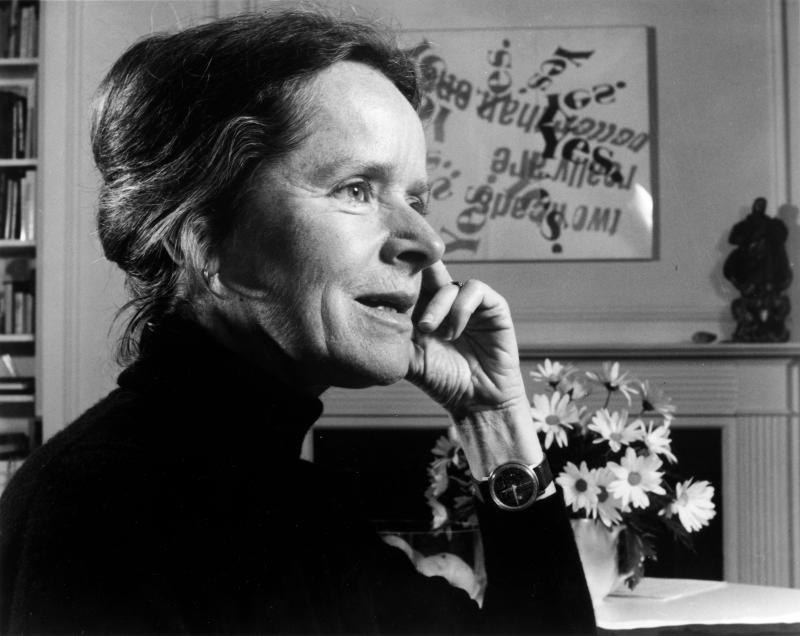

Corita Kent

Corita Kent was born Frances Elizabeth Kent on November 20, 1918, in Fort Dodge, Iowa. Corita, as she would later be known, was the second youngest of six children in a traditional Catholic family. Shortly after she was born, the family relocated briefly to British Columbia, then to Los Angeles, where they remained. Her decision to enter the Immaculate Heart of Mary (IHM) religious order at eighteen was surprising to many of her friends, as Corita had apparently never spoken of becoming a nun, but not an unusual choice for a Catholic girl of limited means. Joining a religious order gave her the opportunity to pursue art and higher education in a way that would not have been an option for many women in 1936. As a member of a teaching order, Corita taught elementary school in Los Angeles while pursuing her BA at Immaculate Heart College (IHC). In 1947, she was selected to join the art department faculty at IHC. She concurrently attended the University of Southern California, studying art history for her master's degree. Many notable Los Angeles artists attended Corita's classes at IHC, including the designers Jan Steward and Gere Kavanaugh, and Self-Help Graphics founder Sister Karen Boccalero.

Corita largely taught herself printmaking through her studio practice. Her early work focused on religious subjects, often contained heavy, medieval-influenced figures, and was incredibly dense. Corita layered more colors than was usual, making up to nineteen-color and twenty-three-color serigraphs. In the early 1960s, her work began to change. Pop art was taking hold in Los Angeles, and it influenced Corita. The archdiocese was not pleased by the style of her early work or the attention she was bringing to herself. Representatives from the chancery office had contacted her superiors on numerous occasions criticizing her work and activities at the college. Nevertheless, she began using advertising slogans and imagery and a wider breadth of source material, including song lyrics and popular literature, and incorporating text into nearly every print. Photography became an important part of her process, and she developed an innovative physical manipulation technique to create her stencils. Her work reflected the tenets of Vatican II that her order had embraced—to get closer to the people. Corita fulfilled her vocation to bring people spiritual messages by communicating via the means they knew best. Familiar slogans and campaigns were imbued with a new significance in Corita's work.

After Corita began printmaking in the early 1950s, she quickly became something of a household name. Her work was widely exhibited, at more than 230 shows across the country by the late 1960s. She was on the cover of Newsweek in 1967 and the subject of hundreds of magazine and newspaper stories. She was named a woman of the year by the Los Angeles Times in 1966, and completed commissions for the 1964 New York World's Fair, IBM, and Westinghouse. Her work was acquired by prestigious museums, such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. And yet she remains largely unmentioned in art history texts.

While art historians often cite Corita's gender and position as a nun as reasons she has not fully ascended into the canon of art history, a number of the contributing factors to Corita's undervalued historical reputation involved her own conscious decisions. First was her choice of media. As a child, Corita had shown a proclivity for drawing and painting, but she began experimenting with silkscreen because she felt it would be a good medium to teach pre-service teachers. She continued to silkscreen as her primary medium because it allowed her to easily produce multiples. She chose to print on common materials because it kept the price of her work low and made it possible for anyone to have a piece hanging in their home. She sold her work in galleries but also at the college, in church bookstores, and by mail order to make it easy to acquire.

Corita's relentless pace of teaching, public speaking, art making, service to her order, and increasing criticism from the archdiocese took its toll. In the summer of 1968, she requested a six-month sabbatical. Though it seemed she had every intention of returning, while she was spending time in Cape Cod she decided to seek an official release from her vows. At the time, it was unclear whether Corita would still return to IHC as a professor or take another appointment (she had an offer from Harvard), but ultimately she decided to do neither and dedicated the remainder of her life to her own pursuits as an artist. At the age of fifty, she settled on the East Coast in her own apartment, a first for her. Though she was not selling her work for large sums like many of her contemporaries, after she left the convent she was able to support herself through the sales of her artwork and commissions.

Her work during this period became calmer and more introspective, still carrying a spiritual message but influenced by a wider range of traditions. Corita developed a watercolor practice that heavily influenced her prints and also recalled the gestural quality of her output from the late 1950s. She began to work exclusively with Hambly Studios in Santa Clara, California, as her printer, corresponding largely by mail. She took on a number of public and private commissions large and small, from a US postage stamp to a 150-foot gas tank in Boston. Corita designed business cards and letterhead for local realtors, and advertisements for national campaigns. She took on a number of socially active commissions for organizations like Hands Across America, Amnesty International, the American Civil Liberties Union, and Physicians for Social Responsibility.

Corita made frequent trips back to Los Angeles to visit the gallery her sister ran for her in North Hollywood and her former community, and settled into her life as an independent artist. For the next decade, she set her own schedule, working at her own pace for the first time. In 1974 at the age of fifty-six, she was first diagnosed with cancer. Though she had periods of remission, she eventually succumbed to a reoccurrence in 1986. She died at the home of a friend in Boston on September 18.

Corita's work lives on in the collections of museums around the world. It is enmeshed with the history of Los Angeles, and in the work of artists like Ciara Phillips, Lari Pittman, Pae White, and Mike Kelley, who cite her as influences. The collection of the Hammer Museum is one of the most interesting because of its completeness and the inclusion of many of Corita's preparatory drawings.

—Ray Smith, PhD.

Director, Corita Art Center