Hammer Projects: Avery Singer

- – This is a past exhibition

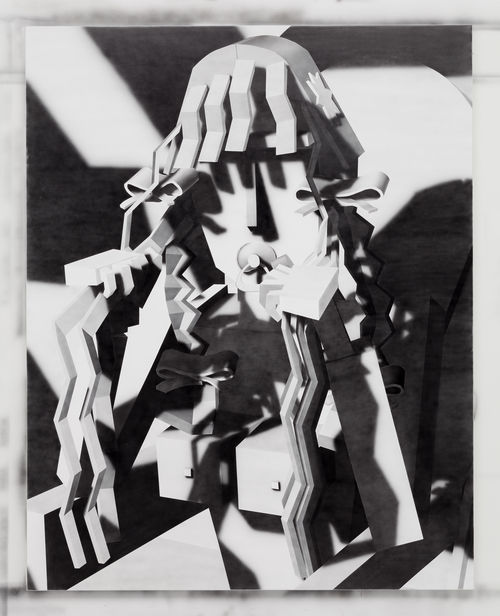

In this exhibition Singer introduces a new suite of paintings that were initially rendered using Blender, an open-source 3-D graphics and animation software program. Employing a visual language in which the handling of shape, contour, and line is largely determined by the program’s limitations, the painted images are the result of a translation from computer screen to canvas. The incompatibility of these two distinct modes of representation forms the basis of Singer’s practice, which has evolved with this body of work to include a distinctive application of color, a new technical means of image making, and a continued pursuit of painterly techniques that simulate the overlaying of visual data on a two-dimensional plane. By using a vector-based program to construct her scenes before they are translated to canvas, Singer creates a world that is resolutely analog while conveying the sense of limitless space and the illusion of depth that have defined the evolution of moving images.

Hammer Projects: Avery Singer is organized by curator Aram Moshayedi with MacKenzie Stevens, curatorial assistant and January Parkos Arnall, curatorial assistant.

BIOGRAPHY

Avery Singer (b. 1987, New York, NY) received her BFA from The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in 2010 and currently lives and works in New York. Recent solo exhibitions of her work have taken place at Foundazione Sandretto de Rebaudengo, Turin (2015); Kunsthalle Zürich, Zürich (2014); and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin (2013). Singer has participated in the 13th Biennale de Lyon, Lyon, France (2015); “2015 Triennial: Surround Audience,” New Museum, New York (2015); and the 6th Glasgow International Festival of Art, Glasgow, Scotland (2014); in addition to group exhibitions at the Hessel Museum of Art, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York (2015); Kunstverein Hannover, Germany (2015); Arizona State University, Tucson (2015); and Kunsthalle Fridericianum, Kassel, Germany (2013). Singer’s exhibition at the Hammer Museum is the first solo presentation of her work in the United States.

Essay

By Aram Moshayedi

Avery Singer’s paintings evoke the tropes of ritual and social patterns that constitute the functions of a curator, artist, or writer at work in the art world today. In The Studio Visit (2012), two figures are seated in front of an array of grossly typical modern artworks—a Noguchi-like sculpture and a constructivist assemblage among them—as they discuss, pontificate, interpret, and explicate amid mute objects and images. The scene is familiar in its awkward rigidity. It’s a situation in which the artist speaks of meaning, the writer speaks of context, the curator speaks of modes of display, the gallery director speaks of value, and the collector speaks of status.

Avoiding contour and subtlety, Singer’s paintings have tended to most often depict blocky, chunky bodies teased out of SketchUp software. More recently, the artist has attempted to exploit the possibilities of Blender, an open-source 3-D graphics and animation program, to create a visual language in which the handling of shape, contour, and line is determined largely by the program’s limitations. The software serves as a means through which Singer is able to sketch out paintings before committing them to physical materials, and her images are the result of a translation from computer screen to canvas. The incompatibility of these two distinct modes of representation forms the basis of her larger practice, which has evolved to include a distinctive application of color, a new technical means of image making through applications like Blender, and a pursuit of painterly techniques that simulate the overlaying of visual data on a two-dimensional plane. By using a vector-based program to construct her scenes before they are transferred to canvas, Singer creates a world that is resolutely analog while containing the sense of limitless space and the illusion of depth that have defined the evolution of moving images across projection screens and digital platforms.

Singer’s paintings have been described as cinematic, constructivist in style, and as resembling old photographs or archival documents.(1) Perhaps it’s the largely grayscale palette that she has employed until recently that makes it easy to locate them within a genealogy of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century technologies. It gives the flattened surfaces a false patina, a mistaken sense of datedness, that diverts attention from the fact that they are produced using recent modeling software and sourced from online research. Although Singer’s works often begin with Internet image searches for general categories—for example, “performance art” in Happening (2014)—and are more or less traditionally painted onto two-dimensional surfaces to create the illusion of space and depth, to call them paintings is largely a misnomer. They are as sculptural, filmic, architectural, and performative as they are graphic or painterly.

Rather than offering insight into the dissolution of a specific medium, however, Singer’s work, as she recently stated, is a result of the pursuit of “new possibilities for portraying naturalism.” (2) Programs like SketchUp and Blender allow the artist to create sketches for paintings that are perhaps more real than a painting could ever be, though the content itself seems to have been passed through some futuristic filter reminiscent of 1980s-era video games. In the process, the modernist ideal is turned on its ear, the cubist form is acutely rendered into a parody of itself, and the insider joke of twentieth-century art history is writ large by a malformed and misshapen conceptual gesture that is as much Dire Straits as it is Picasso.

Take Happening again. The scene is all too familiar: an art school studio class, “sketches for paintings” lining the walls of the painted room, students—artists in the making—letting their creative juices (over)flow. A flutist is being painted as he or she poses with instrument poised to mouth. In this canvas the flutist appears twice: as an object inhabiting the creative space of the classroom and as a nearly complete representation on an easel. In fact, the figure seems to appear again and again in Singer’s body of related work. In at least two pictures, Director and Flute Soloist (both 2014), the musician is more a protagonist than a bit player. But in Happening the figure seems to represent the multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary space of modern-day artistic production and education.

Such behaviors and rituals of art are the basis of Singer’s interests, expressed not only through painting but also through a small writing project titled Press Release Me (2013). The work consists of five fictitious press announcements, written as if they were describing one of Singer’s past exhibitions. There are pull quotes from the artist in many of them: “The only brush I dare pick up cleans my teeth.” “My art practice is like a vacant hotel for all the ghosts of modernism to occupy.” “The only baggage this badass Jewess has brought to Germany is her primitive accumulation.” But the shows they describe are the stuff of fabulation. Part Woody Allen, part cheeky postmodern critique, these mini statements pick at the authority of artspeak and the unique language that the art world has come to rely on, presenting Singer as the main object of ridicule. Perhaps it was already obvious, but her satirical writings on art point to how much the format has run out of steam.

There is surely a jaded brand of cynicism at play here, surprising in an artist as young as Singer, but even more, these gestures indicate a critical self-awareness that is a much-needed antidote to the powers and hubris of an inflated art market and a faith in seemingly bigger, better art spectacles. The shame, embarrassment, and pathos that are reflected in Singer’s paintings make us better equipped to accept the failures of art rather than merely to embrace its champions. So much writing about contemporary art today is quick to identify the successes of the age, to establish a new canon of artistic production, but what would happen if ambivalence became a productive force, if art were no longer judged according to a vague and malleable scale of quality? It’s possible that this thinking would open up a far wider understanding of the art world as something other than a milieu in which accumulators of wealth and power can flourish. As things currently stand, the conditions are far too shameful to leave them as they are.

In Singer’s Saturday Night (2011), a bereted artist sits passed out and slumped over a bar with an oversize bottle of wine nearby. Flowing locks of noodle hair stream onto the bar. The scene seems to embody the title of All my favourite artists had problems with alcohol (2005), a woodblock print by the German artist Andrea Büttner, who is evidently no stranger to the relationship between art and shame. Saturday Night offers a typical, reassuring image of the troubled artist cliché that is part of the popular imaginary. Drunkenness is part of the process, a manifestation of creative genius. Drinking too much, perhaps at an opening or a gallery dinner, is for the most part a norm in the world of art; it’s a welcome comfort zone. Again, standing awkwardly, holding a beer or a plastic cup of wine at a reception, engaged in a scripted conversation with another curator or artist—“So, what are you working on?”—the reality of it all (Singer’s naturalism) becomes evident. But as with any other institution, there are internalized codes of conduct that regulate behavior. The potential shame of stepping out of line, even though it’s part of an otherwise decadent cultural sphere, looms large. There’s a fine line between maintaining appearances and upholding one’s reputation as a reckless soothsayer or wild beast. Singer’s Saturday Night makes all this apparent.

Notes

An earlier version of this essay was published in the book Avery Singer (Zurich: JRP Ringier, 2015).

1. Kasia Redzisz, “Painting as Sculpture as Performance,” Frieze, no. 164 (June–August 2014): 172.

2. Avery Singer, “Digital Reflex,” Texte zur Kunst 24 (September 2014): 72.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy, and Robert Soros. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.