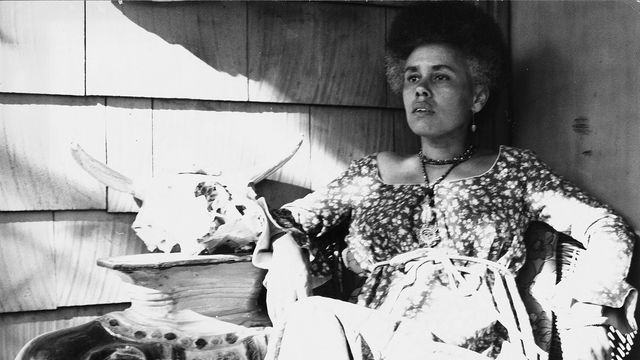

Betye Saar

A pioneer of second-wave feminist and postwar black nationalist aesthetics—whose lasting influence was secured by her iconic reclamation of the Aunt Jemima figure in works such as The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972)—Betye Saar began her career in design before transitioning to assemblage and installation.

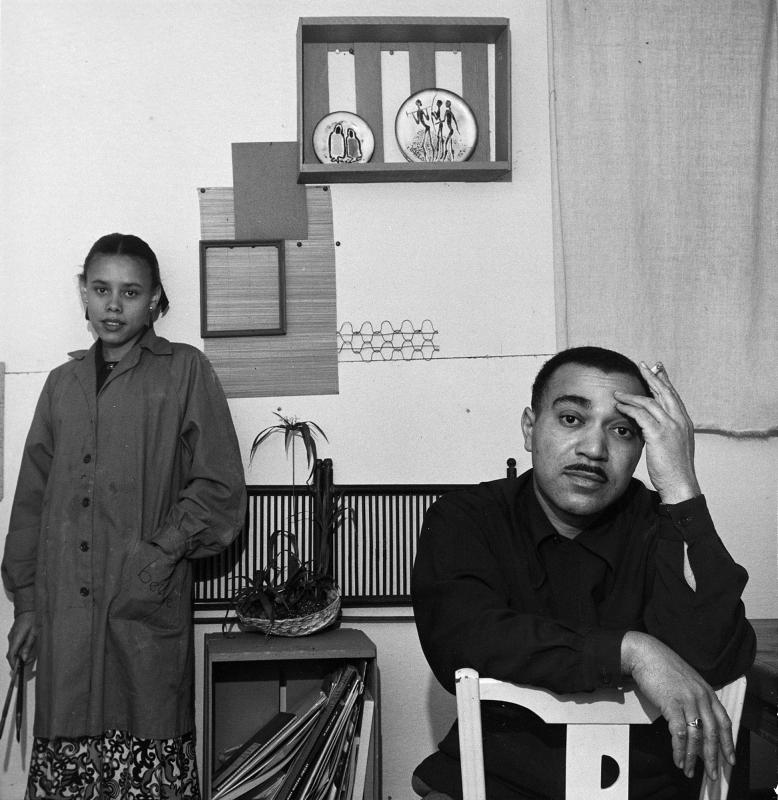

Born in Los Angeles, Saar moved with her family to Pasadena in the early 1930s, shortly before the death of her father in 1931. Pasadena provided a rich cultural and artistic foundation, and she actively took part in arts and crafts classes that allowed her to experiment with a variety of approaches to making objects. Initially a design student at Pasadena City College, Saar transferred to the University of California, Los Angeles, to study interior design. After graduating in 1949, she built an arts community with two recent Los Angeles transplants, jewelry designer Curtis Tann and artist William Pajaud. Later Saar and Tann founded an enamel business, Brown and Tann, that was featured in Ebony magazine in October 1951.

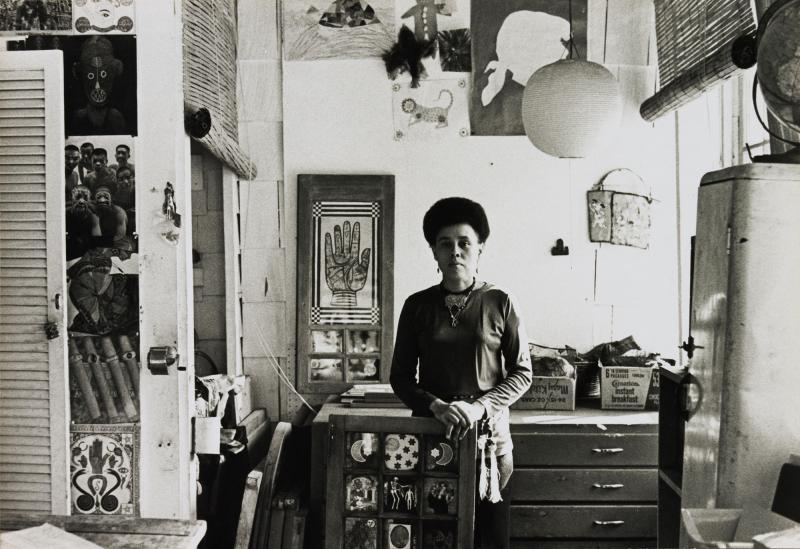

After taking postgraduate courses in printmaking, Saar began creating color etchings, ink drawings, and intaglio prints that shifted her practice away from design into fine art. From these early stand-alone pieces, she began combining her prints with other objects, such as found photographs, or placing them in window frames. Her experiments throughout the 1960s led to her embrace of assemblage, a medium that allowed her to make densely layered works with an equally complex variety of autobiographical and political undertones. Like many of her generation, Saar was deeply affected by the Watts rebellion in 1965 and the death of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. In Black Girl's Window (1969), a significant marker of this moment, Saar uses the window as a formal device to explore the effects of race both personally and conceptually. Cosmological elements (stars, the sun, a crescent moon) and pictorial emblems (a skeleton and a roaring lion, among others) in Black Girl's Window also reflect Saar's turn toward mystical iconography, which she describes as a pursuit of “occult atmosphere” in her work.

After seeing Joseph Cornell's retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1967, Saar too began to encase her objects in boxes and containers that further demarcate their symbolic use. Likened to ritual, Saar's process, and the resulting work, became associated with spiritual practices, particularly those of Africa, Haiti, and Mexico. Though Saar did not travel to Africa until 1977, she and fellow artist David Hammons saw African art at the Field Museum in 1970 while in Chicago for the National Conference of Artists. The connection to other cultures deepened her interest in finding links to a shared universality that could be transmitted by the charge of gathered objects.

Some of these objects were gathered by the artist during trips throughout the world, including Europe, Mexico, and Haiti, or at swap meets and flea markets in Los Angeles. At the latter, Saar collected appalling Americana—negative images of African Americans that she would later reuse in her assemblages. Other objects were personal. As a child she was enchanted with her aunt Hattie Parson Keys's trove of family documents, including photographs. After her aunt's death in 1974, Saar inherited these items and transformed them into assemblages, including Record for Hattie (1975), in which an open case reveals a compartmentalized reliquary of photographs, jewelry, and small tufts of fabric used for quilting. Like much of Saar's work from the decade, memory, nostalgia, and history are conflated with her own personal and familial objects.

The 1970s saw Saar at the center of a vibrant, expansive art scene in Los Angeles that included established artists such as printmaker Charles White as well as younger, more experimental artists who gathered around Suzanne Jackson's Gallery 32 (1968–70). There dance, performance, and craft were incorporated into the program, giving Saar a venue in which to show art with performative and interactive elements. She also became active in the feminist art movement, joining Judy Chicago and others in the female art collective Womanspace. Saar's efforts in making the collective more inclusive culminated in the exhibition Black Mirror (1973), for which she reproduced The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, resituating it as an emblem of the specific racial dynamics of the women's movement. In 1975 Saar's West Coast success took to the national stage with a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, in which she showed intimate collages and assemblages alongside some large-scale altar installations.

By 1988 Saar's stature as an artist was such that she was invited by the U.S. State Department to visit Asia on a cultural mission under the organization of curator E. J. Montgomery. Saar received honorary doctorates from the California Institute of the Arts and Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 1995, and her work was the subject of a major retrospective at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, in 2005.

—Courtney J. Martin

Selected Exhibitions

The Negro in American Art, Dickson Art Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles, 1966.

Prints and Drawings (solo exhibition), Ankrum Gallery, Los Angeles, 1966.

25 California Women Artists, Lytton Center of Visual Arts, Los Angeles, 1968.

Solo exhibition, Multi-Cul Gallery, Los Angeles, 1972.

Solo exhibition, Art Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles, 1973.

Betye Saar, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1975.

Betye Saar, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1977.

Rituals: The Art of Betye Saar, Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, 1980.

Selected Bibliography

Andrews, Benny. "Jemimas, Mysticism, and Mojos: The Art of Betye Saar." Encore American and Worldwide News, March 17, 1975, 30.

Betye Saar. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1984.

Betye Saar: Extending the Frozen Moment. Exh. cat. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Art; Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Carpenter, Jane, with Betye Saar. Betye Saar. San Francisco: Pomegranate, 2003.

Glueck, Grace. "Artists Inspired by the Occult." New York Times, February 16, 1978.

Saar, Betye, interview by Karen Anne Mason, 1996. African American Artists of Los Angeles, Oral History Program, University of California, Los Angeles. Transcript, Charles E. Young Research Library, Department of Special Collections, UCLA.

Selected Links

Betye Saar personal website.

Betye Saar biography at the Roberts Projects website.

Betye Saar Wikipedia page.

"Betye Saar: Mystery," video excerpt from Suzanne Bauman’s Spirit Catcher: The Art of Betye Saar (1977), at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art website.

Kathryn Shattuck, "The Artist Who Made a Tougher Aunt Jemima Hasn't Softened With Age," New York Times, September 12, 2006.

Renee Montagne, "Life Is a Collage for Artist Betye Saar," Morning Edition on KCRW, December 28, 2006.

Getty Center, "Betye Saar Speaks About Her Work" video, March 2011, Pacific Standard Time at the Getty Center, Los Angeles.

Juvenio L. Guerra, "The Ordinary Becomes Mystical: A Conversation with Betye Saar," J. Paul Getty Trust's The Iris, January 4, 2012.

Carolina Miranda, "Betye Saar's Art on Race Couldn't Be Timelier. So Why Aren't More Museums Showing Her Work?" Los Angeles Times, November 12, 2015.

Shelley Leopold, "Betye Saar: Reflecting American Culture Through Assemblage Art," Artbound on KCET, November 13, 2015.

Tyler Green, "No. 222: Betye Saar," Modern Art Notes Podcast, February 4, 2016.

Erin Joyce, "Six Decades of Betye Saar's Personal, Political, and Mystical Art," Hyperallergic, February 26, 2016.

Carolina Miranda, "For Betye Saar, There's No Dwelling on the Past; The Almost-90-Year-Old Artist Has Too Much Future to Think About," Los Angeles Times, April 29, 2016.

Betye Saar, "Influences: Betye Saar," Frieze, September 27, 2016.