaking is thought to play both for those who see revolutionary films and for those who take up the camera for the cause. Films can have revolutionary effects on audiences not just by documenting and analyzing political conditions or by modeling processes of politicization and methods of resistance, but also by serving as a therapeutic aspiration for those seeking release from oppressive conditions. Importantly, many "L.A. Rebellion" filmmakers represent filmmaking itself as a revolutionary and transformative creative activity. For example, in Julie Dash's thesis film Illusions (1983), a black woman passes for white in order to work as a studio executive in 1940s Hollywood, covertly advancing a racially progressive agenda, including the respectful treatment of a black singer. In Melvonna Ballenger's Rain (1978), a black woman typist is inspired by a flyer she received from a black male activist at a bus stop to leave her soul-killing office job and join the movement, assisting with the formation of a black filmmaking collective. These self-reflexive representations link the filmmakers to black people everywhere who suffer daily indignities, and they associate filmmaking with the development of a black revolutionary consciousness. As black film students, these filmmakers faced a range of oppressive forces. In their competitive university setting, they received harsh criticism from their teachers and classmates (sometimes amplified by racial and gender differences) and often met resistance from social forces beyond the campus. Gerima's Bush Mama (1976) famously features a scene of the film crew being harassed by members of the LAPD. These filmmakers were seeking to demonstrate how their own work reflects the state of the black community and contributes to the black liberation struggle.

Importantly, the filmmakers emphasize the threats to black creative efforts, whether in daily life in Los Angeles or in artistic practices. In Carroll Parrott Blue's short Varnette's World: A Study of a Young Artist (1980), for example, Varnette Honeywood describes how she makes time for painting while holding down a day job coordinating arts curricula for Los Angeles schoolchildren and participating in a local black artists collective seeking to secure scarce resources to continue their work. In Larry Clark's fictional drama Passing Through (1977), featuring revered L.A. jazz musician and activist Horace Tapscott, a young saxophonist named Warmack (played by Nathaniel Taylor) seeks to organize black musicians to start their own record label, challenging the control of the recording industry by exploitative and violent white gangsters. Blue and Clark explore the structural challenges these black Los Angeles artists faced in striving to sustain their own expressive practices while using art to forge and strengthen black community resistance. In doing so, their films implicitly ask how their own creative practices in the medium of film can survive and work on behalf of L.A.'s black community members.

The significance of the films of Burnett, McCullough, Gerima, Nicolas, Ballenger, Dash, Blue, Clark, and other members of the "L.A. Rebellion" cannot be measured by the number of black viewers they affected directly (though one would hope that greater numbers of viewers will see this work as scholars and programmers redress past, racially motivated oversights). Rather, it is the very discontinuity between the worlds these films present on-screen and the worlds in which they primarily have been viewed that allows us to appreciate how they function as works of community-minded black individual expression. Daniel Widener has documented how dozens of L.A.-based writers, musicians, and visual (plastic) artists organized between 1960 and 1975 in ways that did not simply support local political efforts but "played a critical role in transforming the Black Arts Movement into a social movement with a mass base" by working "to maintain a dialogue with the residents of South Los Angeles."# But, perhaps ironically, this type of community dialogue has been quite difficult to achieve for black artists working in film, particularly if they are resisting its operations as a "mass" outlet and exploring its possibilities as a means of self-expression.

Thus, "L.A. Rebellion" films present the challenges of black life in Los Angeles self-reflexively, evoking the constant threats to the filmmakers' own artistic practices as emblematic of the perils faced by black creativity in all of its forms. In doing so, these films function not merely as critiques of Hollywood's representational and business practices but as passionate defenses of black imagination as an essential, even if always imperiled, dimension of black humanity.

See Clyde Taylor's The L.A. Rebellion: A Turning Point in Black Cinema, New American Filmmakers Series 26 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1986), and "The L.A. Rebellion: New Spirit in American Film," Black Film Review 2, no. 2 (1986): 9–16; and Ntongela Masilela's "The Los Angeles School of Black Filmmakers," in Black American Cinema, ed. Manthia Diawara (New York: Routledge, 1993), 107–17, and "Women Directors of the Los Angeles School," in Black Women Film and Video Artists, ed. Jacqueline Bobo (London: Routledge, 1998), 21–41. While Taylor's term "L.A. Rebellion" has been used most frequently in scholarship and programming related to these artists, there continues to be much debate about how best to describe this diverse group and their varied works, including different views among the artists themselves. Rather than gloss over these issues, I attempt to leave the contested, constructed nature of naming this group in view by combining and alternating Taylor's "L.A. Rebellion" and Masilela's "Los Angeles School of Black Filmmakers" and leaving these terms in quotation marks.

See David James, The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 320–36; Paula J. Massood, Black City Cinema: African American Urban Experiences in Film (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003); Claudia Springer, "Black Women Filmmakers," Jump Cut, no. 29 (February 1984): 34–37; Monona Wali, "LA Black Filmmakers Thrive Despite Hollywood's Monopoly," Black Film Review 2, no. 2 (1986): 10; and Cynthia Young, Soul Power: Culture, Radicalism, and the Making of a U.S. Third World Left (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2006).

McCullough recalls that "the place where we shot was 115th and St. Peter by the 105 Freeway or something like that where the people had—their house had been destroyed, people had, you know, properties had been sold, and this whole wasteland existed." Perhaps she is referring to South San Pedro Street. Barbara McCullough, oral history interview by Jacqueline Stewart and Jan-Christopher Horak, June 8, 2010, video recording and unpublished transcript, LA Rebellion Preservation Project, UCLA Film and Television Archive.

Masilela, "Women Directors of the Los Angeles School," 35.

Quintard Taylor, In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528–1990 (New York: Norton, 1998), 309, 280.

McCullough oral history interview.

Fellow student Carroll Parrott Blue recalls Water Ritual #1 as "the pee film," and how "everybody got quiet" in response to it at an early screening for black viewers; McCullough observes that most of her colleagues did not discuss the film with her: "I don't think I ever had a conversation with Charles [Burnett] about it. Or Billy [Woodberry] about it. . . . no one ever talked to me about Water Ritual except the women. And that's really been weird." Carroll Parrott Blue, oral history interview by Jacqueline Stewart and Allyson Field, June 23, 2010, video recording and unpublished transcript, LA Rebellion Preservation Project, UCLA Film and Television Archive; and McCullough oral history interview.

Killer of Sheep was restored and blown up to 35mm by Ross Lipman at the UCLA Film and Television Archive and distributed theatrically (and on DVD) in 2007 by Milestone Films.

Elizabeth Jackson, "Barbara McCullough, Independent Filmmaker: 'Know How to Do Something Different,'" Jump Cut, no. 36 (May 1991): 94–97.

Charles Burnett credits Elyseo Taylor for providing students with crucial exposure to postcolonial cinemas: "I think he knew what was going on in film more than anybody else in the department during that period. . . . African films, and things like that, not the art films; everybody knows about that, but about what was going on in the world. Political films, like what's going on in Africa and stuff like that. He brought a bunch of African filmmakers there, which was very interesting." Charles Burnett, oral history interview by Jacqueline Stewart and Allyson Field, June 7, 2010, video recording and unpublished transcript, LA Rebellion Preservation Project, UCLA Film and Television Archive.

Daniel Widener, Black Arts West: Culture and Struggle in Postwar Los Angeles (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2010), 186.