Hermann-Paul’s Modistes

Each fall, the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts selects a small group of UCLA undergraduate art history majors to participate in a special independent study exploring the history of printmaking in the western world. Drawing primarily on the center’s remarkable collection of over 40,000 objects, this unique opportunity offers students hands-on experience handling, examining, and cataloging works on paper while also learning more about the cultural context in which these objects were produced. Taught jointly by Cynthia Burlingham and Leslie Cozzi, the Grunwald Center’s director and curatorial associate, the 2016 course focuses on innovations in 19th century printmaking and related arts. Complementing their other course work, this student-authored blog series presents reflections on some of the most significant artists and artworks of the period while providing our visitors unique insight into treasures of the Grunwald Center collection.

For more information on the Grunwald Center Research Internship and how to apply, please visit the “In Partnership” section of the UCLA Art History department website.

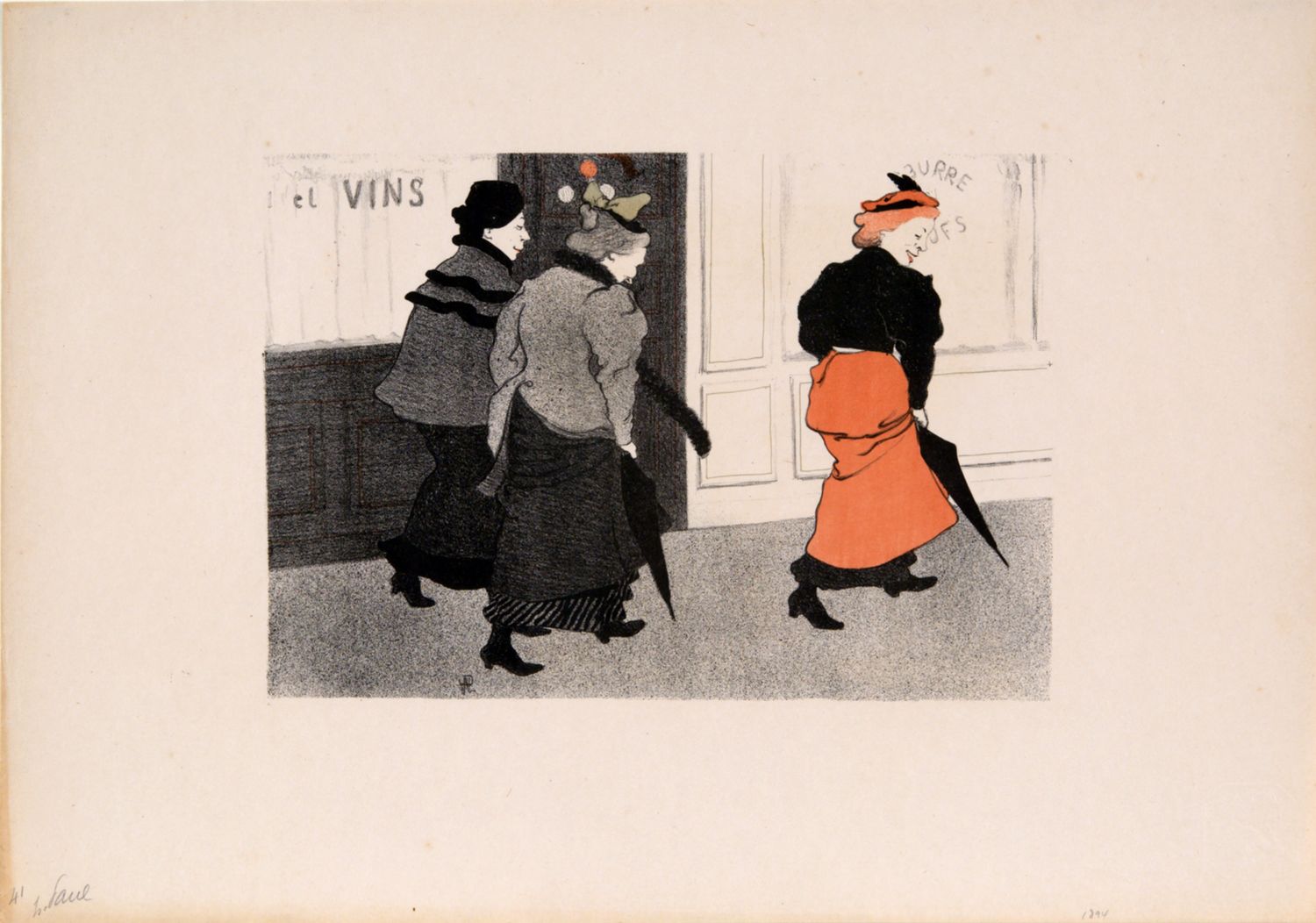

At first glance, René Hermann-Paul’s 1894 lithograph, Modistes, appears to depict three modistes—or hat makers—walking down the street. There doesn’t seem to be a narrative, instead it is a fleeting moment captured by Hermann-Paul. Color is not used throughout the whole piece, and the limited palette of red and green highlights specific aspects of the piece. While the unusual, sporadic use of color may draw in the eye, the overall image doesn’t seem to be much more than an everyday stroll down a Parisian street, complete with shop windows displaying goods like wine, butter and eggs. A closer look, however, reveals that there is more to these women than first meets the eye, especially the woman in front.

Doused in a red wash of color, the leader glances back with her lips parted and pulls up her skirt to reveal her ankles. The color itself is suggestive. Red is often seen as color of passion or lust, so for her to be largely composed of it hints at her nature. This interpretation of color also synthesizes with her gesture and facial expression. Today, this is not particularly scandalous, but in the late 19th century this gesture would have been understood as provocative. As she looks back, it is unclear if she is looking at her companions or the viewer of the piece, but her parted red lips can also be read as a suggestive signal. They imply that this woman may not be more than just a hat-seller. In fact, modistes in were associated with prostitution. The prostitute was a well known subject for artists during this period and in this piece Hermann-Paul seems to be playing with the idea of what it means to be a working woman.

The use of color also speaks to the ways that artists at this time were interested in other cultures. Japanese prints were becoming increasingly popular and the Nabis—the artistic group that Hermann-Paul was a part of—took an interest in appropriating Japanese techniques and styles to incorporate in their work. As explained by Frances Carey and Anthony Griffiths in their book—which, in this passage, also cites André Mellerio, an 18th and 19th century art critic—“The oriental influence was largely responsible for the Nabis’ avoiding les mélanges excessifs aboutissant aux fadeur prétentieuses du chromo [excessive mixtures leading to insipidity of color] in favor of broad, flat areas of unmodulated color: un jeu large de colorations sincères où l’oeil puisse s’étaler nettement [a broad set of sincere colors wherein the eye can spread significantly],” (Carey and Griffiths, 18). This is clearly seen in Modistes, as all the colors are done in broad zones. The wash helps to pull the focus to specific areas of the piece and flattens the space where it is used. It is also interesting to note that Hermann-Paul used foreign techniques to create an image that seems so distinctly Parisian.

By combining the Japanese techniques with common themes and gestures, Hermann-Paul is able to create a complex piece. While at first it does not appear to be more than an everyday stroll down the street, the modistes, especially the women in front, could be interpreted in other ways. Everything about her—her gestures, facial expression, color of her dress—implies that, like the produce behind her, she is also for sale. Hermann-Paul plays with what it means to be a working woman in period with an increased emphasis on consumerism.

Bibliography

Carey, Frances, and Antony Griffiths. From Manet to Toulouse-Lautrec: French Lithographs, 1860-1900: Catalogue of an Exhibition at the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, 1978. London: British Museum Publications, 1978. Print.