Family Day Workshop Preview: Tanya Aguiñiga

Every year the Hammer welcomes hundreds of our youngest visitors to the museum for Family Day, a free festival-style extravaganza of art, music, improv, performances, and more. Our 7th annual Family Day is quickly approaching—mark your calendars for August 19—and this year’s theme is Art for Good. Every day history is being made, and there is no better time than now to uplift and enable young people to impart good in the world through art and activism.

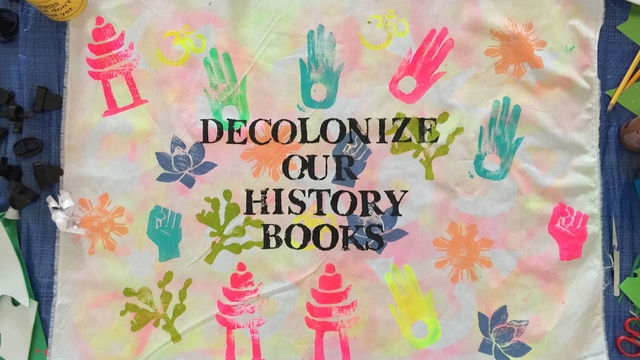

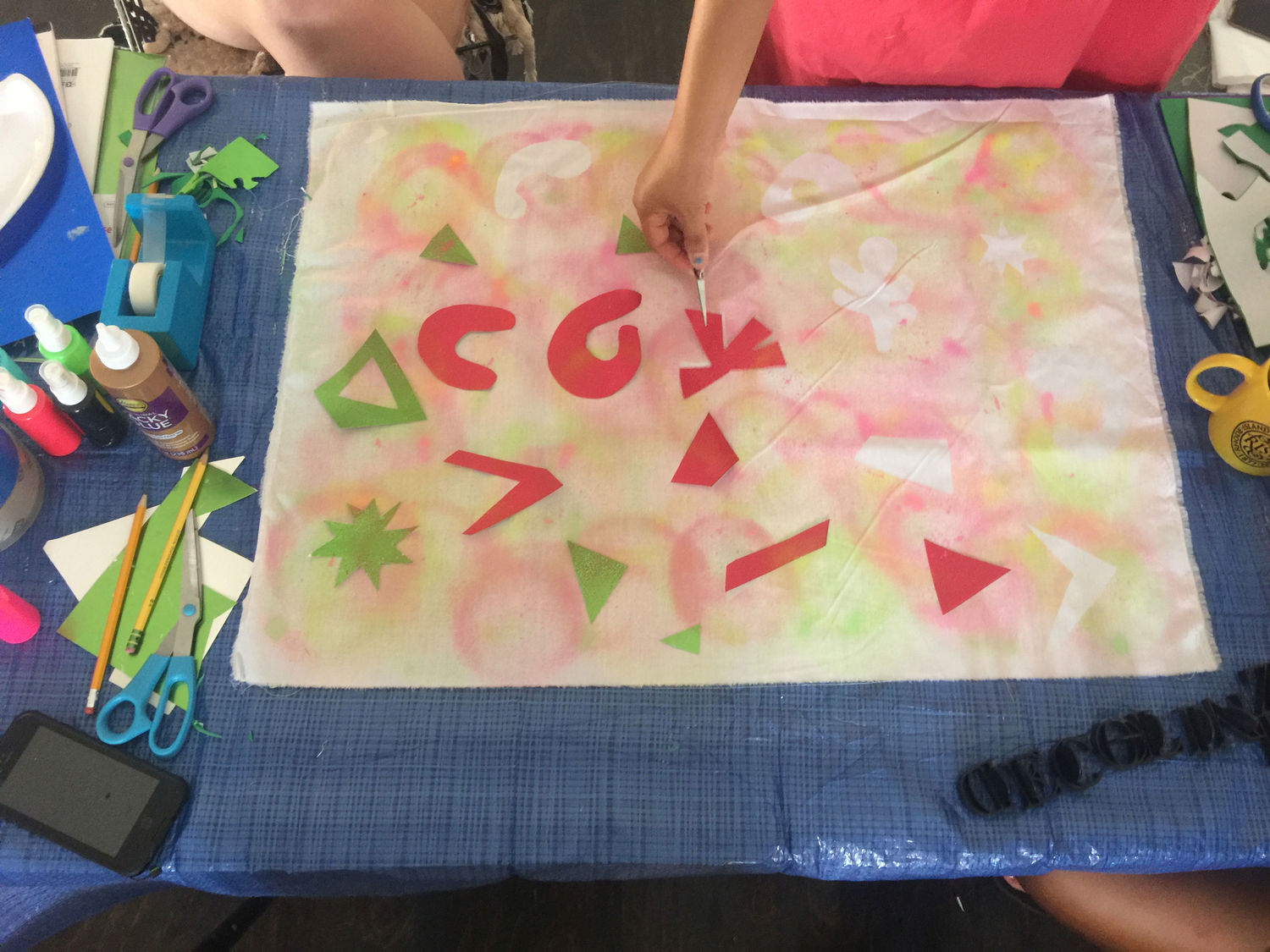

Tanya Aguiñiga, one of this year’s workshop artists, welcomed us to her studio for an interview and demonstration of her Family Day project. Aguiñiga’s workshop will invite families to make what she calls "manifesto tea towels," a dynamic blend of community empowerment and textile design. The tea towels will become part of a collective artwork that will be donated to the nonprofit organization Heart of Los Angeles.

Isoke Cullins: Can you tell us about your artistic practice and what themes you address in your work?

Tanya Aguiñiga: I use craft as a medium to diversify people’s thoughts about what art is. I mainly do fiber-based work, but my formal background is in furniture design. I’m trained as a woodworker and a metalworker. I also have a really extensive background in working with communities and using art as a vehicle for community empowerment. Recently I’ve figured out ways of working with the public that involve teaching skills, creating community, and inspiring a larger sense of empowerment through the use of everyday objects and materials.

IC: Where did you grow up? Where are you currently based? And how do those things inform the work that you make?

TA: I grew up in Tijuana in Mexico. I crossed the border every day to go to school in the United States. I grew up bi-nationally, essentially, spending days in the United States and nights in Mexico. I did that every day for 14 years until I turned 18, and then moved to the United States.

I’m currently based in L.A. I’ve been here for 12 years. I love being two hours away from Mexico, but removed enough that I can really focus on making work that expands on my idea of my own identity and my relationship to the border. Growing up on the border and crossing it every single day had a massive influence on who I am as a person and the type of work that I make. If it’s not directly related to bi-nationalism and border issues, then a lot of the work that I make is about forming community and figuring out ways to work within a non-hierarchical system. And a lot of that is from having experience with extreme power issues growing up on the border and seeing how two cultures are really pitted against each other because of socioeconomics, ethnicity, and brownness.

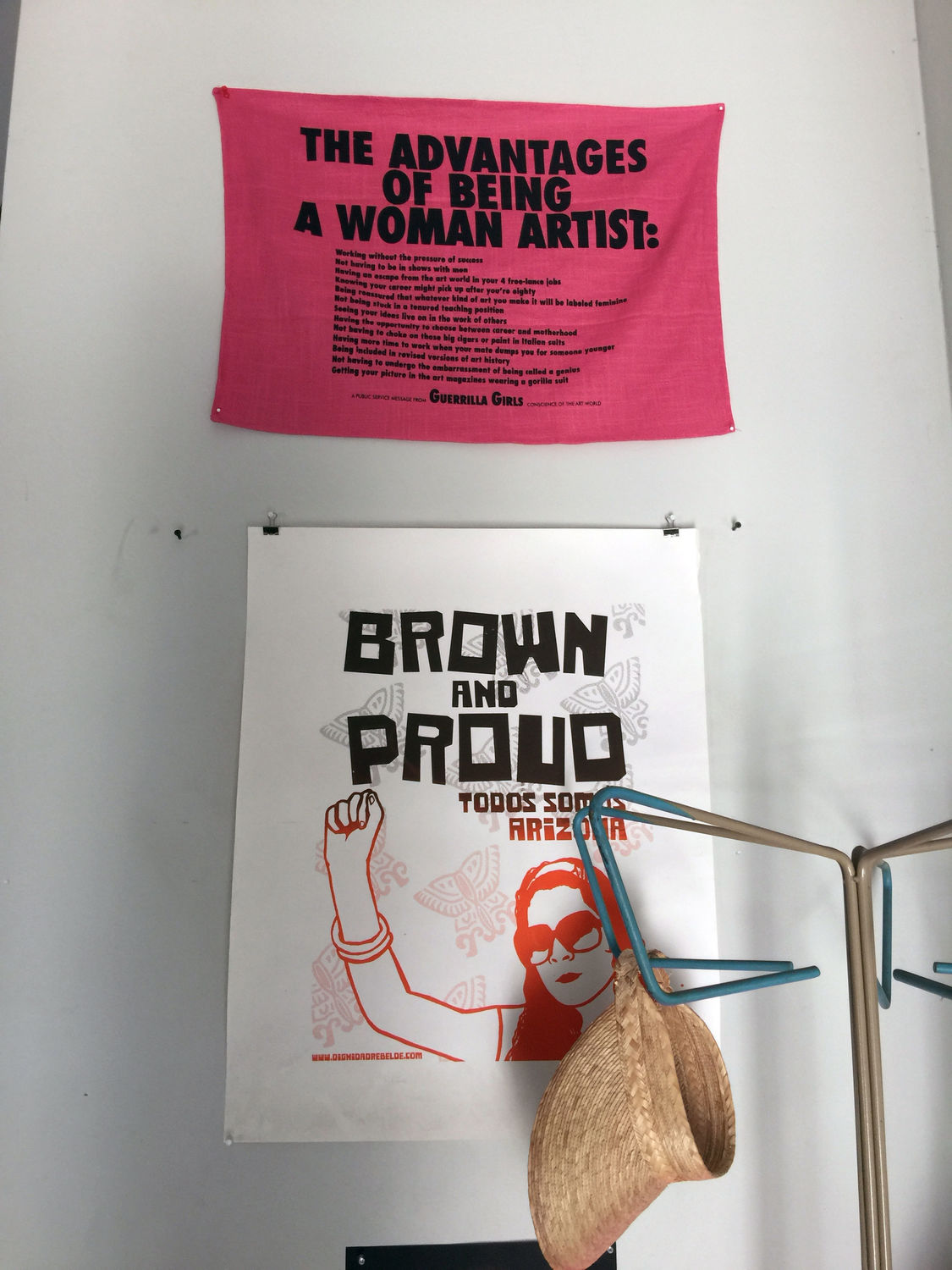

So within the studio and within the work that I do, everything is set up so that anybody can learn how to do it really quickly—anybody can add or deconstruct parts of the work that we do without there being any large change in the pieces. It’s a way that all of us can work collaboratively—having different skill levels, different backgrounds, different educational backgrounds—and come together to make a piece that is a reflection and product of us working as an ethnically diverse female LGBTQ+ community, using the studio as a way to empower those of us that work here, help us learn, and help us form stronger bonds with each other. Then the work that’s produced talks about diversity and talks about expanding people’s ideas of what art can be, and also, in a way, breaks down classification systems in art. Within art there exist so many intense stigmas about working with soft mediums and doing "women’s work." So a lot of it is about just making people think outside of what they see in art museums.

IC: And by "soft mediums," do you mean fiber-based mediums?

TA: Yes, soft mediums are often classified into the domestic sphere as "women’s work" and labeled as craft in a bad way—where it becomes kitschy. People think of the 1960s and 1970s and things that "ladies" or "grandmas" do. So we use the medium and the techniques that stem out of fiber traditions as a way of subverting what people classify as fine art and sculpture.

IC: Art, craft, and design often aren’t synonymous with each other. So what are the distinctions for you, and what would you consider your work?

TA: The way that I work is really influenced by my experience growing up on the border and having to constantly shift my own identity. So with labels, I often feel that they’re more about the person that’s trying to classify and understand me than it is about me, because it’s them projecting their sentiments about me and perhaps a lack of understanding of me and how I grew up and the region that I come from. But to me it doesn’t really matter. For the most part, I let people classify me as whatever they need me to be for the sake of my work and what I need to do to keep my career going and get more opportunities to make a living from this work that I do. In the end, you can’t be that picky about what you’re being called if you have no money. Even having a choice of making fine art work is something that I don’t have the option of doing, because I don’t have financial backing. The studio employs a lot of amazing women, and I am responsible for their wellbeing. So it’s one of those things, like, whatever people want to label me as is fine, as long as you let me in the door.

That’s the hard thing with a lot of the materials that I work with. They are really “working class” materials. Sometimes people have a really hard time letting them be anything other than "decorative arts" because they think it’s pretty, it’s soft, and I can pet it. How do you expand the notion of what art is and reiterate that craft is a massive part of art making and the conversation in art?

IC: When did you decide that you wanted to be an artist, and how did you come into this specific practice?

TA: I decided that I wanted to study art in community college. The main reason that I went into functional art—furniture design—was because I was always really artistic but I felt guilty studying fine art because I come from a really working class background. The only way that I felt that my work could still be relatable to my own family was if they could appreciate the craftsmanship and the "handwork" in something. It’s different when you can sit on something or have it be useful versus just look at something.

Furniture design skills also translate pretty directly to jobs. If I can’t make a living as an artist or furniture designer, I can totally be a carpenter or a contractor. There’s something justifiable about having useful everyday skills. People of color don’t have that many real and tangible examples of somebody being a fine artist, being super successful and having a house. It took a really long time for me to get away from making functional work and to allow myself to make art that was based in meaning and not in function. So until there are more of us out there that younger generations can mirror themselves after, it won’t be an option for a lot of people. Especially when you have to go into a lot of debt in the process, it’s hard to justify otherwise. It can seem like shooting yourself in the foot.

IC: What piqued your interest in participating in the Hammer Museum’s Family Day? How did you develop the idea for the workshop you will be leading?

TA: I became interested when I found out this year the focus for the day is community-based work and the philanthropic side of art-making. As a mother, I often think of how I’m raising my daughter, and about the ways I speak to her about other children and our responsibility to society. I think we need to teach our children to be accountable and involved citizens when they’re young, and not just when they come of voting age. One of the things that I really gravitated to was that this program is free and open to the public, and not just open to those who can afford to pay for art classes and workshops. I like the challenge of figuring out how I can use art as a way to empower young children to speak their minds. And not just speak their minds about things that are stylistic or aesthetic, but more so how I can get them to think about taking control of their own lives to suit a more diverse global experience. Children are rarely given power, so I wanted to do something that gave them the power to amplify their voices or needs.

Family Day: Art for Good is on Saturday, August 19 from 11 a.m.–3 p.m. The event is free and open to the public.