Hammer Projects: Jamie Isenstein

- – This is a past exhibition

Jamie Isenstein often absorbs the persona of inanimate objects (uncomfortably for hours at a time) sitting—or standing or crouching—at the mercy of her art. For her Hammer Projects exhibition, Isenstein presents a work inspired by a story of deceit. At his American Museum (1841-1865), P.T. Barnum placed a sign over an exit door that read "This Way to the Egress." Spectators unfamiliar with the word 'egress' (a term meaning exit) followed the sign expecting to find an exotic bird. Instead they found themselves outside the museum and having to pay another entrance fee to get back in! Barnum's museum visitors' entire conception of what they just saw in the museum was thrown into question. Isenstein explores this "self-reflexive moment of looking and understanding artifice" by taking on the role of the imaginary Egress bird.

Biography

Jamie Isenstein was born in 1975 in Portland, Oregon, and lives in New York. She earned her BA from Reed College in Portland in 1998 and her MFA from Columbia University in 2004. Her performances, installations, drawings, and sculptures have been the subject of solo exhibitions at Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York (2007); Meyer Riegger Galerie, Karlsruhe and Berlin, Germany (2006); and Guild and Greyshkul, New York (2004). Group exhibitions include those at P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, New York; CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco; and Museum Moderner Kunst, Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna. Reviews of Isenstein’s work have appeared in such publications as the New York Times, Contemporary, Art in America, and Modern Painters.

Essay

By Ali Subotnick

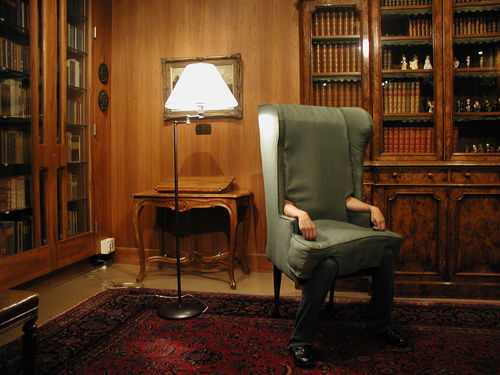

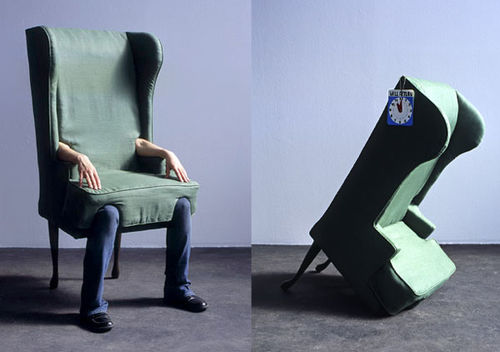

In her exhibitions and projects Jamie Isenstein often absorbs the personas of inanimate objects (sometimes, uncomfortably, for hours at a time), sitting—or standing or crouching—at the mercy of her art. She has transformed herself into a wingback armchair with her legs serving as the chair’s two front legs and her arms as the chair’s arms (the rest of her body hides inside the upholstered chair). In other works she uses herself as a character. For the Performa 05 Biennial she wrote and performed a radio program, Inside Out with Jamie Isenstein, that featured the artist in conversation with her skeleton and a bottle of lotion. The topic of the program: a recent book about plastic surgery’s effect on popular music, using Michael Jackson and Cher as examples. She turns the inside out and recontextualizes the familiar, making us see the world around us in a different light.

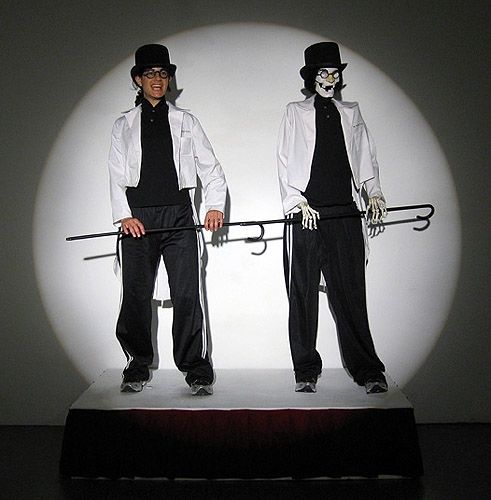

In Infinite Invisible Soft-Shoe (2004), accompanied by a ragtime arrangement of the Bee Gee’s “Staying Alive” on a player piano, thick red velvet theater curtains rise and fall in a ghostly dance on an empty stage set. (Isenstein hides behind the curtains, pulling the cords like a puppet master.) The companion video features the artist and a life-size skeleton—both costumed in tuxedo jackets, top hats, and Groucho Marx glasses and holding canes—performing a soft-shoe dance. Isenstein makes us consider our physicality, anthropomorphizing and animating everyday objects and transforming her body into various inanimate objects.

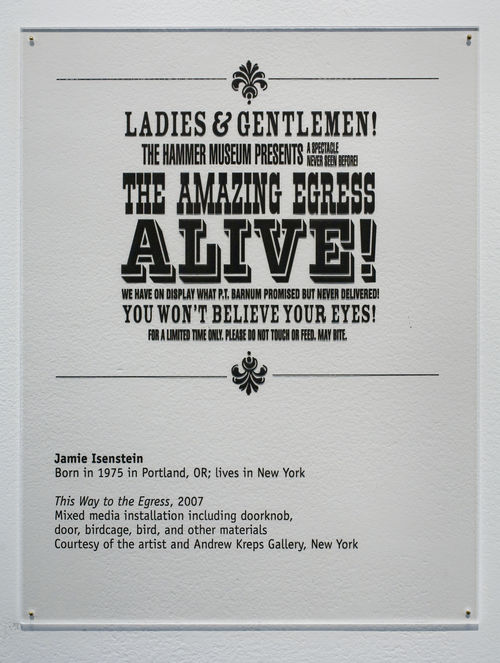

Isenstein’s deadpan acts and objects often draw inspiration from the history of vaudeville, magic acts, and old-time entertainments. Her project for the Hammer Museum is inspired by a story of deceit. P. T. Barnum—the proprietor of Barnum’s American Museum (1841–65), which featured a collection of curiosities as well as natural specimens and live performers—had difficulty keeping his visitors from lingering too long. To solve this problem, he placed a sign that read “This Way to the Egress” over an exit door. Spectators who did not know the meaning of the word egress (a fancy term for exit) followed the sign expecting to see some sort of exotic bird. Instead they found themselves outside the museum (and were required to pay another entrance fee if they wished to get back in). Visitors who followed the “This Way to the Egress” sign and found that a trick had been played on them must have felt that their entire conception of what they had just seen inside the museum had been thrown into question. Isenstein explores this experience, which she describes as a “self-reflexive moment of looking and understanding the artifice of display,” by taking on the role of the exotic imaginary bird. A banner painted in the style of an old sideshow introduces the piece, and inside the gallery several objects add another layer to the mystery. Like notorious tricksters Ricky Jay, P. T. Barnum, and Harry Houdini, Isenstein homes in on our fear of our mortality, and the unpredictability of life, to draw attention to the faith and confidence of the public and their willingness to suspend all disbelief. In the spirit of inspiration the artist responded to several interview questions posed to Houdini in 1904.

1. What was your first performance?

Since I was a kid, and throughout college and grad school, I did many one-night-only performances. The first long-term performance I did was Magic Fingers, in which I sit behind a wall with my hand in a frame. There is a blue background, so the visitor sees the oval frame with my hand in it but can’t see me. I hold my hand in art historical gestures for minutes at a time. Behind the wall I flip through an art history survey book to look for ideas. When I go on break, I hang a “Will Return” sign with a clock to indicate when I will resume the performance. I figured, if art is supposedly forever and if I want to live forever, then I should become an artwork! And if I am an artwork, then I guess I have to do what artworks do, and that might mean sitting in one place for a very long time. Also I was thinking about the definition of sculpture. Since Duchamp, sculpture can be anything, so if you put a living body into the sculpture, is it still sculpture, or is it a performance? This of course led me to the problem of time. I think I’ve figured it out with the “Will Return” sign. Now, with every performance that I do, I make sure there is something in my place to continue the artwork when I am not actually performing the piece. Sometimes it’s an “Intermission” sign or a restaurant “Reserved” sign, but in this case at the Hammer, it’s a “Gone Fishing” sign (since I’m a bird, of course).

2. What was your most difficult feat, the most difficult escape you ever made?

So far the most difficult performance has been Arm Chair (2006). I had to sit perfectly still for hours and hours for a month. All I could do was listen to a recording of Moby Dick. When I emerged from the chair at the end of the day, I felt like I had sea legs, and I kept talking to myself in nineteenth-century sailor speak.

The most difficult escape I ever made was actually quite easy. I took apart a large suitcase and reassembled it inside out so the handle and wheels are on the inside and the lining is on the outside. This made the suitcase into the largest bag in the world. In fact now it is actually holding the entire world because the interface of the lining and the world is complete. So in order to escape from the world, all I have to do is get outside the suitcase (which actually looks like I’m getting inside it).

3. Where do you receive the best treatment? Which people are the most cordial?

It is hard to say. Viewers of Arm Chair in Berlin were quite hands-off, and I found that to be a little disappointing. But the viewers of Magic Fingers at P.S. 1 were too hands-on and that was hard to deal with as well. I was licked on many occasions, I even got a paper cut once, and people placed lots of cigarettes between my fingers. As for cordial, I certainly enjoy Magic Fingers being given a home in a collector’s hallway. Now I can drop in and activate the work indefinitely!

4. Now, don't you exaggerate just a little bit when you are giving your performances? Don't you make it a trifle worse than it looks? And is it a feat of strength or a trick that you resort to?

No, no, no exaggeration! These are difficult performances, especially when I don’t build enough air vents for myself into these sculptures. Then I have to fight to keep from falling asleep.

Ali Subotnick is a curator at the Hammer Museum.