Power Up: Sister Corita and Donald Moffett, Interlocking

This essay originally appeared in the brochure for the 2000 exhibition Power Up: Sister Corita and Donald Moffett, Interlocking at the Hammer Museum.

To download the original brochure, click on the Save PDF button at the top of this page.

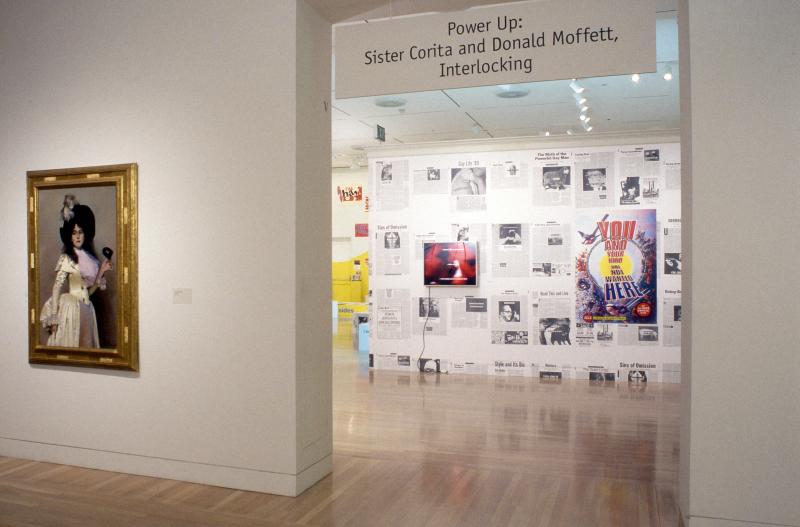

For the exhibition Power Up: Sister Corita and Donald Moffett, Interlocking, organizer Julie Ault has drawn together works by two artists active almost three decades apart, Corita Kent (1918–86) and Donald Moffett (b. 1955). Art created by Sister Corita includes works made between 1959 and 1969 in Los Angeles, while Moffett's works were made between 1989 and 1992 in New York. Though their works differ notably in style and subject matter, both artists employ powerful statements about political and social issues, and both use multiple forms of distribution for their works.

Ault's curatorial presence is not limited to selecting the artists and works for the exhibition. By presenting the works in a context that includes contemporary ephemeral materials as well as her own graphics, colored walls, and modular furniture, Ault has created a new work of art—the exhibition itself. In creating such an exhibition, she reinterprets the traditional curatorial role as artistic practice. As she has noted, curating is a political process as well as an aesthetic act and involves issues of inclusion and exclusion. Her openly subjective approach raises questions about curatorial objectivity and the institutional validation of art and artists through the design and presentation of exhibitions. By extension, Ault also asks questions about the act and meaning of collecting.

Certainly the issue of collecting had much to do with our initial enthusiasm about presenting this exhibition at the Hammer, since the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts holds an extensive collection of works by Corita Kent. Corita made provisions for the bequest to the center of her personal archive of her own work, which includes more than nine hundred limited-edition serigraphs and related drawings and sketchbooks. As both a college teacher and a political activist, she was concerned that this nearly complete representation of thirty years of work be preserved intact within an extensive university art collection available to faculty, students, and the public for research purposes. Corita also recorded an extensive oral history through the UCLA Oral History Program which included a discussion of the intersecting concerns of her life and work: art, education, religion, ethics, and politics. She left her personal papers, photo archive, and remaining inventory of prints to the Immaculate Heart Community, which established the Corita Art Center in 1997.

One of Corita's "rules" for her students was "save everything." In considering the role of a university museum collection such as the Grunwald Center, this admonition seems an appropriate point of departure for a brief discussion of the nature of institutional art collecting. Institutions cannot, in fact, save everything, and their forced selections determine to a certain extent how successive generations view and value art and cultural history. Thus, in making art, collecting art, and presenting exhibitions, we are confronted with a similar range of issues involving personal responsibility, guesses about the nature of the past and future needs, and, inevitably, limitations of time and space.

The Grunwald Center Collection comprises more than forty thousand prints, drawings, photographs, and artists' books, primarily by European, American, and Japanese artists from the sixteenth century to the present. With medium—paper—as the primary principle of selection, graphic arts collections such as the Grunwald Center often contain a wide variety of materials. As with other "special collections" in research libraries and archives, only a fraction of the holdings comes to public view in exhibitions. These collections typically range in date and place of origin from early Renaissance Italy to present-day Los Angeles or Mexico City and in type from one-of-a-kind drawings to mass-produced prints. The latter works might take the form of sixteenth-century "posters" intended to be pasted on city walls, eighteenth-century broadsheets, or illustrations for modern journals and newspapers. Their ephemeral nature and often-inexpensive materials ensure that what was once plentiful, and hardly "collectible," is now rare. The growing interest—in both academic and museum circles—in what is often referred to as "visual culture" has also enhanced the intellectual and monetary value of such materials. But the question of what to collect—given limitations of time, space, and funds—remains a complex one. What most accurately represents a culture: a modest book of illustrated homilies, a broadsheet about a notorious trial or treaty, a sketch for a connoisseur, or an engraving by Albrecht Dürer?

Included in the Grunwald collection are a large number of works by artists who created political and social satire, most notably the nineteenth-century satirists Honoré Daumier and George Cruikshank. The Corita Kent archive is part of this tumultuous tradition of social and political art. This area of collecting is a particular strength of the Grunwald Center and is especially appropriate to a collection belonging to a university where history, politics, and culture are examined in detail from a variety of perspectives.

In the study of art history the print medium offers perhaps the most direct information about social and political circumstances. Such works are often produced for a popular audience familiar with the social and political events of their time. Once available in great numbers and widely distributed, they are today relatively scarce, but their meaning, so enmeshed in the contemporary, is perhaps even more elusive. The biting social commentary embodied in such works is often transitory, based as it is upon ever-evolving current events. The elaborate caricatures that satirized the unfolding events of the French Revolution, for example, portray persons and incidents well known to every French citizen in the 1790s. The biting specificity of those prints, however, presents an enormous challenge for those trying to understand those events today. Similarly, the works of Kent and Moffett will one day be less comprehensible to the average viewer than they are to those of us who are familiar with the historical and cultural milieu in which they were created. Both artists employ a kind of vernacular, often derived from the mass media, which makes their work accessible to a broad audience. But this also "dates" the work, clouding its meanings for later audiences unfamiliar with this shorthand language. Thus, our role as an institution involves not only collecting, preserving, and exhibiting but also undertaking the research and documentation that enable us to respond to a constantly shifting demand for sophisticated historical context.

What to collect, and how to present and interpret it, remains the challenge and the question for institutions. Some, usually libraries or archives, strive to cast as wide a net as possible. The Bibliothèque nationale in Paris, for example, collects one impression of every print published in France as well as all newspaper photographs. Smaller collections, such as the Grunwald Center, cannot be so comprehensive, as the limitations of space and funding demand selectivity. In the case of large gifts, the works have often been preselected. The donation of an individual's collection may represent a lifetime of idiosyncratic searching and selecting. Or an institution may acquire an artist's personal collection of her own work.

The accessibility of a collection allows it to be viewed by individuals or, as in the case of Power Up, juxtaposed with the work of another artist of equal passion but different sensibility. We welcome this opportunity to reconsider our assumptions about our collections and our responsibilities and to recontextualize the works in our care so that they remain an active part of today's cultural and artistic dialogue.

This essay originally appeared in the brochure for the 2000 exhibition Power Up: Sister Corita and Donald Moffett, Interlocking at the Hammer Museum.