Harry Dodge on Jim Shaw's Dream Object

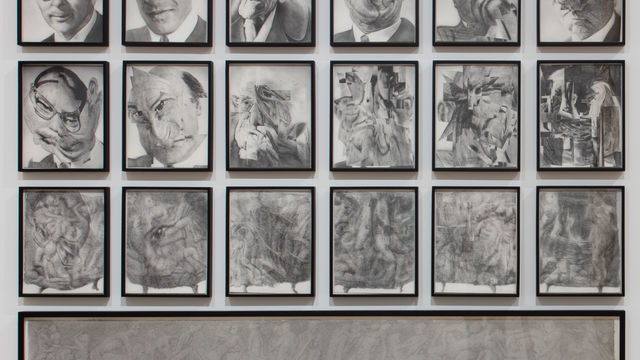

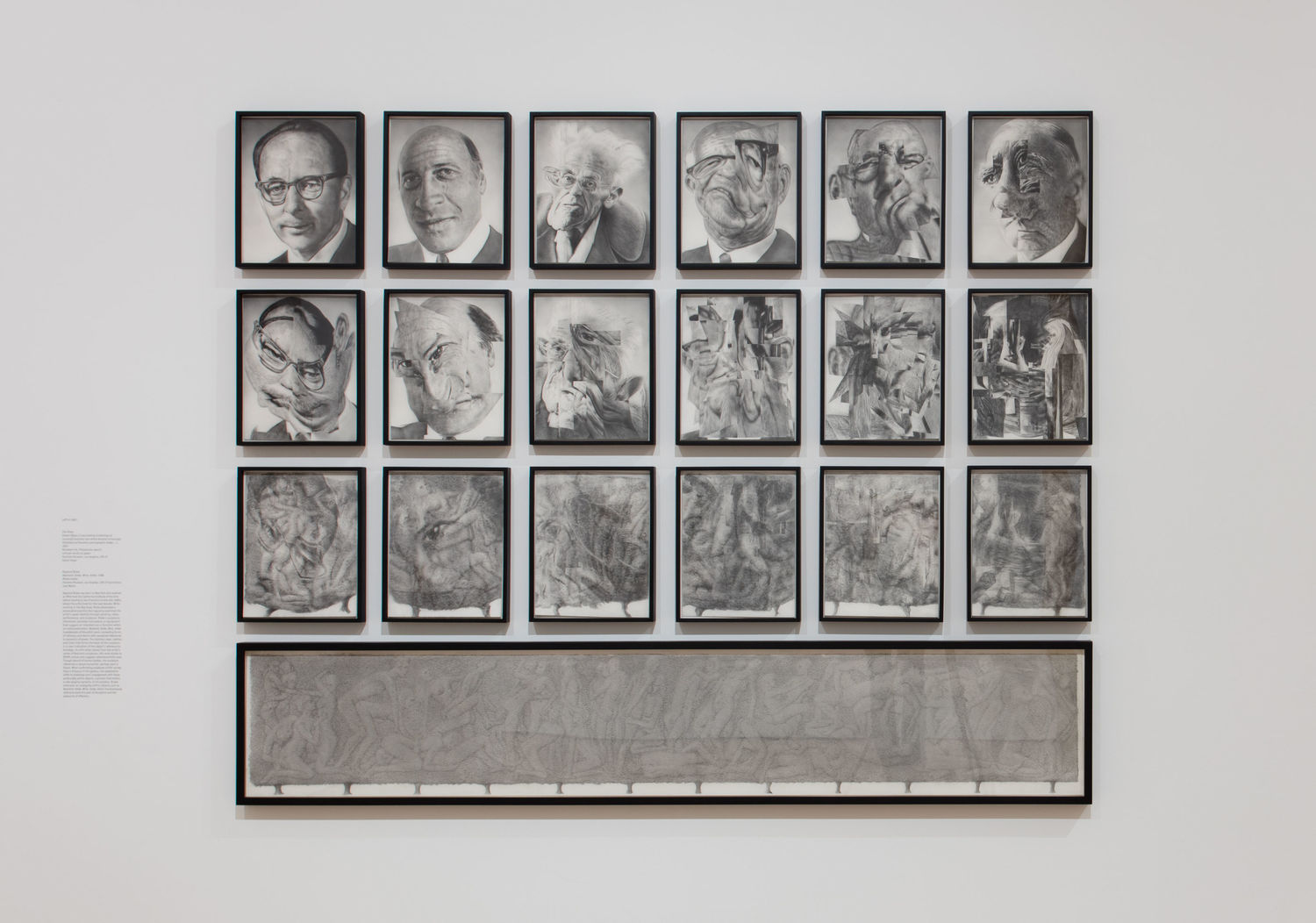

In this video, Living Apart Together artist Harry Dodge discusses another work in the exhibition, Jim Shaw's Dream Object (I was looking at drawings of successful business men which became increasingly distorted and became a pornographic hedge…).

Below the video, read Dodge's full essay on the work.

Dream Object (I was looking at drawings of successful business men which became increasingly distorted and became a pornographic hedge…) is a big, multi-part graphite drawing by Jim Shaw, and in Living Apart Together, it’s sandwiched between Nayland Blake’s erotic restraints piece Restraint: Ankle, Wrist, Ankle and Barbara T. Smith’s Field Piece, a maze of objects that look a lot like giant sex toys. I just love looking at the Shaw near these other ones. These other works pressure the Shaw and, to me, provide a hilarious, sort of wizened challenge to the meaning-making machine in the big drawing, adumbrating or making legible layers that, in another context, might be buried. Bodies are noticeably absent in both the Blake and the Smith for example, and are provided soon thereafter by the Shaw. This interplay of say, absence and presence, for me, conjurs or even materializes a sexual imaginary. The mental part of sex. One could argue that more generally this functions as a salient critique of the myriad ways we devalue the mental, for example, an artists own thinking about their work, the conceptual apparatus, or the way we so often mistake virtual space as immaterial. Nayland’s piece also sort of teases out some of the homosexual/homo-social content in the Shaw, and the Smith suggests that we might even bend these CEOs over and penetrate them—a kind of re-evaluation of corporate power (or the erotics of power in general) and our relationship to it. And since I harbor a biding (albeit complex) critical antipathy to the type of character portrayed in the drawings, I get to revisit that here too. One thing that happens is that the odd, awkward sexuality that is suggested becomes a kind of lighthearted common ground.

I don’t normally like titles that utterly reify what’s apparent in the structure and meat of the piece—but in this case, the title has a deeper sort of comic structure (what Henri Bergson refers to as a reciprocal interference, which is a sort of startling paradox) that does some heavy-lifting in a work which would otherwise (without the title) just be a sort of cheeky performance of drawing ability, almost humdrum in its glib virtuosity. So the title sort of blunts the smugness of the drawing achievement, by a kind of intervention of self-effacement. The self-effacement is mainly a result of velocity; there is, you might say, a quick joke. Something immediately funny is presented. So the title pressures the read, speeds things up, but then when we go to examine the drawing, unpack it visually, this takes place at a much slower pace. For example, we might be looking at the incremental de-evolution of a man’s face, watching it melt say, or crystallize, and we might return to examine a drawing we’ve already seen, make a comparison, before we’ve even cursorily examined the piece in toto—so we get little looking circles, little eddies of attention. This takes time, and that time is at a different scale than the speed at which the humor in the title works. This slow looking lands onto the title’s levity (and brevity), it goes in that order. Creates texture.

In the case of the title, the pornographic hedge would seem to be the prime bounty (sort of like orgasm as a goal in sex) but in checking out this work, we’re much more involved in the kind of distortion that’s taking place with the gentlemen’s faces, crystallization, magnification, swirl, a sort of panoply of treatments drawn from a litany of abstraction techniques which initially refer back to the history of mystification, but then these techniques or treatments sort of come of age, and strike me as effects menus in Photoshop-like computer applications that put mild or extreme visual distortion right at our fingertips. We used to have to go to the fun house mirrors; now we just get on Apple’s Photobooth in order to experience this particular delight.

In the title, Shaw refers to something he calls “Dream Object” which the rest of title explicates in this sort of pugilistic, blunt comic language, like I said. I like the smash-up here, of two words that contrast: dream and object. You have dream, and this is something we think of as immaterial. Dreams are made of thoughts but ghostier, night-time images, you know, stuff we’re not even responsible for, nocturnal interlopers. And then you have “object,” whose meaning is sort of defined by materiality, edges, palpability. Now I, personally, do a lot of thinking through deep materialism—in my own practice this is one of the core questions I’m working through—and I find a great pleasure in inventing and talking about what I call “thought-objects.” Objects made of language, made of thought, which suggests either that language is particulate (and I think it is) or that thoughts are (and I think they are) or both. Shaw evokes all that stuff for me up front here, as a sort of matrix onto which all of the other experiences of this piece fall afterward, like seeds.

Though I profoundly enjoy this work as a mildly transgressive, inappropriately sexual, mildly-comic thought-object, it is worth observing here, that I paid no heed to the details of its most explicit visual offerings. Indeed, I’m not at all sure I even looked at—but most certainly have no memory of—the specific sex acts that are taking place in the all-important pornographic hedge. (Are they gay, straight? Violent, vividly rendered or urgent and sketchy?) It’s enough for me that someone thought of the idea of a “pornographic hedge” and also rendered one. I don’t also need to memorize it. I was making notes for this interview and I had jotted down, pornographic shrub. The comedy in that could feed me for a week. It’s a winner, and touchable to me, palpable as a thought-object. Plus, honestly, a lot of people do have sex in shrubs. I have always thought of wilderness as a real mood-killer myself however—but I guess I could get used to meeting strangers in shrubbery in order to get off. I could get used to it. And then, of course, it would probably stop being funny.