Corita Kent and the Language of Pop

This essay from which this excerpt is taken originally appeared in the exhibition catalogue Corita Kent and the Language of Pop. Copyright © 2015 President and Fellows of Harvard College. Published by Harvard Art Museums, distributed by Yale University Press.

To download the full essay, click on the Save PDF button at the top of this page.

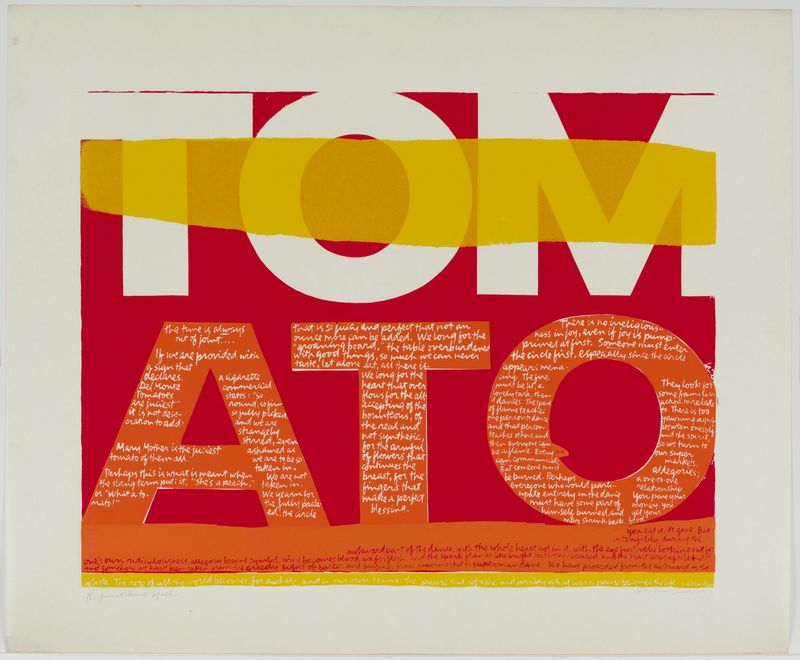

Corita Kent's 1964 screenprint the juiciest tomato of all established her reputation as a renegade. Using red, yellow, and orange ink, she represented the Virgin Mary by spelling out the word "TOMATO," along with the inscription "Mary Mother is the juiciest tomato of them all."# An iconoclastic gesture that dismisses the long history of figurative depictions of the Virgin, the phrase is derived from a Del Monte tomato sauce slogan. Although the provocation of the juiciest tomato was interpreted as a challenge to church authority, for the Roman Catholic artist-nun the print was, to the contrary, an expression of the promised revitalization of church forms and functions by the Second Vatican Council (commonly known as Vatican II). Her depiction of Mary offered an updated conception of female divinity, one rooted in contemporary life and described in current parlance.

Kent's choice of a Del Monte jingle also signaled her affiliation with radical developments in the art world, especially the emergence of pop art. Two years prior, Andy Warhol had made canned goods—including Campbell's Tomato Soup—a much-discussed subject of representation. By making artworks that reference consumerism, Kent not only aligned herself with the mandates of Vatican II, but joined the fray of artists critiquing the ubiquity of commodity culture. While Kent never chose inflammatory language such as "Mary Mother is the juiciest tomato" again, she continued to mine advertising and other popular sources for her work. Although she participated in two heady cultural undertakings—the reformation of religion and art—during the 1960s, she was an outlier in both movements, seemingly, and paradoxically, because of her association with the other.

Kent lived an extraordinary life. She was born in 1918, moved with her family to Los Angeles when she was five years old, and in 1936 entered the Roman Catholic order of nuns of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (I.H.M.) in Hollywood, where she lived, studied, and taught until 1968. Up to the end of her life in 1986, she made nearly 700 screenprints, undertook commissions for public artworks and advertising campaigns, wrote and designed books, produced films, orchestrated Happenings, and created a mural for the Vatican Pavilion of the 1964–65 New York World's Fair.# In 1966, she was one of the Los Angeles Times' "Women of the Year"; the following year she was profiled in Harper's Bazaar's "100 American Women of Accomplishment" and featured on the cover of Newsweek as the exemplar of "the modern nun." Much that has been written about Kent has focused on the exceptionalism of her life and work, including her innovative teaching methods at Immaculate Heart College.# Corita Kent and the Language of Pop looks beyond her remarkable life and pedagogy to examine instead the body of artwork she and her students created between 1964 and 1969, a period of intense engagement with prevailing artistic, social, and religious movements. It focuses on a selection of screenprints, films, installations, and Happenings, as well as Kent's 1971 design for a roadside landmark in Boston, locating these works within their multifaceted art-historical and cultural contexts.

This essay from which this excerpt is taken originally appeared in the exhibition catalogue Corita Kent and the Language of Pop.

Composed by Samuel Eisenstein, an English professor at Los Angeles City College, the inscription was gleaned from a letter he wrote to Kent, responding to the 1964 Mary's Day celebration at Immaculate Heart College.

Images of Kent's screenprints, with complete inscriptions, are available on a database maintained by the Corita Art Center in Los Angeles (corita.org/collection.php). Kent is the author of several significant books and essays that provide insight into her ambitions for her work, as well as the context in which the work emerged. Each is worthy of study in its own right, including Sister Mary Corita I.H.M., "Choose LIFE or Assign a Sign or Begin a Conversation," Living Light 3 (1) (Spring 1966); Sister Corita, Footnotes and Headlines: A Play-Pray Book (New York: Herder and Herder, 1967); and Sister M. Corita Kent, I.H.M., "Art and Beauty in the Life of the Sister," originally published in The Changing Sister, ed. Sister M. Charles Borromeo Muckenhirn (Notre Dame, Ind.: Fides Publishers, 1965), and later in Sister Mary Corita, Harvey Cox, and Samuel A. Eisenstein, Sister Corita (Philadelphia: Pilgrim Press, 1968), 7–26.

In recent years, two significant studies of Kent have been published: Julie Ault, Come Alive! The Spirited Art of Sister Corita (London: Four Corners Books, 2006); and Ian Berry and Michael Duncan, eds., Someday Is Now: The Art of Corita Kent (Saratoga Springs, N.Y.: Frances Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College; Munich: DelMonico Books/Prestel, 2013). Both provide comprehensive biographical sketches. Baylis Glascock's film We Have No Art and Thomas Conrad's film Alleluia, both 1967, offer views of Kent's pedagogy. And in 1992, Jan Steward, a former student of Kent's, published a book of Kent's writings on her teaching methods: Corita Kent and Jan Steward, Learning by Heart: Teachings to Free the Creative Spirit (New York: Bantam Books, 1992).