Vallotton: The Woodcuts of Modern Life

Each fall, the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts selects a small group of UCLA undergraduate art history majors to participate in a special independent study exploring the history of printmaking in the western world. Drawing primarily on the center’s remarkable collection of over 40,000 objects, this unique opportunity offers students hands-on experience handling, examining, and cataloging works on paper while also learning more about the cultural context in which these objects were produced. Taught jointly by Cynthia Burlingham and Leslie Cozzi, the Grunwald Center’s director and curatorial associate, the 2016 course focuses on innovations in 19th century printmaking and related arts. Complementing their other course work, this student-authored blog series presents reflections on some of the most significant artists and artworks of the period while providing our visitors unique insight into treasures of the Grunwald Center collection.

For more information on the Grunwald Center Research Internship and how to apply, please visit the “In Partnership” section of the UCLA Art History department website.

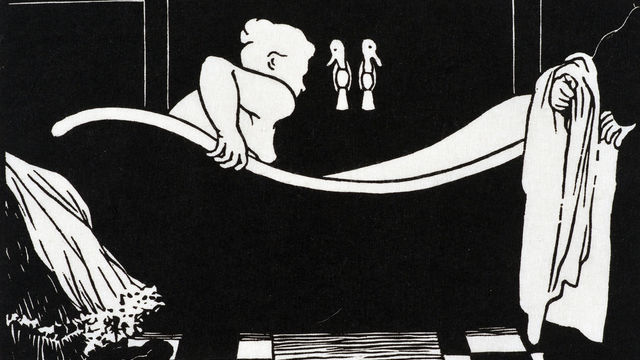

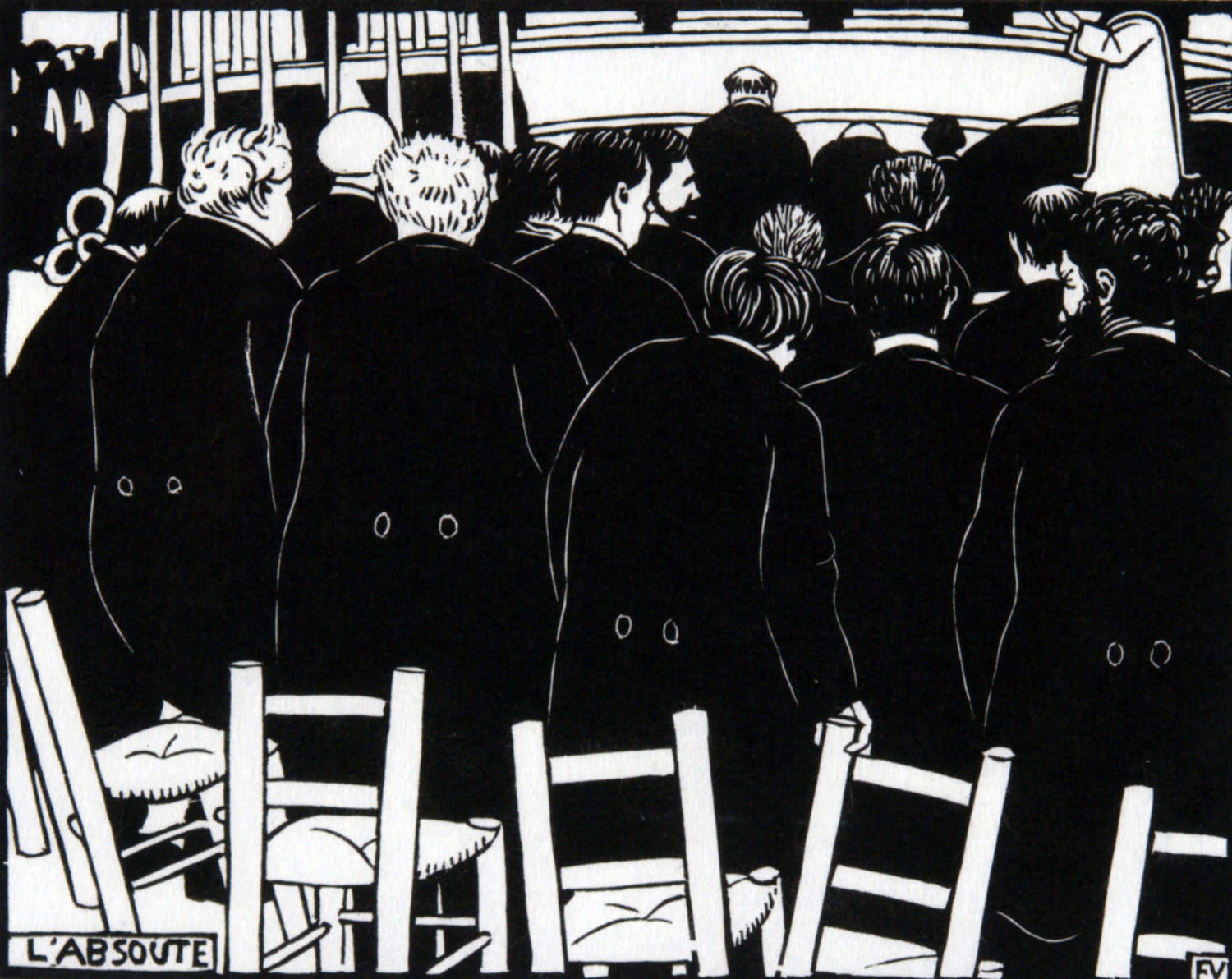

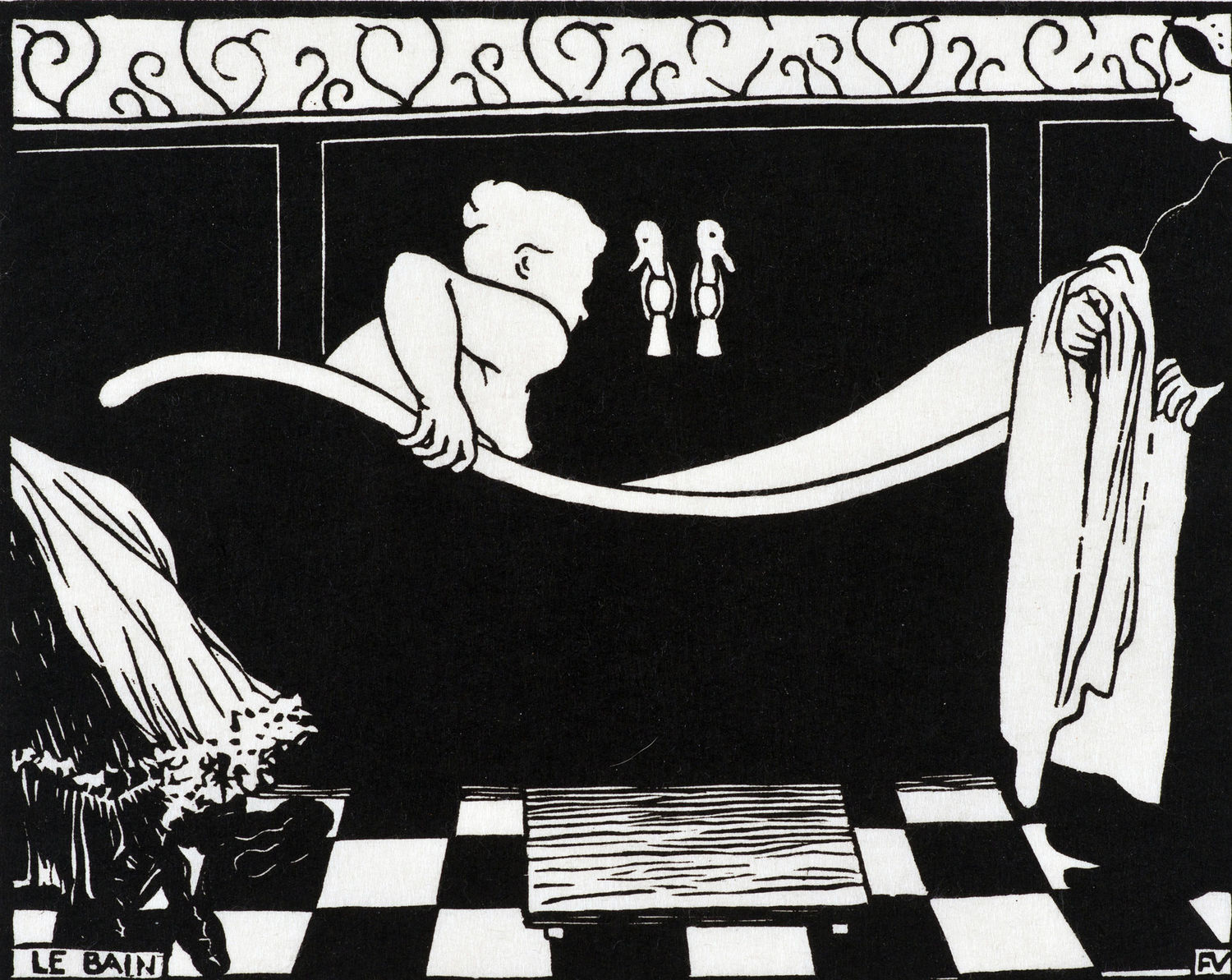

Félix Vallotton was associated with the group of French artists known as the Nabis, a word meaning 'prophets' in Hebrew, whose short-term affair with color lithography shifted to a renewed interest in woodblock printing thanks to the influence of Japanese prints in the late 19th century. This foreign aesthetic influence, spawning a style of European Japonism, spread to France and became increasingly admired among both artists and the masses. While young artist-printmakers such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec focused on vibrant color lithography, which was still a relatively new technology, Vallotton looked toward a more traditional form of reproduction in the form of woodblock printing. Unlike the multicolored and ukiyo-e Japanese prints, Vallotton chose to work exclusively in flat, unmodulated black and white, which simplified forms and relied on strong linework and high-contrast lighting to create scenes of Parisian life. Woodblock printing allowed Vallotton to evoke the aesthetic linear qualities of ukiyo-e while including the popular post-Impressionist subject of life in the city during rapid growth and change due to industrialization.

Each print focuses on an aspect of modern life in Paris during the World's Fair, including busy transit on a bridge, a cluster of bourgeois adults and children in the streets, a crowded entrance to an Orientalist performance, and a cluster of faces in awe of launching and exploding fireworks. These works could be viewed as uneventful in subject if one were to compare them to some of Vallotton's prints which critique police brutality or offer insight into the dynamics of changing relationships between men and women, but they can be considered nuanced in their realistic snapshots of what someone could not escape in the city: the crowd. The modern city offers a great deal of recreation options, with the city street corner itself being a unique, free source of entertainment and intrigue in the form of people-watching, sightseeing and urban exploration. Those who took advantage of this activity, the bourgeois flâneurs, a term meaning "strollers," had the luxury of leisurely exploring the city landscape would become a symbol of modernity. Charles Baudelaire optimistically characterizes the flâneur as a curious intellectual, a "passionate spectator... feel[ing] oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world" (Baudelaire 9). Vallotton seems to present his crowds in a less-than-positive manner, not highlighting their freedom to wander but instead calling attention to the sheer number of people present who make it difficult to navigate such a busy space. According to Walter Benjamin in his critique of Baudelaire, the industrialization of cities and clear class divisions allowed the flâneur to safely navigate the city thanks to exterior passageways called arcades, which shielded them from the real dangers of the outside, while still providing a means for urban exploration (Benjamin 36). With the bourgeois masses engaging in city life, there is increased demand for recreation and the need to enjoy the spoils of modernism. Their activity was eventually fraught with alienation and frustration, as the city became impossible to navigate due to the influx of citizens and tourists walking the streets thanks to the commercialization of public spaces partly due to events such as the World's Fair.

Vallotton's stark, black and white prints are a call to the past, present, and future of printmaking and the graphic arts, although the publication of prints by Vallotton's contemporaries sharply declined by 1900. As Carey and Griffiths point out, "Bonnard and Vuillard abandoned the medium, while Toulouse-Lautrec was a dying man... the transformation, even if overstressed here, is remarkable and makes the question of why the movement collapsed almost as puzzling as the question of why it suddenly arose in the 1890s" (18). After 1900, the act of flâneurie had also mostly subsided, as crowds and industry took over public spaces. Félix Vallotton had also shifted into oil painting and became successful in playwriting as well as art criticism. However, his woodcut prints will remain as a window into a subcultures, influences, and changes in modern France.

Works Cited

Baudelaire, Charles. The Painter of Modern Life, in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, edited and translated by Jonathan Mayne. London: Phaidon Press.

Benjamin, Walter. Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism, Harry Zohn, trans. London, 1983.

Carey and Griffiths. From Manet to Toulouse-Lautrec: French Lithographs 1860-1900, pp. 11-20.