Joe Overstreet

Painter Joe Overstreet spent the early part of his life and career in the Bay Area. His family moved several times between 1941 and 1946 before settling in Berkeley. After graduating from Oakland Technical High School in 1951, Overstreet joined the merchant marine, working part time until 1958. During this time he also did work as an animator for Walt Disney Studios in Los Angeles.

Overstreet began studying art in 1951 at Contra Costa College in Richmond, California. He established a studio on Grant Avenue in San Francisco and trained at the California School of Fine Arts from 1953 to 1954. He was mentored by artists Sargent Johnson and Raymond Howell. Johnson was an especially important model, whom Overstreet admired for his work ethic, keen intellect, and commitment to a black aesthetic. Overstreet became part of the Beat scene in San Francisco's North Beach neighborhood and published a journal titled Beatitudes Magazine from his studio. During the early 1950s he exhibited in galleries, teahouses, and jazz clubs throughout the Bay Area along with James Weeks, Nathan Oliveira, and Richard Diebenkorn, among others.

Overstreet moved to New York City in 1958 with his friend, the poet Bob Kaufman, and set up a studio, designing displays for store windows to earn a living. He studied art and was attracted to the abstract expressionist developments that were happening in the city. He felt his real art education, however, came through his relationships with established artists such as Romare Bearden, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Larry Rivers, and Hale A. Woodruff. In 1962 Overstreet moved downtown and set up his studio on Jefferson Street, in a loft building where jazz musician Eric Dolphy lived.

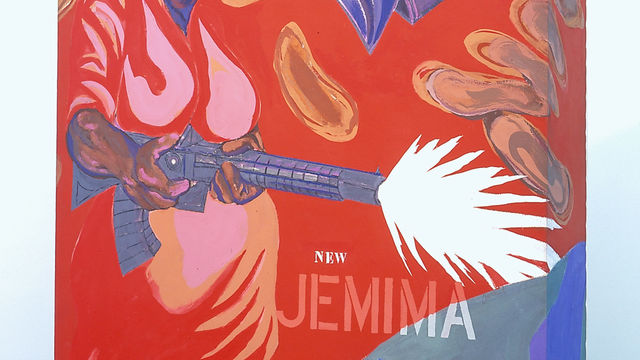

His work from the early 1960s combines geometric and stylistic elements of African art with modernist abstraction and concern for materials. This enabled his desire to fuse a European painting tradition with his search for a black aesthetic, one that considered the status of African art in history and its importance for African Americans. By 1968 Overstreet was sewing canvases that were suspended by ropes. Referring to his paintings, he has said, "My paintings don't let the onlooker glance over them, but rather take them deeply into them and let them out—many times by different routes. These trips are taken sometimes subtly and sometimes suddenly."# In his sculptural rendering The New Jemima (1964), he undermines the popular image of the servile black by presenting the racially iconic figure with a machine gun—a poignant depiction of empowerment.

As did many other African American artists in the 1960s, Overstreet participated actively in the civil rights movement. He organized exhibitions and other projects aimed at creating opportunities for black artists and reaching out to new audiences. He worked as art director of the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School, founded by Amiri Baraka, and developed movable stages that became the model for the Jazzmobile, a citywide traveling program that presented public jazz performances in New York City.

Overstreet went back to the Bay Area in 1970–73 to teach studio art courses at California State University, Hayward. Upon his return to New York in 1974, he met artist Corrine Jennings and writer Samuel C. Floyd. The three established Kenkeleba House, a multidisciplinary space encompassing visual art, performance, dance, and literature. Overstreet organized exhibitions to bring attention to underrecognized master artists, promising mid-career artists, and emerging artists alike. His dedication to art, artists, and the community at large has continued to the present day. Overstreet is still involved with Kenkeleba House through his own work and through the opportunities that Kenkeleba House and the Wilmer Jennings Gallery (the sister gallery named for Corrine Jennings's artist-father) have provided for artists of color.

—Kalia Brooks

Selected Exhibitions

Lamp Black, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1970.

Solo exhibition, Ankrum Gallery, Los Angeles, 1971.

Tradition and Conflict: Images of a Turbulent Decade, 1963–1973, Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, 1985.

Joe Overstreet: (Re)call and Response, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York, 1993.

Something to Look Forward To, Phillips Museum of Art, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 2003.

Rhythm of Structure: The Mathematical Aesthetic, Wilmer Jennings Gallery at Kenkeleba, New York, 2004.

Selected Bibliography

Davies, Carol Boyce, ed. Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2008.

Gibson, Ann. "Strange Fruit: Texture and Text in the Work of Joe Overstreet." International Review of African American Art 13, no. 3 (1996): 24–31.

Lewis, Samella S. African American Art and Artists. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

Powell, Richard J. Black Art: A Cultural History. London: Thames & Hudson, 2002.

Sandler, Irving. The New York School: The Painters and Sculptors of the 50's. New York: Harper and Row, 1978.

Selected Links

Joe Overstreet personal website.

"Joe Overstreet," Rehistoricizing the Time Around Abstract Expressionism in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1950s–1960s.

"The Black Artist: Ishmael Reed, Ortiz Walton, and Joe Overstreet," Pacifica Radio Archives, June 22, 1970.

Tate Modern, "Artist Interview: Joe Overstreet," September 2015.