Hammer Projects: Mario Garcia Torres

- – This is a past exhibition

In 1968 the Directors Guild of America created the pseudonym Alan Smithee for directors wishing to disown films in which their creative vision had been compromised. In the intervening years, the name has been associated with one of the film and television industry’s most extensive and indistinguishable filmographies. Though less common today as it once was, Smithee is widely regarded as a prolific and legendary auteur, whose collection of flops made by countless filmmakers tells a story of disavowal, shame, the ambivalences of anonymity, and the cultivation of public personae. Mexico City-based artist Mario Garcia Torres’s one-act monologue, written as an imagined tell-all, casts the fictitious director as a central protagonist in a new single-channel video. Performed by an actor whose delivery embodies the internal struggles of a faceless character and filmed using a visual vocabulary inherited from professional keynote lectures, motivational speeches, and the now ubiquitous TED talk, Garcia Torres’s video speculates on Smithee’s fraught biography and explores the complex relationship between artistic work and its audiences.

Hammer Projects: Mario Garcia Torres is organized by Hammer curator Aram Moshayedi.

Biography

Mario Garcia Torres (b. 1975, Monclova, Mexico) received an MFA from the California Institute of the Arts in 2005 and currently lives in Mexico City. Recent solo exhibitions of his work have taken place at Project Arts Centre, Dublin (2013); Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid (2010); Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona (2009); Kunsthalle Zürich (2008); and Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2007). He has also participated in such international exhibitions as the Berlin Biennale (2014); the Mercosul Biennial, Porto Alegre, Brazil (2013); Documenta 13, Kassel, Germany (2012); the São Paulo Bienal (2010); and the Venice Biennale (2007). Garcia Torres’s exhibition at the Hammer Museum is the first solo presentation of his work in Los Angeles.

Essay

Mario Garcia Torres Presents Alan Smithee

By Aram Moshayedi

As of this writing, Alan Smithee has seventy-eight directing credits to his name. Smithee is not an actual person, however, but a pseudonym created in 1968 by the Directors Guild of America (DGA) to allow directors to disown films in which their creative vision had been compromised. With reputations to uphold, names like Kiefer Sutherland, Dennis Hopper, and Michael Gottlieb (of Mannequin [1987] fame) were strategically removed from film credits after the directors pleaded their cases to the DGA. Although the pseudonym eventually fell out of favor and was formally discontinued in 2000, the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) has continued to track an ever-growing list of television episodes, documentary shorts, and films credited to Smithee. The name has also come to be something of an insider's shorthand for a slew of selfreferential, irreverent productions about filmic failure, flops about their very predestination as flops.

The beginning of the end most likely came in 1997, when the release of An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn gave the alias (played by Eric Idle) his first leading role in a motion picture, as "a rookie filmmaker with the unfortunate name Alan Smithee [who] realizes he's an unwitting studio puppet, being forced to make a big budget action film he knows is horrible." (1) Burn Hollywood Burn is a classic tale of artistic intent falling prey to the powers that be, the movie machine consuming the idealistic artist in a hammed-up kitschy movie about the conditions of making movies. But as evidenced by the film's lukewarm reception, Smithee's secrets are far too uninteresting to become the stuff of drama or intrigue, his character far too unassuming to make a compelling protagonist. His story is better left to the shadows of Hollywood. Yet the anonymity that such an alias offers is an escape route that people in other creative industries might envy, particularly visual artists, in a culture defined by (self-) promotion and the demands of publicity. As it stands, the possibilities of anonymous art making in the age of public relations are limited, and Smithee's successes—as a failure— appear to be something of an outlier.

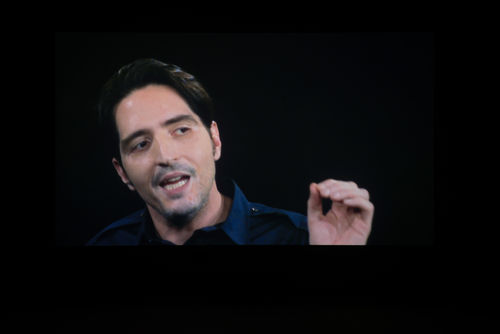

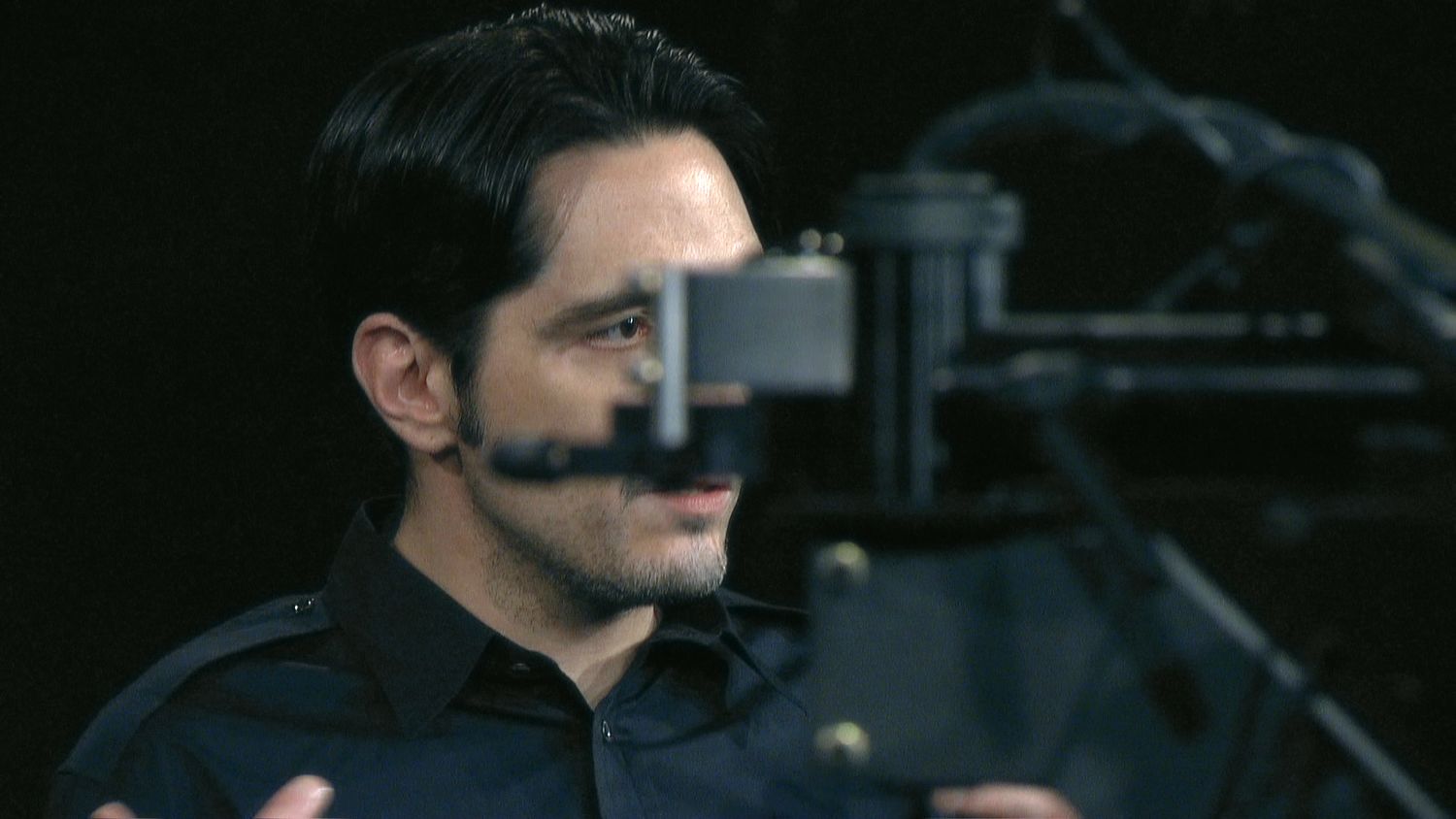

"What's it like to be an alias?" asks the actor in Mario Garcia Torres's one-act monologue titled I Am Not a Flopper (2014). "I'm going to tell you," he continues, as an ensemble of four cameras trace his movements and anticipate his steps over the course of the nearly thirty-minute performance. Based on a live performance that the artist staged in 2007, the video—a documentary approximation of a script coauthored by Aaron Schuster and the Mexico City–based artist and reminiscent of a motivational speech, public-access infomercial, or TED talk—was taped in the television studios of KCET in Burbank. The actor David Dastmalchian, a typecast player of "bad guys," performs the role of Smithee. Appearing to deviate from the script at various moments, he reveals the constructs of this scenario—he was, after all, hired by the artist even though he states that he is "not a front man for Mr. Garcia Torres." He is grateful to the Hammer Museum, but "his opinions don't necessarily express those of his presenters." It's something of an ambiguous role full of doubt and contradiction. Smithee is a text; his words are fed to him by a teleprompter, but his delivery is at times self-aware, as if the persona that he is condemned to inhabit might be overcome by the performer's clever sleight of hand and agency. Though we are led to believe that Dastmalchian is breaking character, he is always staying close to the script.

I Am Not a Flopper is an imagined tell-all that aims to embody the internal struggles of a faceless character, an auteur whose output has been obscured by a history of evasion in which "shame comes up a lot." Anonymity, withdrawal, and failure are all issues at stake here, as the story of a character and the conceptual/political implications of that character's output in one creative field are shown by Garcia Torres to have an analogous relationship to the realm of visual arts. To this end, the actor playing Smithee acknowledges that his filmography has been made by a collective body of talents, which he points out is, after all, a means of production borrowed from the avant-garde.

Anonymity is common enough within the art world today. There are a host of collective identities and alter egos that float around—including John Dogg, Henry Codax, Claire Fontaine, Reena Spaulings, and Donelle Woolford—which don't so much obscure the identities of the participants as serve as fictive cover-ups or body doubles. Along similar lines, most Alan Smithee productions have by now been attributed to a specific person. The use of aliases seems to point toward an insider's conversation, to a consensus within the learned circles of a given industry, even though it's easy enough to decode them with a little sleuthing.

Withdrawal, however, is a harder line to trace. What are historians, curators, and critics to do when someone whose work is defined by its reception willfully disappears from public view? Perhaps a clear enactment of this quandary was embodied by Lee Lozano's Dropout Piece, which the artist initiated in 1970 as an attempt to remove herself from the New York art world. As the writer Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer has recently pointed out, Lozano was not alone in pursuing this impulse, and she cites such examples as Stephen Kaltenbach, Elaine Sturtevant, and Christine Kozlov, who in the 1970s individually removed themselves from the realm of contemporary art in pursuit of alternatives. (2) The fickle art market and the whims of curators and critics often enough make outcasts out of former stars, but an artist's preemptive embrace of failure is a phenomenon unto itself. As Smithee's monologue continues to unfold, it becomes apparent that the faceless character he portrays is advocating not so much for himself as for his filmography. He knows that he can rescue himself only through the existence of a collectively produced and commercially bankrupt body of work. Smithee makes a case for the production of failures as its own creative mode. "I have never met a piece of film I didn't like," he claims, so as to question the well-worn allegation that socalled interesting works have something more to provide than their uninteresting counterparts by way of value. Smithee's monologue seems to appropriately inhabit the space that the playwright Samuel Beckett proposed with the dictum "Fail better," of which Stephen Marche recently wrote, "To fail better, to fail gracefully and with composure, is so essential because there's no such thing as success. It's failure all the way down." (3)

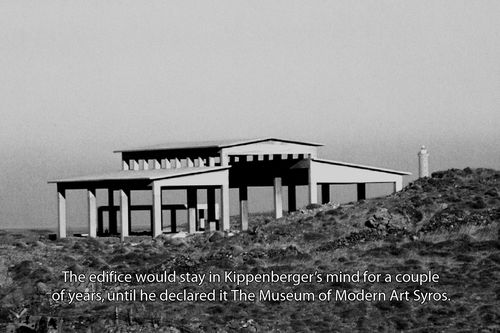

Garcia Torres's works have often considered the validity of the strategies of retreat and withdrawal that have pervaded the history of conceptual art, focusing on such figures as Martin Kippenberger (What Doesn't Kill You Makes You Stronger, 2007); Alighiero Boetti (¿Alguna vez has visto la nieve caer? (Have you ever seen the snow?), 2010); and Robert Smithson (The Schlieren Plot, 2013). In each instance, Garcia Torres allegorizes a so-called minor moment in the artist's biography: Kippenberger's effort to establish a modern art museum on the Greek island of Syros; Boetti's move to Kabul to open the One Hotel as an enclave for artists; and Smithson's time in Texas pursuing the western landscape. These moves from the geographic centers of the art world to its peripheries might be comparable to Lozano's idea of a "total personal revolution," but they also represent something more lyrical, more in line with the secret lives that artists cultivate alongside the demands of their public personae. They are examples representative of the ambiguous line that separates an artwork from everything in the artist's practice that surrounds it, the reason why Lozano characterized her own removal through Dropout Piece as "the hardest work I have ever done." (4)

The artist Christopher D'Arcangelo—another mythic figure that Garcia Torres has addressed in earlier work—created another challenge in this regard, opting in 1978 to remove his name from the announcement and printed materials associated with an exhibition that he was asked to take part in at Artists Space in New York. In D'Arcangelo's case, this gesture of withdrawal would pose a problem for the task of historicizing his practice in the years that followed, while perhaps more poignantly foretelling the young artist's suicide a year later. Forever eulogized in a photographic installation by Christopher Williams titled Bouquet for Bas Jan Ader and Christopher D'Arcangelo (1991), the artist's presence—like that of Ader, who mysteriously vanished at sea—has been marked by his conspicuous absence from the narrative of art history. It is only through such interventions by artists like Williams and Garcia Torres, who directly intervene in the retelling of history in unpredictable ways, that we might be able to account for what the art historian Thomas Crow has called "the fierce reticence of an artist's work." (5) Despite this, an eager public desires—today more than ever—for artists and artworks to be made readily available, never reticent but always on. But this is simply not the way things are.

Like D'Arcangelo, the individual filmmakers who constitute Smithee's identity are a thorn in the side of history and a public eager to consume. The attribution of any clear authorship is denied, and Smithee therefore remains a figure destined for the wrong side of fame and success. His films have been marked as failures before ever seeing the light of day, but they are forced to face this ridicule publicly, as orphans in a sea of big-budget films that depend on the star power of the names associated with them. While Garcia Torres's works have tended more toward the minor, unwritten moments in the history of conceptual art, I Am Not a Flopper touches on an equivalent topic for the entertainment industry as a way of pointing to the moments when the complex relationship between the successes and failures of artistic work and its audiences is confounded. Smithee's is a peculiar story dear to the film industry's imaginary, but as employed in I Am Not a Flopper, it poses a challenge to the notion of allegedly bad films and, more specifically, to what is made visible—or not—in the greater production of works of art.

Notes

1. Mystic80, comment on plot summary page for An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn (1997), IMDb, imdb.com/title/ tt0118577/plotsummary.

2. Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, Lee Lozano: Dropout Piece (London: Afterall Books, 2014), 14–15.

3. Stephen Marche, "Failure Is Our Muse," New York Times, July 25, 2014.

4. Lozano, quoted in Lehrer-Graiwer, Lee Lozano, 18.

5. Thomas Crow, "Unwritten Histories of Conceptual Art: Against Visual Culture," in Modern Art in the Common Culture (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 242.

Hammer Projects is a series of exhibitions focusing primarily on the work of emerging artists.

Hammer Projects is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy, Hope Warschaw and John Law, and Maurice Marciano.

Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley, the Decade Fund, and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.

Special thanks to KCETLink for its support of Hammer Projects: Mario Garcia Torres.