Episode 7: Connecting the Dots: Karl With to Alfred Flechtheim to Berlin

In July 2017, the Hammer will launch its digital archive Loss and Restitution: The Story of the Grunwald Family Collection, exploring the life of Fred Grunwald, a businessman and collector whose donation of prints to UCLA created the foundation of what is now the UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts. In this 7-part blog series, project researchers Kirk Nickel and Maia Woolner will share how they recreated Grunwald's story through archival research, from his early collecting days in Germany to the seizure of his collection by the Gestapo to his emigration to the United States and rebuilding his collection.

Among Fred Grunwald’s many acquaintances in the Los Angeles arts community during the 1950s was the art historian Karl With. In 1933, the Nazis had forced With out of his position as director of the applied arts museum in Cologne, and by 1950 he had begun teaching at UCLA. The Getty Research Institute holds With’s personal papers, including the manuscript of his autobiography and his copious notes, so our team made the short drive up Sepulveda hoping to find the art historian commenting on his relationship with Grunwald and maybe even on his fellow German émigre’s print collection.

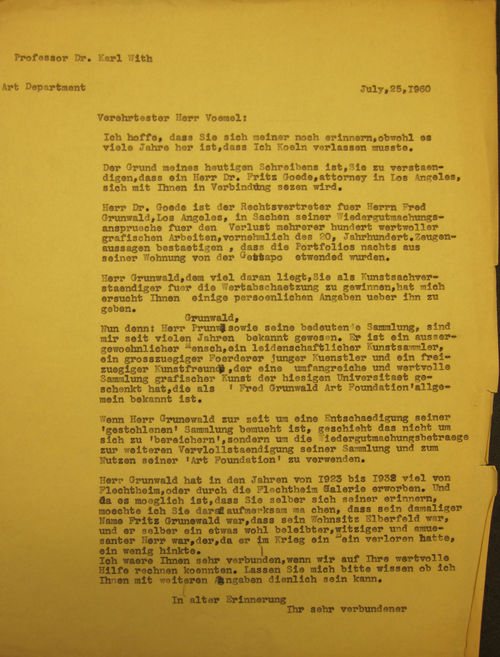

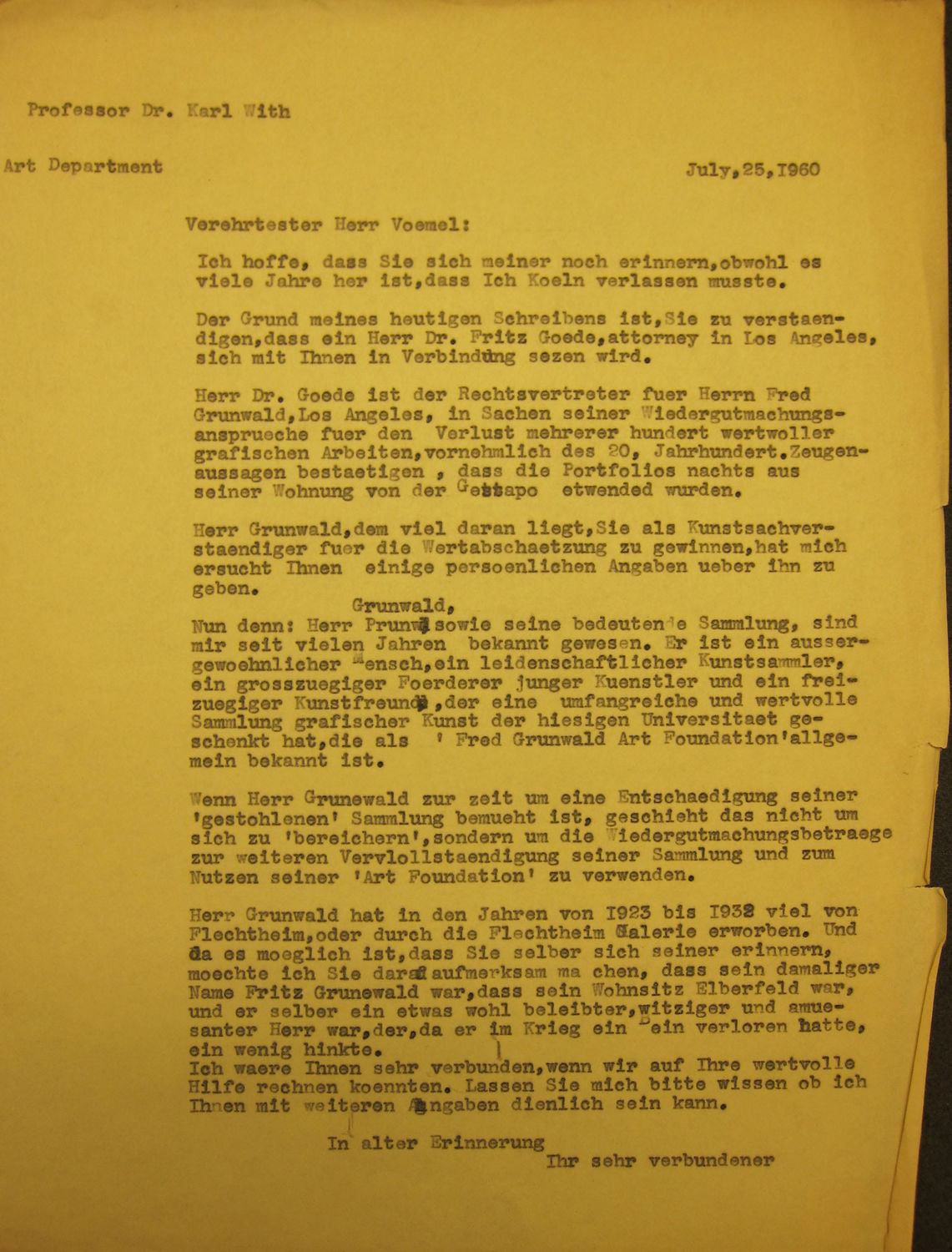

What we found was a copy of a letter from With to the art gallerist Alex Vömel written on Grunwald’s behalf. In July 1960, With contacted Vömel in an effort to secure the gallerist’s support for Grunwald’s effort to receive restitution for the prints that the Wuppertal Gestapo confiscated from him in the mid-1930s. As With’s letter relates, Grunwald had purchased many of those lost prints from Galerie Flechtheim in Düsseldorf, where Vömel had worked.

The discovery of this letter proved to be an enormous breakthrough for our research. It revealed that Grunwald was buying prints from Alfred Flechtheim, Germany’s most important dealer of modern art, and, by bringing Flechtheim into consideration, it also presented us with a parallel and well-studied example of Nazi-era art confiscation and post-war restitution. Knowing the current location of the restitution claims filed by Flechtheim’s estate (information published on the exemplary website www.alfredflechtheim.com), we could continue our search for Grunwald’s claims paperwork with far more precision.

And things began happening quickly. We soon located the claim application and settlement documents related to Grunwald’s lost print collection in Berlin in the archives of the Federal Office for Central Services and Unresolved Property Claims (Bundesamt für zentrale Dienste und offene Vermögensfragen). Grunwald had not received his lost prints; they were, and remain, unidentified. Rather, the value of these records for our research project lay in the claim’s accompanying documentation. Affidavits attached to the claim included the testimonies of witnesses verifying the existence of Grunwald’s pre-war collection and recounting its confiscation by local Gestapo agents. And Grunwald also provided affidavits testifying, at times quite specifically, to the prints he remembered having owned. Not quite an itemized inventory but still a gold strike.