Images of Torture in Videos by Leticia Parente in Radical Women

Throughout the run of Radical Women, we offer weekly gallery talks by artists, scholars, and writers who discuss specific works from the exhibition that inspire and provoke them. In the post below, Myriam Gurba recaps her talk.

"The purpose of torture is not getting information. It’s spreading fear." —Eduardo Galeano

A needle pierces a bare foot. An iron skims close to an exposed elbow. A woman attempts to hang a blouse, and herself, in a closet. These images are among the aestheticized representations of torture, which confront viewers of Leticia Parente’s video art. While the violence in these works unsettles, their ambiguity provokes. Torture is dualistic, a non-volitional dance between perpetrator and victim, but Parente’s work bucks these categories. In her videos, the artist seems to torture herself on behalf of the state, on accident, and while in a state of zombie-like submission. In doing so, Parente mimics the behavior of those navigating, surviving, and dying of Brazilian state-sponsored terror in the 1970s. These videos are experiments in moral theatre.

While their action unfolds in domestic interiors, the videos’ threats of torture summon the specter of the state. Its presence demonstrates the inescapability of Brazilian terror. No safe space exists in Parente’s theatre, not even in the private sphere. Neither the public nor the private sphere, however, serve as Parente’s crime scene. Instead, torture turns the body into its crime scene. American State Department documents chronicling Brazilian abuses in the 1970s are among “the most detailed reports on torture techniques ever declassified.” Methods cited include being stripped naked and made to sit in a dark cell, prolonged electric shocks applied to the feet, cattle prod attacks, and the pau de arara, a punishment once reserved for slaves wherein a victim would be tied and suspended by their arms and legs from a bar. Execution sometimes brought relief from torture. The three Parente videos discussed below feature aestheticized, yet minimalist, reenactments of some of these techniques.

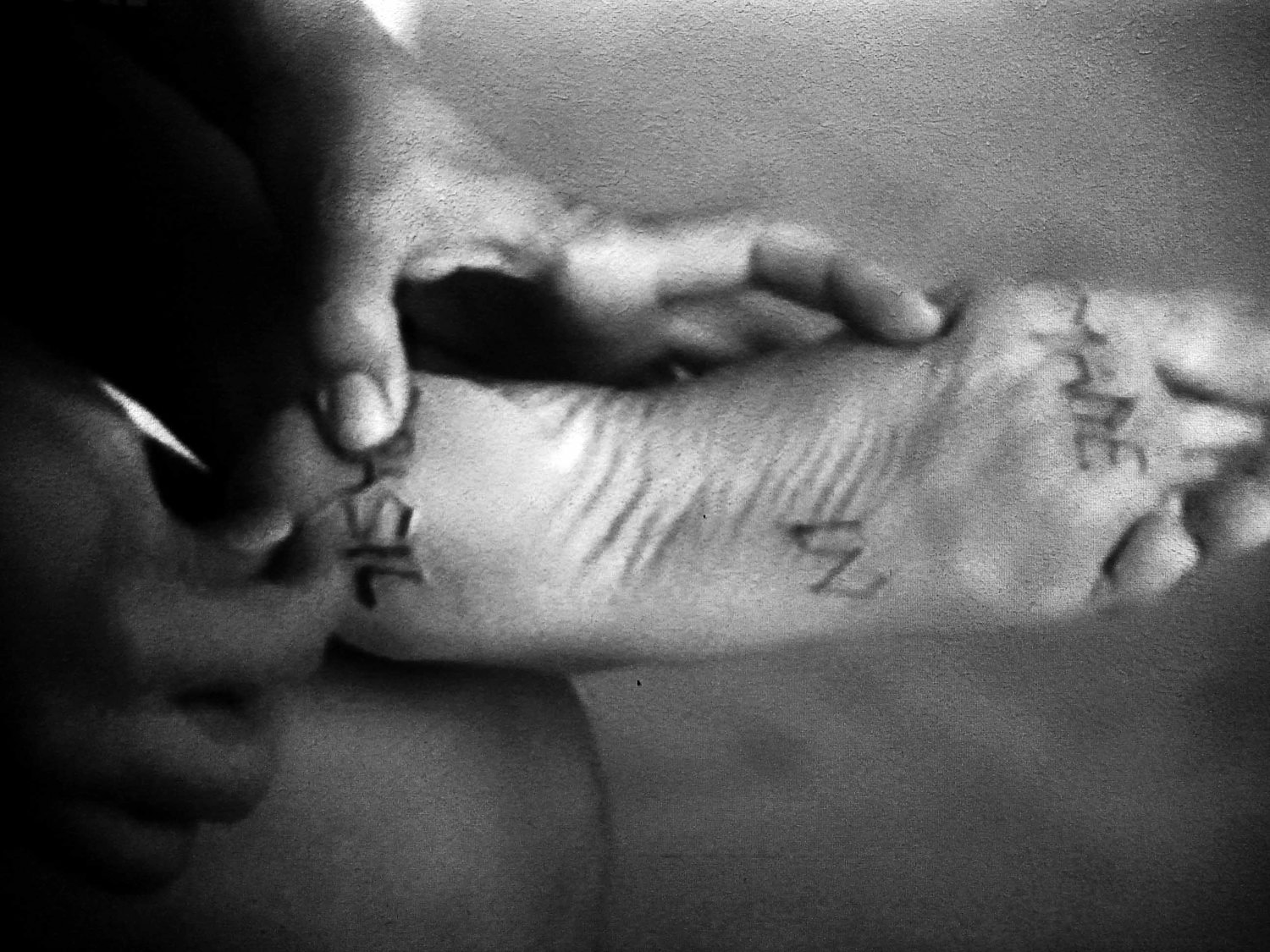

Marca registrada is Parente’s most notorious work. Created in 1975, this silent black and white video opens with a close-up. Bare feet walk to a chair. Hands thread a needle. For the rest of the video’s duration, the needle inscribes "Made in Brasil" into the seamstress’s foot. The seamstress thus becomes a garment, conflating the notions of perpetrator and victim. The bodily location of Marca registrada’s logocentric torture mimics a standard technique used by the Brazilian military in the 1970s—prolonged electrocution applied to the soles of the feet. Needlepoint brands Parente’s skin, turning her sole into an economic broadside, and both form and content tie this work to an even older tradition of Brazilian torture—branding practiced by slave traders and owners. Traders branded slaves on specific body parts to communicate their ownership. Masters branded fugitive slaves with the letter the F. They also severed fugitives’ Achilles tendons, bringing us, once again, to the appendage that abets escape: the foot.

Parente’s work simultaneously alludes to modern branding. A registered trademark popularly associated with Brazil is Volkswagen (VW). Accusations of human rights violations have long dogged VW. In Germany during the Second World War, the company used slave labor culled from Nazi concentration camps to produce vehicles. VW opened its first plants in Brazil on the heels of that war, and Brazilian employees of Volkswagen do Brasil allege abuses that, yet again, tie the brand to state-sponsored terror. Workers assert that during the 1970s, VW spied on its employees and reported suspected subversives to the government. Of his experience former employee Lucio Bellentani said, "I was at work when two people with machine guns came up to me. They held my arms behind my back and immediately put me in handcuffs. As soon as we arrived in Volkswagen's security center, the torture began. I was beaten, punched and slapped."

Subtler violence replaces branding in In, a video from 1975. In features Parente, clad in white, approaching a wardrobe. She climbs into the closet and without removing her blouse, tries to hang the garment from a hanger. Her persistence generates absurd horror. She seems determined, suicidally so, to hang her blouse and, coincidentally, herself. This situational absurdism suggests the execution of journalist Vladimir Herzog. Brazil’s military regime viewed Herzog as an enemy of the state, and on October 25, 1975, in response to a summons, Herzog appeared at army headquarters in São Paulo. Officials detained him. Herzog died while in custody.

Officers issued an autopsy certificate citing suicide as Herzog’s official cause of death. They publicly circulated a photograph of Herzog’s corpse to substantiate their claim. The photograph shows Herzog "hanging from a strip of cloth from the window of the cell in which he was being held…" (Inter-American Commission on Human rights, Report No. 71/15, Case 12.879, p. 20, article 86). The rabbi who handled Herzog’s dead body found evidence of torture, and Herzog’s fellow detainees corroborated that suicide was an impossibility: belts, shoelaces, and anything which could be used to fashion a noose were taken from them. Detainees later testified that Herzog had been made to sit in an electric shock seat. A team of interrogators used an electric prod on him and eventually placed something in his mouth to choke his screams. He likely died during torture. In light of this case, and its timing, In may be read as a commentary on the absurdity of the Brazilian military’s lies surrounding Herzog’s impossible suicide.

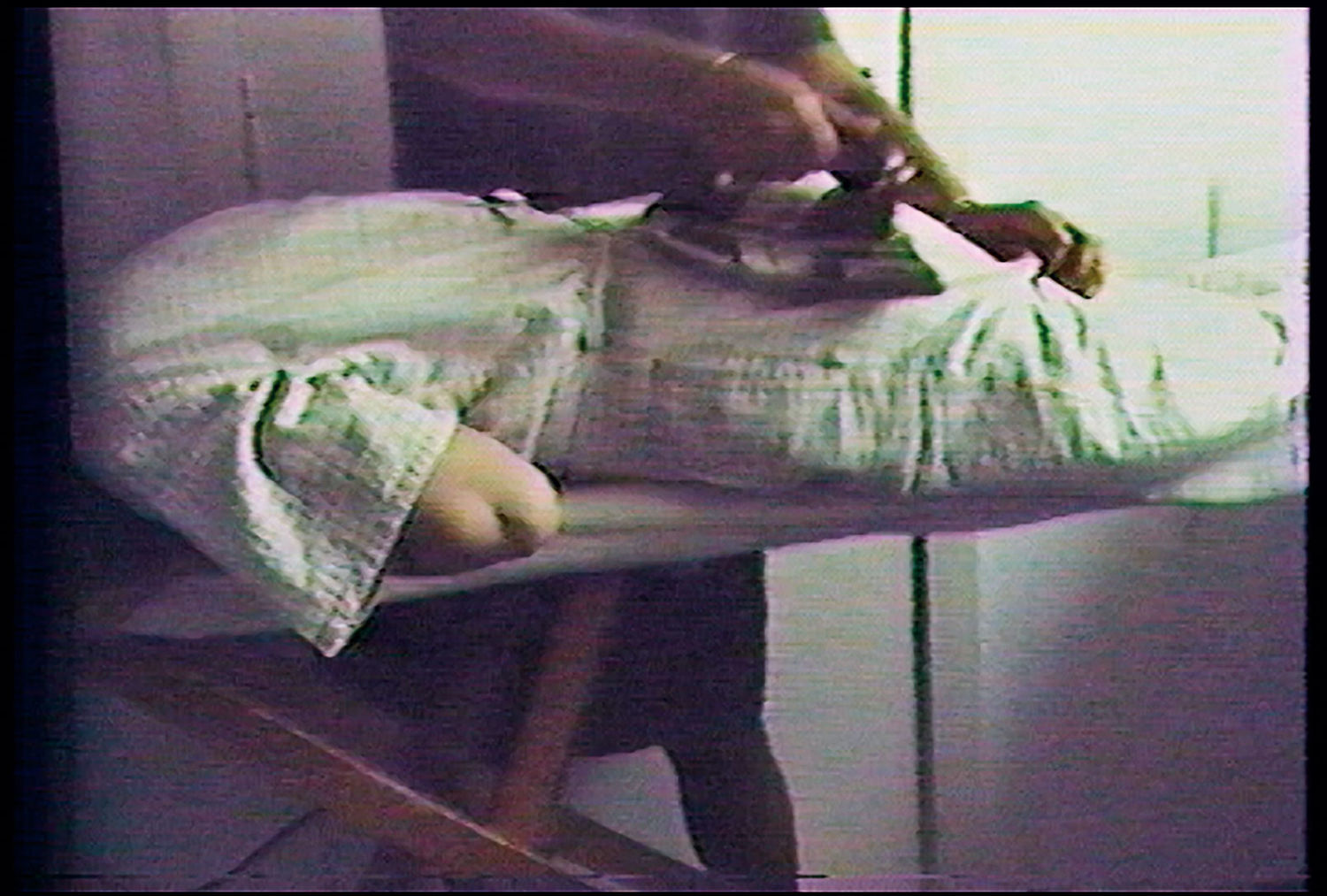

Tarefa I, made in 1982, brings us back to branding. Parente, dressed in white, mounts an ironing board, flattening herself against it. Another woman stands beside her, wielding an iron. The woman proceeds to run the iron across Parente, seeming to iron the artist’s blouse and pants while she wears them. While Marca Registrada is the more famous of Parente’s video artworks, Tarefa I is more sophisticated. The viewer can only guess whether or not the experience is painful: whether or not the iron is actually hot remains unknown. Also, the victim/perpetrator dichotomy becomes even more ambiguous despite the material split between the two. While the woman holding the iron is, upon observation, the perpetrator, the victim courts violence by willingly climbing onto the ironing board. Like an automaton, she submits to the iron’s threat. As it moves across her, she remains very still, balancing her body, keeping still so as to avoid being tortured by a burn. This dance between perpetrator and victim, which is at times a dance with oneself, is rendered through exquisite yet plain visual metaphors.

As democracies around the world weaken, I hope that we can be reminded by work such as Parente’s that the price to be paid for letting them crumble is both painful and high.