Houston Conwill

Well known for his ritually charged multimedia installations and performances, Houston Conwill first trained for an ascetic, spiritual life before turning to art. In his late teens he left Louisville, Kentucky, to live in a Benedictine monastery in Saint Meinrad, Indiana.# After leaving the austere monastic environment, he enlisted in the air force (1966–69) during the height of the Vietnam War. By 1970 he had completed his tour of duty and enrolled at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he immersed himself in art, studying with Lois Mailou Jones, Alexander "Skunder" Boghossian, and Jeff Donaldson. During this time Conwill also met the abstract painter Sam Gilliam. Donaldson and Gilliam provided Conwill with divergent examples for the large-scale art practice that would define his later career.

After graduating from Howard with a degree in printmaking in 1973, Conwill, along with his wife and fellow artist, Kinshasha Holman Conwill, moved to Louisville to complete his first major work: a mural and painted-glass commission for his family's church, Saint Augustine.# In the spirit of the times and drawing on the politics of the "black is beautiful" cultural movement, Conwill and Holman Conwill depicted biblical figures as African Americans, a fitting gesture for the church's black Catholic congregation.

On the success of this commission, Conwill entered graduate school at the University of Southern California. Outside of school, he fell in with a group of local artists who shared his interest in politics, including Alonzo Davis of the Brockman Gallery. Conwill joined Davis in the mural group Los Angeles Street Graphics Committee and began to paint socially minded murals throughout the city. This group of artists showed together at the Brockman Gallery and at other venues in the city. Through them Conwill met performance artist Senga Nengudi and became a frequent participant in her performance pieces alongside David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, Ulysses Jenkins, and Franklin Parker.#

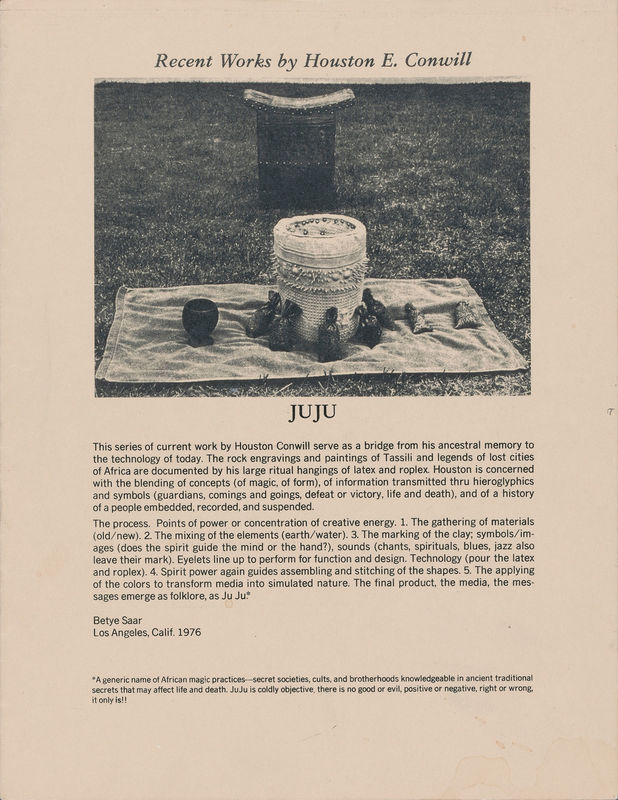

Like many other black artists in Los Angeles in the 1970s, Conwill became interested in African spirituality, infusing it with a personal mythology. As Betye Saar has noted, Conwill conceptualized this fusion under the term juju.# Conwill's engagement with artists' groups in Los Angeles incited a more performative and collaborative edge in his own work, visible in early solo exhibitions and performances such as JuJu (1976) at the Gallery and JuJu III (1976) at the Pearl C. Woods Gallery, where his interest in ritual was first noted.# For the 1980 group exhibition Passages: Earth/Space H3, at the Nexus Gallery in Atlanta, Conwill took his ideas further, into an exploration of death, incorporating actual dirt taken from grave sites into his installation.

That same year he returned to the East Coast, moving to New York and securing a place in P.S.1's studio residency program. His yearlong residency culminated in his first New York exhibition, Easter Shout! (1981), a room-size installation at P.S.1 where he reimagined the Christian rite of Easter as a ceremonial visual and sensorial resurrection. In New York he maintained relationships with artists he had known in California, including Hammons and Nengudi; they all showed their work at the Just Above Midtown Gallery. There, in 1983, Conwill presented Cakewalk, the first iteration of his cosmographic floor installation that tied together contemporary dance, Yoruban and Haitian voodoo rituals, and the American slave practice of the cakewalk. During the run of the show, Conwill staged a performance on the floor pattern working with other artists and dancers in the manner of his Los Angeles collaborations. In 1989 Conwill re-created Cakewalk as The New Cakewalk for a traveling exhibition that originated at the High Museum in Atlanta. For the second version, he broadened the work's original themes, adding in a metaphysical text system and abstract sculptures to redefine the work's conceptual features.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Conwill received significant accolades, including a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowship in 1982, a Prix de Rome in 1984, a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation award in 1987, and commissions for public projects such as Rivers (1991), a terrazzo inlay for the lobby of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York, on which he collaborated with his sister, the poet Estella Conwill Majozo, and the architect Joseph DePace.

—Courtney J. Martin

Selected Exhibitions

Afro-American Abstraction, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, 1982.

Houston Conwill: The Passion of St. Matthew—Painting and Sculpture, Alternative Museum, New York, 1986.

Houston Conwill: Project Series, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1990.

Hirshhorn WORKS 89: Daniel Buren, Buster Simpson, Houston Conwill, Matt Mullican / Sidney Lawrence, Ned Rifkin, and Phyllis Rosenzweig, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., 1990.

The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s, New Museum of Contemporary Art, Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, and Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, 1990.

Selected Bibliography

Lacy, Susan, ed. Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art. Seattle: Bay Press, 1995.

Meo, Yvonne Cole. "Ritual as Art: The Work of Houston Conwill." Black Art: An International Quarterly 3, no. 3 (Fall 1979): 4–13.

Wilson, Judith, "Creating a Necessary Space: The Art of Houston Conwill, 1975–1983." Sculpture issue, International Review of African American Art 6, no. 1 (1984): 57.

Selected Links

Houston Conwill Wikipedia page.

"Cake Walk - A Performance by Houston Conwill," uploaded to Vimeo by UC Irvine Studio Art, April 1, 2016.

Sidney Lawrence, "Houston Conwill: Works" brochure, Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC, 1989.

Sam Roberts, "Houston Conwill, Whose Sculptures Celebrated Black Culture, Dies at 69," New York Times obituary, November 20, 2016.