Hammer Projects: Oliver Payne and Keiichi Tanaami

- – This is a past exhibition

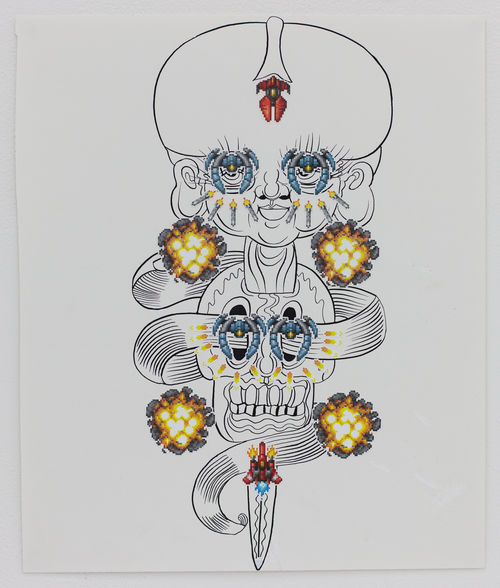

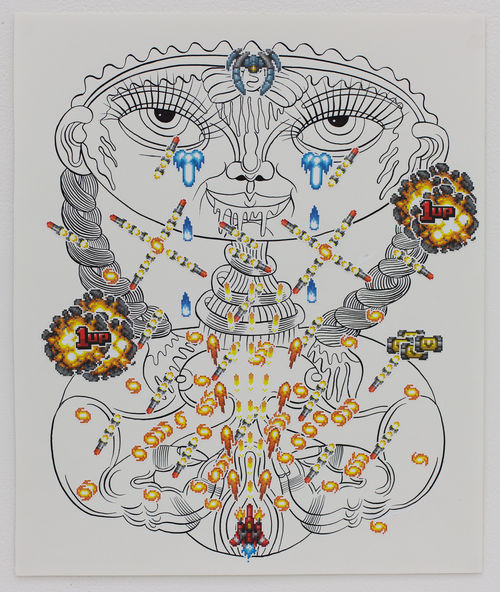

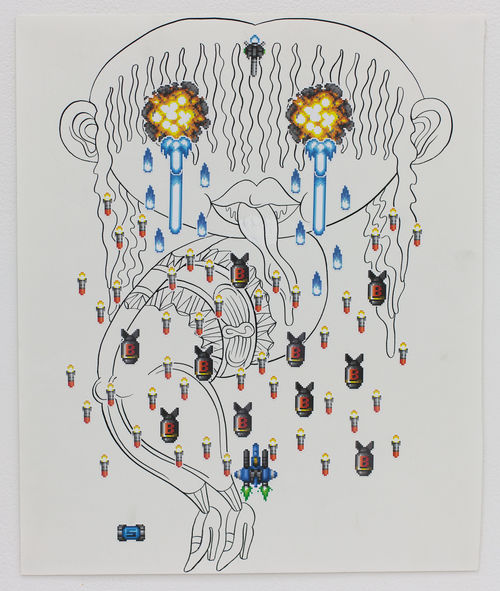

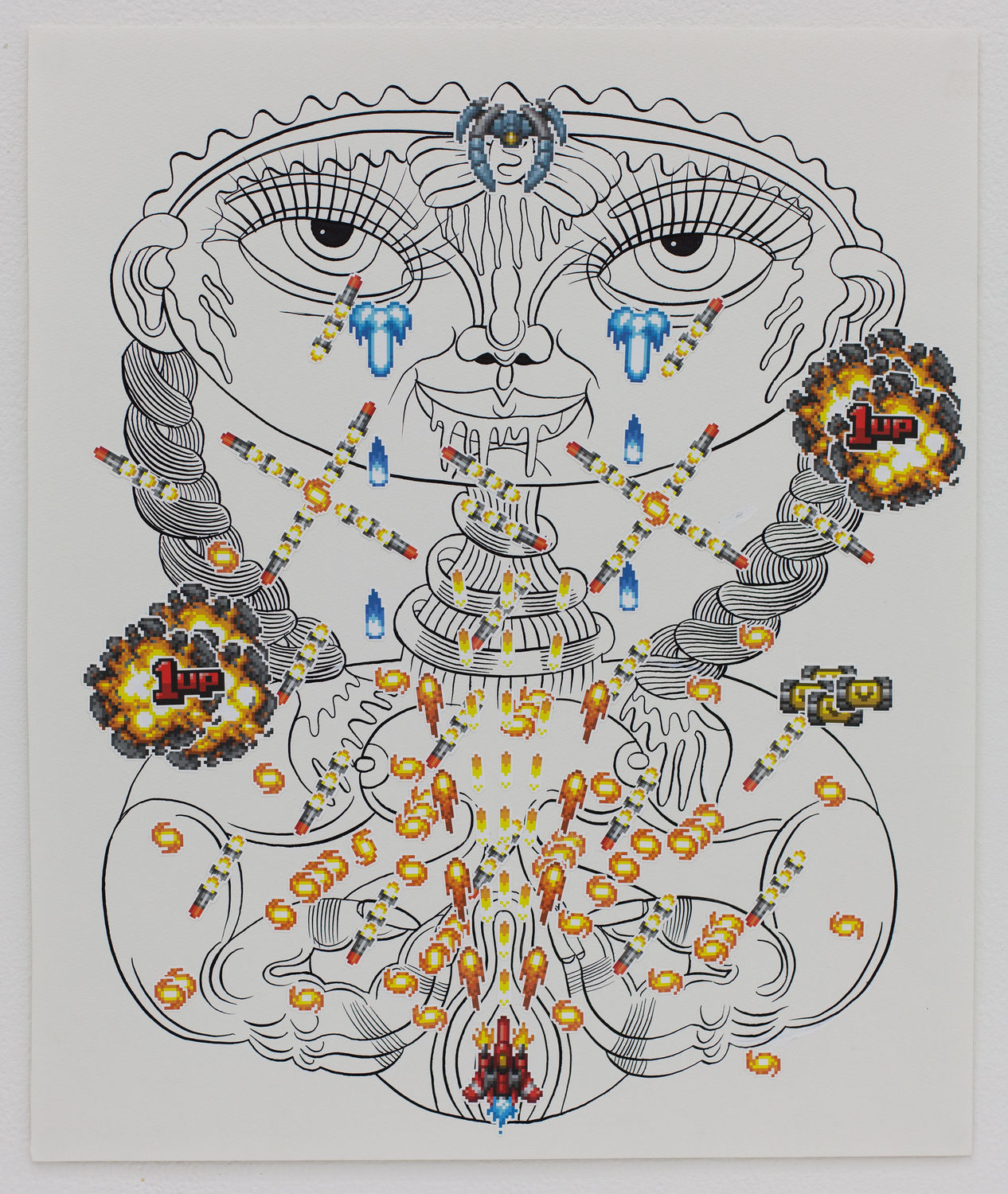

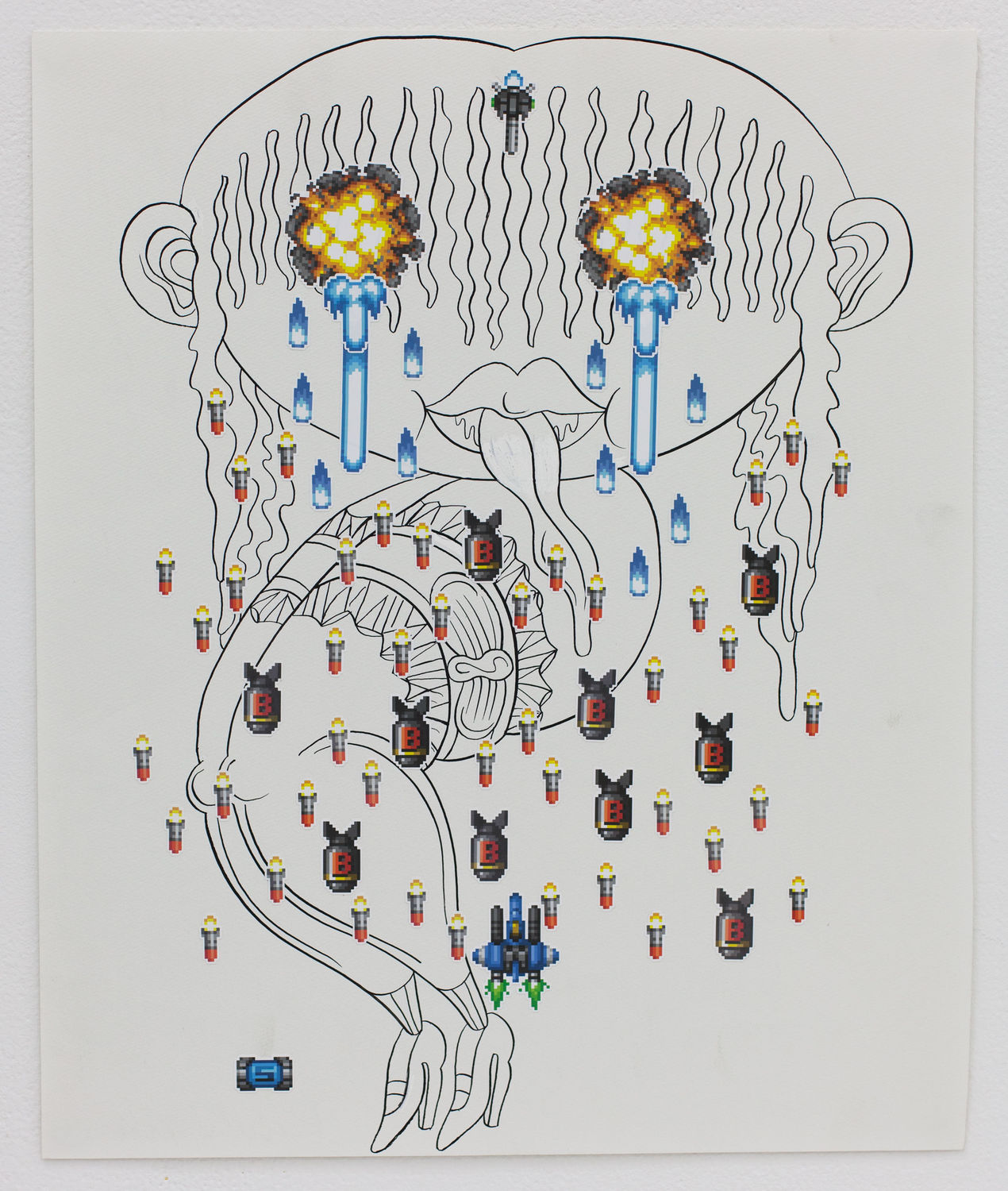

The series of collaborative works by artists Oliver Payne and Keiichi Tanaami represents a world populated by Japanese idols, monsters, and ancient deities set amid icons from popular Japanese “bullet hell” arcade games. In a suite of collages, Payne and Tanaami merge their distinct artistic sensibilities with histories of desire and consumption into a single hallucinatory fantasy. As a progenitor of Japanese Pop art in the late 1960s, Tanaami has been an influential figure in postwar Japan, impacting the ways in which many artists, including Payne, consider their work in relation to forms of popular culture. In particular, Payne focuses on characteristics of video game culture that are analogous to broader social and philosophical concepts. Thus, the collaboration reflects a wider cultural exchange of ideas that Tanaami—as part of an international pop movement—has played an instrumental role in developing.

This presentation marks the first collaboration between the artists. As a true fan, and an artist who organizes his practice through the logic of fandom, Payne holds Tanaami’s work in high regard. Their process began with a series of drawings that Tanaami executed, which became the groundwork for Payne’s meticulous application of bullet hell stickers. The collages bring together two disparate senses of pictorial space and seek to approximate the visual logic of video games. As a recurring theme in his work, Payne considers the processes of art viewership to be analogous to how a player might identify with a given screen.

Much like a kaleidoscopic curtain of distractions in a classic arcade game, the stickers become a scrim through which Tanaami’s drawn figures reveal themselves. The viewer’s eye must, therefore, navigate each image, deciphering the seemingly chaotic array of projectiles, bombs, and other forms of ballistic assault. As much as these works presume a viewing scenario that is upright, horizontal, and wallbound, they are also meant to be read from the orientation of a gamer, who identifies with an avatar at the bottom of a screen as it battles its way upward to the objective of victory.

Hammer Projects: Oliver Payne and Keiichi Tanaami is organized by Aram Moshayedi, curator.

Biographies

Oliver Payne (b. 1977, London) lives and works in Los Angeles. As a duo with Nick Relph, his work has been shown internationally at such venues as Serpentine Gallery, London; Kunsthalle Zurich; and the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Oslo. He has had recent solo exhibitions at Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York; NANZUKA, Tokyo and Hong Kong; STUDIOLO, Zurich; and Galleria Federico Vavassori, Milan.

Keiichi Tanaami (b. 1936, Tokyo) is one of the most influential Pop artists of postwar Japan. He studied graphic design, worked with the Japanese neo-Dadaist Ushio Shinohara, and collaborated with Robert Rauschenberg and Michel Tapié during their visits in Japan. In 1969 he visited Andy Warhol in his Factory in New York and was very inspired by Warhol’s strategy of shifting commercial working practice into art production; he subsequently adopted the hybrid role of artist and commercial graphic designer. He has illustrated record covers for The Monkees, Jefferson Airplane, and more. In 1975 he was announced as the first art director for the Japanese Playboy.

Essay

Oliver Payne and Keiichi Tanaami Interviewed by Niels Olsen and Fredi Fischli

Niels Olsen and Fredi Fischli: To start the conversation, we would like to go back to our first meeting. We remember it very well—I think it was one of our first-ever exhibition projects. When we first met Shinji about six years ago he introduced us to the work of Keiichi Tanaami. The surprising moment for us was when he mentioned your interest in Tanaami’s work—basically that you’re a fan of his! Of course we were already huge fans of your practice and also of your collaboration with Nick Relph. That was such an important influence and reference point for artists of our generation. So then we were curious to call you and ask about your interest in Tanaami.

How did you learn about his work and what made him a hero for you? It all started as this bizarre fan-fan-hero-hero relationship…

Oliver Payne: I don’t exactly recall when I saw the work for the first time. I suppose I was familiar with things like the Monkees and Jefferson Airplane cover art without really acknowledging that they were by him. I worked at MoWax records with Toby Feltwell for a time. During that period I was being introduced to all sorts of absolutely extraordinary art and music from Japan. So I think it was through looking at Japanese books and magazines and listening to loads of Boredoms that I got into Tanaami. A little later I visited Tokyo for the first time and a friend took me to Nanzuka Underground. There I got to meet Shinji Nanzuka and see some Tanaami work up close and get my hands on books of his that were hard to find back home. Seeing all this work blew my mind and basically I became a mega fan.

NO/FF: This idea of being a “fan” of very specific sources is something that I think is very characteristic of your practice. Aspects of your work could be described as “take care” or almost as worship. This is very unusual. Since you often produce series that deal with specific themes, your work has a documentary approach to it. But it never seems distant to its subject—not the “artist analyzing and observing the obscure,” but rather a way of worshipping themes you fully believe in. Perhaps the same could also be said of your series of Japanese bullet hell game collages.

OP: Yes, I’m really into all the stuff I talk about in my work. Video games are something that I’m particularly drawn to, not simply because I love them and play them all the time, but because they are very useful for providing a framework with which to discuss things like space, freedom, identity, labor, play, history, art… all sorts of things. Bullet hell games, a subgenre of shoot-em-up games, are particularly interesting to me because not only are they incredibly beautiful, chaotic, and psychedelic, they also represent a very niche area of hardcore arcade gaming and could be considered to be pure video games. Unlike most popular game genres that borrow from cinema and general current pop culture, bullet hell games are only concerned with themselves and their own, often very complicated, sets of systems and rules. Really, the driving force of these games is “pattern”—the patterns of the waves of bullets, memorizing the patterns of movement through a level, recognizing patterns in the behavior of the enemy boss. And, of course, patterns can be both very pretty and very complicated. So these original works using pages from books of Greek and Roman sculpture are about trying to make something beautiful because of its complexity while still maintaining an inherent logic within the interplay between the bullets and the image on the page. I don’t think I could authentically do this without first really liking bullet hell games.

NO/FF: Keiichi, when you met with Oliver in Tokyo a few years ago you gave him right away forty original drawings to initiate the collaboration. These drawings are defined by black outlines showing very distinct, surreal figures. We wonder what sources and references inspired them? Are they part of your ongoing Dream Diary series, that are persistent documents of your dreams?

Keiichi Tanaami: Each of the forty drawings is not independent; it could be said that it is the same as the drawings made for my recent paintings, consisting of combinations of more than a hundred individual drawings, that is, the materials are to be adopted for different themes. Moreover, the drawings made separately for each theme explore different subjects. Thus, I can hardly explain the forty drawings individually.

Currently, I am working on the book of my Dream Diary, which I have recorded for more than forty years, but the collaboration work with Oliver does not involve records of my dreams. However, dream and recollection are the most important sources of my creation, thereby not totally irrelevant to this collaboration project. The forty drawings instantly selected by Oliver were actually my favorites as well, so I was very happy about that.

NO/FF: It is interesting how you describe your painterly procedure: you collect hundreds of motifs, create an archive, and later on apply them as collages in your paintings. One could argue that the collage is really a core methodology of yours. I’m also thinking about your early collages from the 1960s, where you gather and recombine found images from magazines and advertisements. It’s interesting that you and Oliver found a collaboration in the medium of the collage. For both of you it’s very important as a strategy, but you each apply it totally differently. Oliver is very specific about a source—in this case the bullet hell game elements—and only works with this “one” vocabulary. With a limited vocabulary he then creates rich varieties. You on the other hand use the collage as a way of taking notes, of collecting inspiration from given materials, but also as a way of collecting and documenting your fictional dreams. This very different and paradoxical understanding of the collage within your collaboration creates a great tension.

To come back to your early collages, did they come from graphic design, or how did you start producing them?

[To this question Keiichi Tanaami answered with the following essay.]

KT: “The Brightly Patterned Kimono and the Scent of Kogiku Hanayagi”

I was tidying up at a warehouse in Setagaya one chilly day in 2012 during a heavy rain when I came upon a large stack of paper wrapped in old newspaper.

I had no memory of these dusty old newspapers. When I peeled them open, there appeared more than one hundred brightly colored collages. I had no idea as to how, when, or for what reason this group of works had been made, and though these were unmistakably works of my own, for a moment I could not even fathom why they would have lain dormant here, abandoned in a dark warehouse. I took them back with me to my work studio and, leaving a hurried manuscript, set to work repairing the dried-up flakes of glue and otherwise damaged sections. I carefully scrutinized and verified the stack of collages piled atop my desk, and as I did so distant, blurry memories came back to me, resurrected in vivid colors and stirring up strange emotions.

As I looked at several of the photographs glued onto the background of one collage, a range of scenes I had completely forgotten about emerged.

There is a photo of a local woman in ethnic attire placing a garland of flowers around the neck of a Japanese soldier stationed in Burma during the war: this was most certainly an artificially manipulated photo used as part of a media strategy to cover up the acts of brutality committed by the Japanese army during their invasion of Asia. I had used dozens of these artificially colored photographs as collage material.

A secret pastime of my youth was to quietly look through the enormous, breathing collection of magazines and picture postcards in the closet in our house in Meguro. Printed materials left behind by my uncle, who was killed in the war in Burma, filled up several bookcases that were fitted with fancy doors, and looked like a mountain of treasures to me at the time. The bottom drawer of one such bookcase was crammed with photographs of Germany’s Führer, Hitler, and Italy’s dictator, Mussolini, with whom Japan had formed a Tripartite Pact. There were photos of nude women in gymnastic formation and of nude men, and bizarre picture postcards whose surfaces were covered in embossed swastikas, which you could feel when you ran your fingers over them. As a child, I felt an inexplicable, mysterious sensation and a peculiar sense of excitement. Among these materials, I found myself most drawn to the movie magazine Star, with its large-format covers featuring illustrations of Hollywood stars such as Gary Cooper and Jean Harlow. The various movies glimmering in that space behind closed doors, the dark space and the sharp ray of light penetrating from a small window, were stored deep in my young mind coupled with that distinct setting.

Materials from the Imperial Navy edition of the illustrated magazine Historical Photographs (Rekishi Shashin), which romanticized the Japanese army’s invasion of Asia as a “righteous war,” appear in several of my collages. Alluring movie actresses also became a major element. While I was repairing the collages, the one that stirred within me the strongest sense of nostalgia was a piece that featured a large image of Kogiku Hanayagi. Back when I was living in Nakameguro, the writer Matsutaro Kawaguchi had a house in our neighborhood. It was his so-called second home, where he took up an affair with the geisha-turned-actress Kogiku Hanayagi. Kawaguchi was a popular writer at the time, and the rumor was so well spread that even children knew about it. I loved to doodle, and just about every day I would draw train tracks with pyrophyllite chalk. I drew the train tracks starting from in front of my house and when I got to the front of the Kawaguchi household, the front door opened and there appeared Kogiku Hanayagi, dressed in a kimono. “Little boy, you’re quite skilled,” she said and gently stroked my head, then handed me a confection wrapped in paper. At that moment, the indescribable scent of facial powder enveloped me, and as a child I felt a dizzying sense of sexual attraction. That brightly patterned kimono and Kogiku Hanayagi’s scent—this was my first conscious awareness of the opposite sex. The immense number of films scattered throughout my collages each contain within them an esoteric story, building an alternate world that surpasses the imagination. Countless times during the restoration process, my fingertips came to a full stop and would not budge. The histories told through the photographs along with the material sensation of the thickness of layer pasted atop layer revived memories from within me.

My favorite painters at the time also had an influence on this group of collages, which I believe I made between 1968 and 1970. Still Life with Chair Caning, the first collage made by Picasso in 1912, is composed of an oil painting of a still life, cutouts from printed materials, and straw rope glued around the border of the canvas; this piece was intensely inspiring for me at that young age. I realized that this sort of expression was a possibility, and I can easily say this was the very point, that unforgettable instant, when my stiff, rigidly fixed brain was smashed into smithereens. Another such piece was a collage made by Max Ernst. This mysterious, mystical collage, composed of illustrations from popular novels and mechanical parts catalogues and pictorial plates from science magazines, had a significant impact on my own collage making.

But what inspired me beyond these was the massive inheritance from my uncle piled in the corner of that room. I think it was the murmurs I could hear emanating from the old magazines behind me as I sat at my work desk late at night that moved me to immerse myself in the making of these collages.

My uncle was already past his youthful prime on the eve Japan finally plunged into that reckless war, and the magazines and picture postcards collected during those uncertain times have a special emotional attachment for me.

Hitler’s smirk hidden on the backside of a photograph of a smiling actress and a picture postcard of Hideki Tōjō sporting a comedian’s toothbrush moustache bear witness to that time, and also became important elements that accentuate the meanings of the collages.

The collages contain, for me, a multiplicity of meanings and memories, and today they also seem to present me with a number of questions.

The vast amount of printed material left behind by my uncle was one of the catalysts that triggered me to immerse myself in creating such a large number of collages, and then I remembered another: the cutouts of tropical landscapes and swimsuit photos of foreign women pasted in the college notebooks that my uncle had left behind. These tiny photos, glued on ever so carefully, looked incredible pasted there in the blank margins of pages crammed full of writing.

NO/FF: Another aspect I’m very curious about is how you see “time” as an element in your collaboration. The collages imply a sense of preservation or even archaeology. Of course the antique figures imply the historic, but also the bullet hell game icons speak of passed time, referring back to the 1980s, the beginning of video games. You also explained how difficult it was to collect the stickers and that you even had to reproduce some of them. So in a way the process of producing the collages was almost like archaeology. And now seeing the works today they bring the viewer back to this forgotten time of when video games weren’t yet commercialized, but a culture for a small scene.

OP: Time was a major factor in these works. (And not just the time it took to have the stickers remade.) Specifically the time I would spend on each one to ensure they looked like genuine moments of game play. I wanted them to look as if they are moments from games frozen in time, like screen grabs of a bullet hell game in progress rather than an arrangement of stickers for composition’s sake. When I put down each bullet sticker, it’s not about where that bullet is now, it’s about knowing where the bullet will be in three seconds. Also, having a deeply comprehensive understanding of how these games look was essential and required copious hours of playtime.

NO/FF: The readymade and the “nearly touched found object” could describe many of your works. In your practice you very rarely use craft or production as a tool to create an artwork. At the same time your works have a very strong formal language. How do you decide on the formulation of a work?

OP: This is quite often decided for me, since I tend to work with rule-based systems. So basic parameters and limitations put on a work will sort of tell me “where the pieces go.” That’s certainly the case for the Portal Paintings, Candy Crush Collages, and Weed Container sculptures, for example.

And yes, I mainly work with bought and found objects—weed containers, video game consoles, stickers, arcade cabinet parts, pages of old books. And when craft is required in my work, it’s almost always outsourced to persons far more qualified than myself. Also, it’s worth noting that while I absolutely love bullet hell games, I am terrible at them.

Conversation originally published in Keiichi Tanaami, Oliver Payne: Perfect Cherry Blossom (Zurich: STUDIOLO/Edition Patrick Frey, No. 228), 2017.

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.