Episode 6: The Claims Conference

In July 2017, the Hammer will launch its digital archive Loss and Restitution: The Story of the Grunwald Family Collection, exploring the life of Fred Grunwald, a businessman and collector whose donation of prints to UCLA created the foundation of what is now the UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts. In this 7-part blog series, project researchers Kirk Nickel and Maia Woolner will share how they recreated Grunwald's story through archival research, from his early collecting days in Germany to the seizure of his collection by the Gestapo to his emigration to the United States and rebuilding his collection.

In 1952 the Claims Conference was organized in New York City by representatives of Jewish organizations from across the world. Their goal was to help advocate for Jewish victims of Nazi persecution by fighting for indemnification. The primary compensation program for individuals was set up in the 1950s by a number of German federal compensation laws known as the Bundesentschädigungsgesetz.

When our research team began searching for documentation housed in German archives, it wasn’t obvious where we should start. Kirk eventually made a great find following the trail of one of Fred’s pre-WWII dealers, Alfred Flechtheim. The route I took was to reach out to the Claims Conference, which is still in operation today. The administration informed me that the central registrar would help me locate where in Germany any specific claims files according to the BEG laws would be housed.

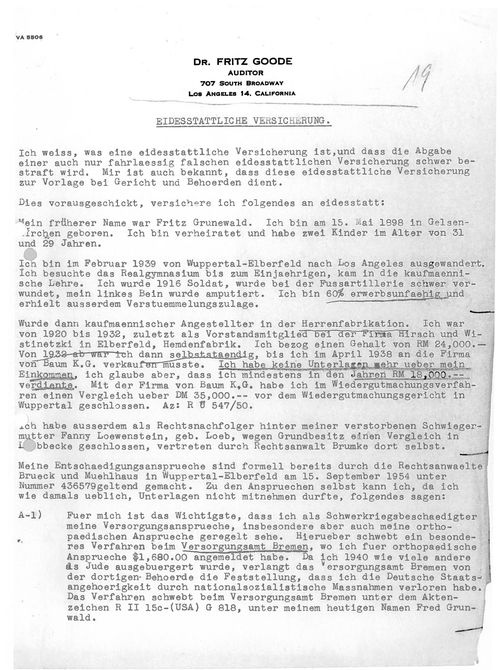

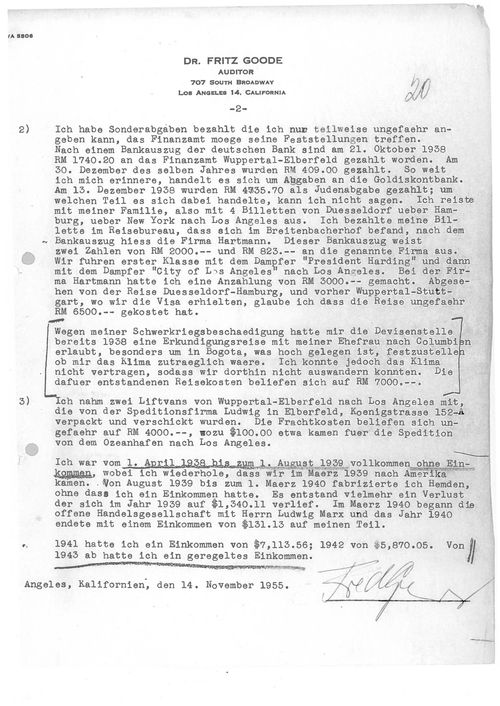

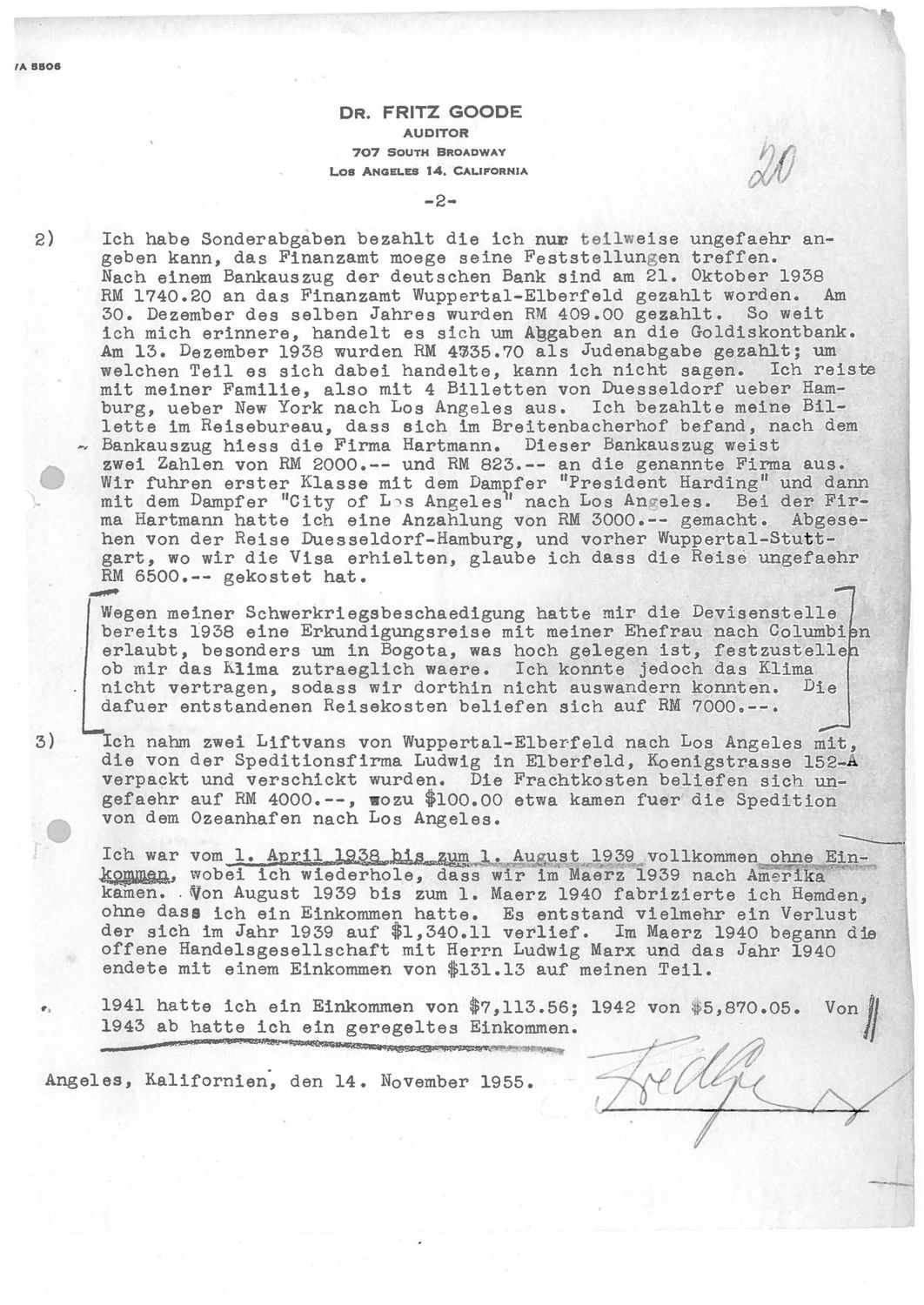

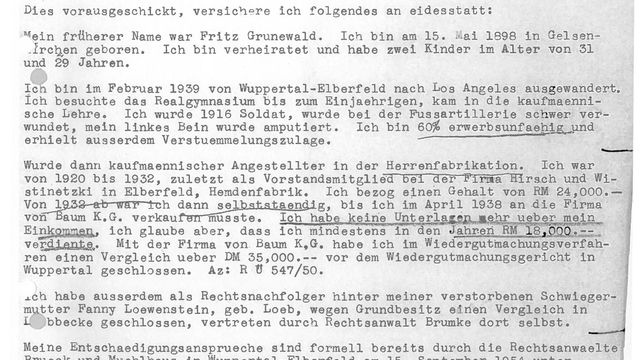

Further claims documents pertaining to restitution Fred sought after the war were held in archives in Dusseldorf. When we received these, it became clear that Fred not only filed claims for his confiscated art, but also for the loss of his manufacturing business, his pension and income, and also for medical and relocation expenses incurred when he and his family fled Germany.

It took quite a lot of back and forth with the archive to actually have them send us the files we wanted. But there was a lot of excitement when the package finally arrived in the mail and we’re grateful that making a trip to Germany wasn’t necessary. And one has to admit: there’s something really satisfying about finding the documents you’ve been looking for. While it’s important that historians don’t fetishize the archive, locating lost documents is undoubtedly one of the greatest pleasures of doing historical research.