Telescope: China | Li Zhenwei

In 2008, Hammer Projects curator James Elaine relocated to China. He has since settled in Beijing and opened the nonprofit art space Telescope. Jamie is our feet on the ground and bring us his musings on art, life in China, and anything else that might strike his fancy.

Even as a young child trained in traditional eastern and western painting, Li Zhenwei was always peering over the prescribed ways of making art into other worlds and ways of expressing himself. At the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing, in one of his first classes he was given several potatoes and told to go home and to draw them for a month. Li went home, but instead of drawing the potatoes, he cooked and ate them. This didn’t endear him to his school and its traditional demands but spoke of his desire to seek a different way: his way.

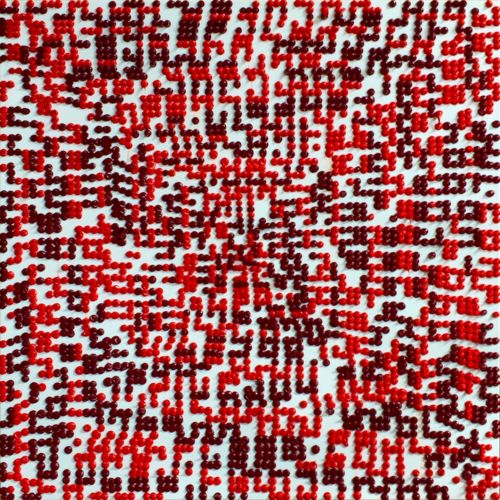

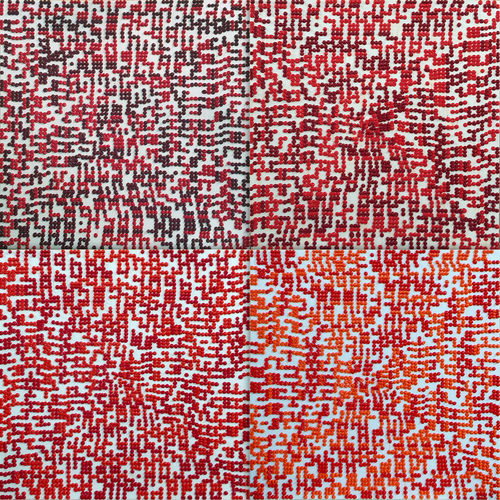

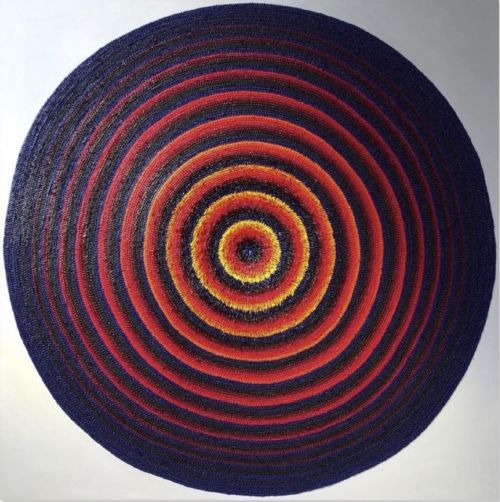

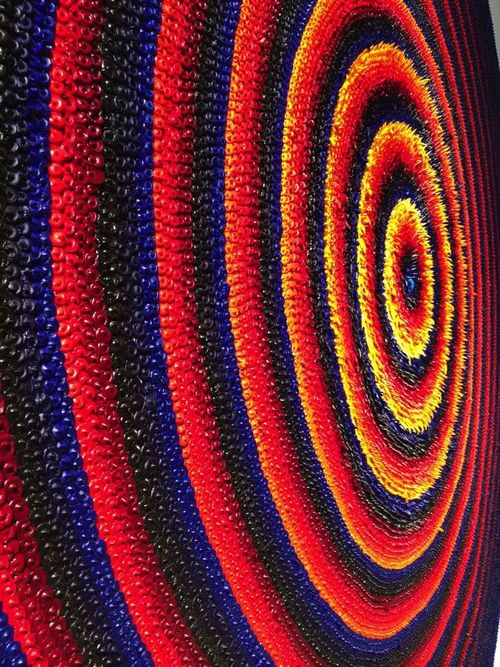

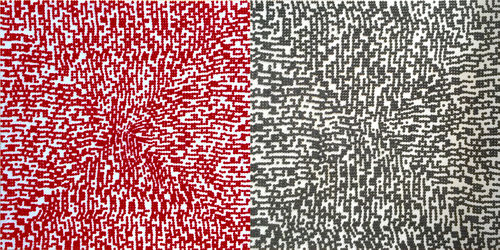

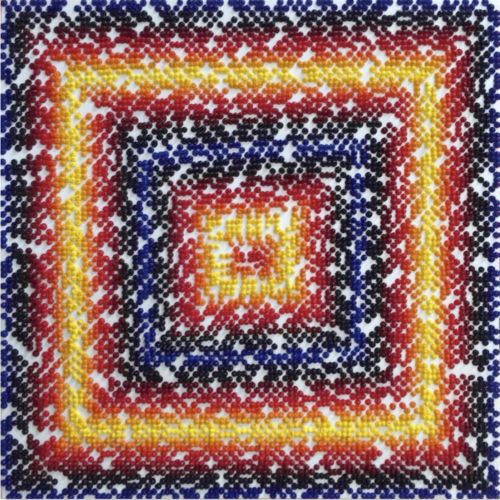

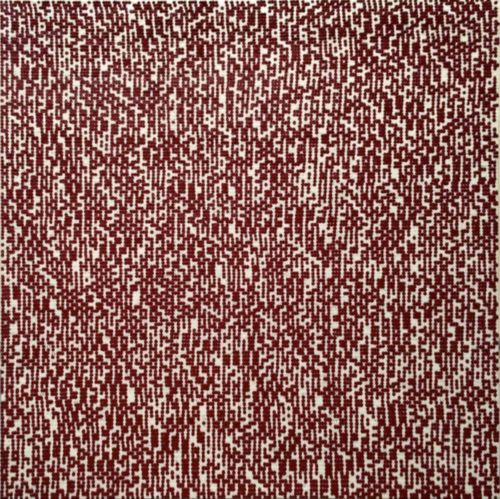

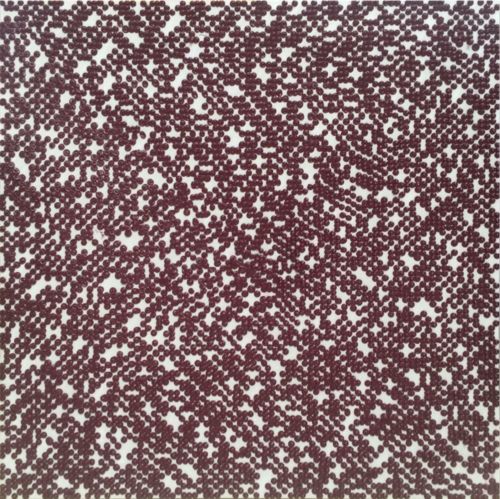

During his second year at the art academy, a teacher who took a liking to Li, gave him a studio in a remote area outside of Shenyang in northeast China. He gave him some paints, told him to have a good time, and then left him there alone. Li now had paint, a studio, solitude, but no brushes. As Li sat alone on the roof of the building he thought, “why do I need to use a brush to apply paint to canvas?” “Why do I need to take paint out of a tube, put it on a intermediary surface, then transfer it to canvas with a brush or another tool? “It is too indirect.” As a child studying art, Li was first taught how to draw a ‘perfect’ circle, and from the circle he was shown how to draw a tiger and all other things in nature. Li states, “Everything can be reduced to a circle, a dot.” In the ancient world it was believed that the sky was a circle and the earth was a square within it. “Their understanding of the natural world was limited and wrong at times but their lives were more simple and honest than ours are today,” Li says. We have greater scientific knowledge and understanding but we have not advanced as a race along with it and our problems have not been solved but are growing even worse. “We are no stronger today than we were centuries ago.” Even if the earlier concepts Li employs are incorrect, Li wants to simplify his language in art to the purest elemental form he can: a dot (a drop of paint). Using PI—a real but transcendental and irrational number with a non repeating decimal point that is never the same and has no end—as his system for making his work, and oil paint applied directly from the tube to the canvas, he inverts the ancient knowledge and traditional painting techniques, by conceptually painting the circle in the square. “You can’t have a circle without PI,” Li notes. At a first glance, Li’s paintings might look simply repetitive, and they are to the degree of PI, but they are not identical, either. Their simplicity belies their almost mystical depth. There is a spiritual presence in the paintings, and like spirit, one cannot really tell how it operates or where it comes from. Li’s paintings are transcendent, solid, and always changing, which time reveals.

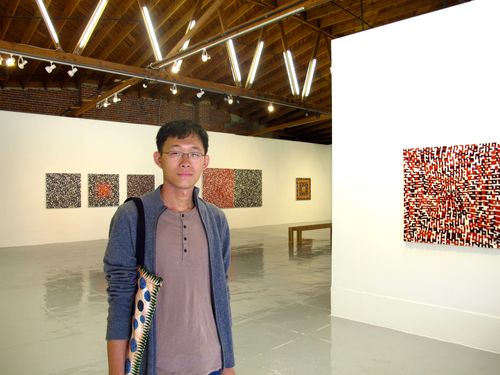

Li Zhenwei's Predictable Irrational is on view at MAMA Gallery, Los Angeles from September 10–October 23, 2016.

Li Zhenwei’s work is also included in Under Heaven: Contemporary Art from China in the Ahmanson Collection, Ahmanson Gallery, Fieldstead, Inc., Irvine, CA. from August 19–November 31, 2016.