Gaming Iconography and the Collaboration Between Oliver Payne and Keiichi Tanaami

Walking though Oliver Payne and Keiichi Tanaami’s collaborative exhibition, I was immediately drawn in by the way Payne pulled his iconography from video games, and by the relationship I saw between Tanaami’s work and manga. Illustrators frequently draw from anime and video game references, but it’s still relatively rare to see this niche imagery in fine art spaces. Hito Steyerl did this masterfully in her 2015 video installation Factory of the Sun, but her work functions primarily within narratives of virtual reality, technology, and networks. Her primary point of reference is Metal Gear Solid, a series canonized within gaming as the most important avant-garde work produced by a "AAA" studio, and one of the few that could be considered an auteurial work.

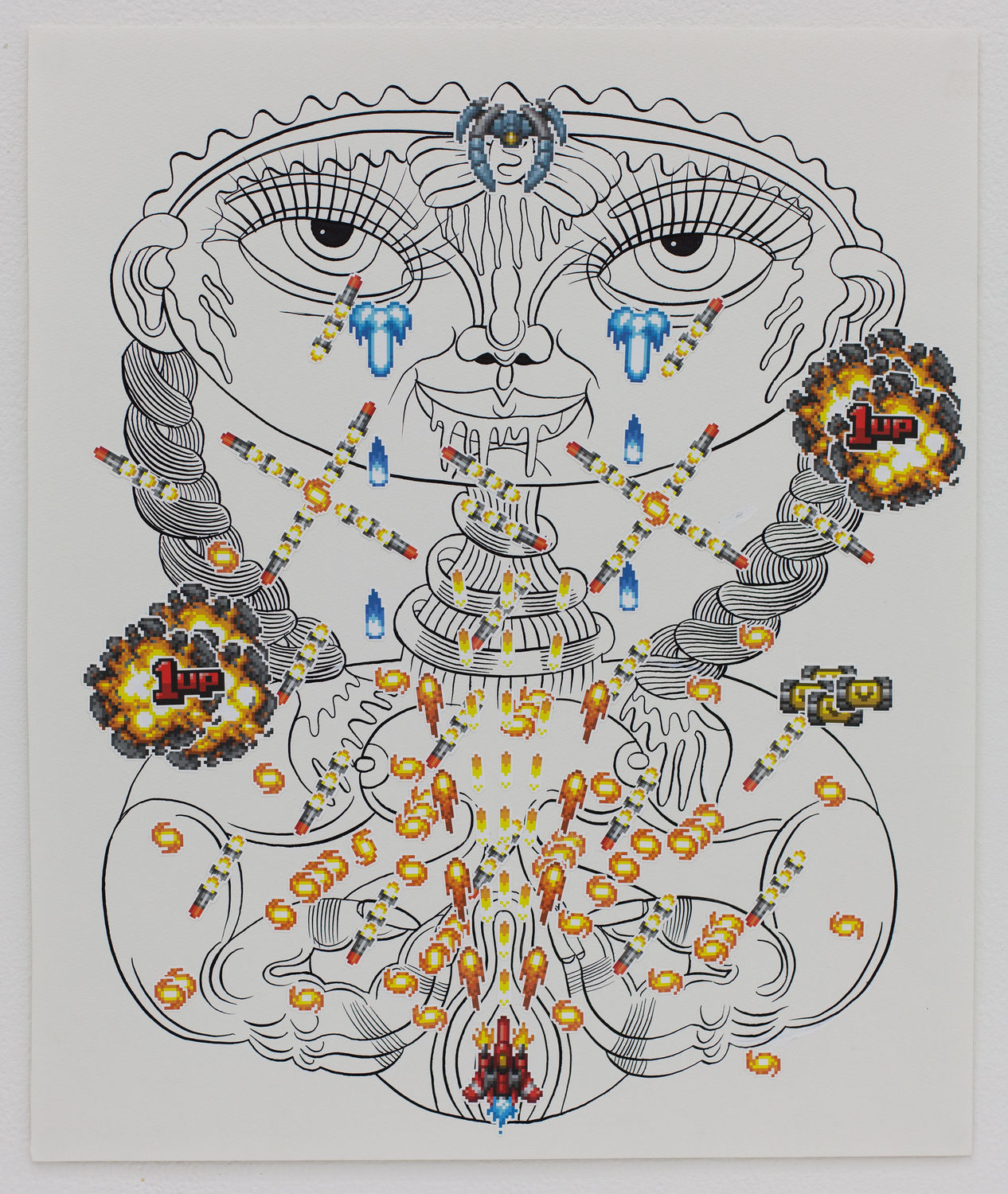

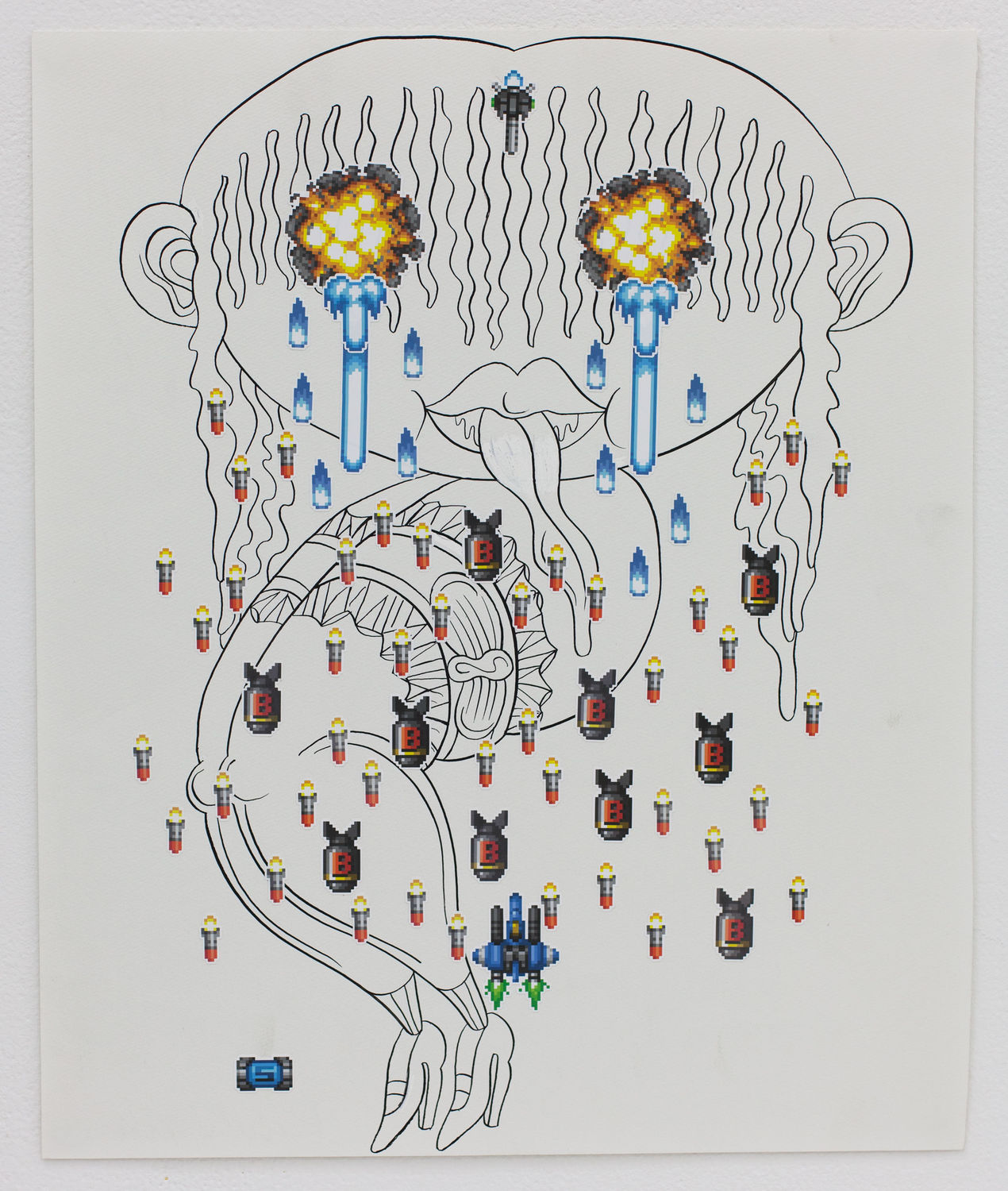

Payne and Tanaami’s work takes a very different approach to its use of gaming iconography and pop aesthetics. They have created a series of static collages—rather than moving images—and the manga-influenced line drawings reference popular culture and folk deities reimagined as leering, drooling, lurid creatures with exposed genitalia. The stickers placed on these drawings are sourced from a largely forgotten, generic, top-down SHMUP (shoot 'em ups). The works contain no narrative about games or labor, no political intrigue. One of the things they do offer us is a "fanboy" approach to art, with Tanaami paying tribute to figures that are powerful or idolized, and Payne reliving gameplay—fantasizing about bullet patterns, intense dogfights, and skillfully defeating a larger, more powerful foe.

It’s this engagement with enthusiast spaces that can make it difficult to perform a close reading of the collages. Particularly, they invoke the perspective of a gamer, which is a type of viewership that is, by and large, deeply invested in escapism and immersion into a set of mechanics or systems. By virtue of this immersion, gamers are insulated from larger cultural or societal questions. Skilled players, in particular, cultivate the ability to ignore information that is not pertinent to the games’ systems. They reduce the colorful sprites to the only meaning they have inside of the game rules: a collection of hitboxes and hurtboxes to either avoid or target. Enemies are not enemies, exactly, but rather understood as a collection of quantitative variables that can include health, damage, speed, rate of fire, and the number of points they are worth. This information is then used to skillfully maneuver through the game, free of distractions or mistaken assumptions that may prove detrimental to a player.

The "hardcore" gamer’s perspective conceals the fact that it is frequently the products of mass consumer culture (in this case, games) that most clearly communicate the economic, social, and political conditions under which they were created. However, by making static works—by removing player control and by recontextualizing the images as a work of fine art—Payne and Tanaami sever the indexical link between these images and the gameplay that they stand in for. This prohibits us from fully immersing ourselves in game systems and internalizing their values, instead opening up space for us to contend more fully with the form of these images and the contexts in which they exist.

Outside of the context of actual gameplay, it becomes clear that the images are ones of horrific violence and war. Tanaami grew up in Tokyo and witnessed its firebombing during World War II, which resulted in approximately 100,000 civilian deaths and nearly 1,000,000 injuries. This and other societal trauma emerge in the obsessive deluge of bombs, flames, and explosions, as well as in the grotesque bodies with exposed skulls, mutated anatomy, mesmerized stares, and tears shed by these bodies. There is no horizon, no landscape, no safe haven or escape. However, neither do the collages entirely neglect the violence or atrocities committed by the Japanese Imperial Army. The figures are twisted, and likely suffering, but they also continue to fire back at the player, dwarfing the player character in both size and capacity for destruction.

Particularly for those of us who were born after these events, it can be easy to forget that the pop culture of an era is not incidental and to become enmeshed in the ideological aftereffects of a moment that we never personally experienced. Payne and Tanaami’s collaboration is a reminder that violence can emerge at the intersection of games and psychedelia, that war and geopolitical trauma can be expressed through play, and that the lowest or most commercial cultural products bear examination alongside the most high-minded ones.