Silence and Anger in Daumier’s Rue Transnonain

Each fall, the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts selects a small group of UCLA undergraduate art history majors to participate in a special independent study exploring the history of printmaking in the western world. Drawing primarily on the center’s remarkable collection of over 40,000 objects, this unique opportunity offers students hands-on experience handling, examining, and cataloging works on paper while also learning more about the cultural context in which these objects were produced. Taught jointly by Cynthia Burlingham and Leslie Cozzi, the Grunwald Center’s director and curatorial associate, the 2016 course focuses on innovations in 19th century printmaking and related arts. Complementing their other course work, this student-authored blog series presents reflections on some of the most significant artists and artworks of the period while providing our visitors unique insight into treasures of the Grunwald Center collection.

For more information on the Grunwald Center Research Internship and how to apply, please visit the “In Partnership” section of the UCLA Art History department website.

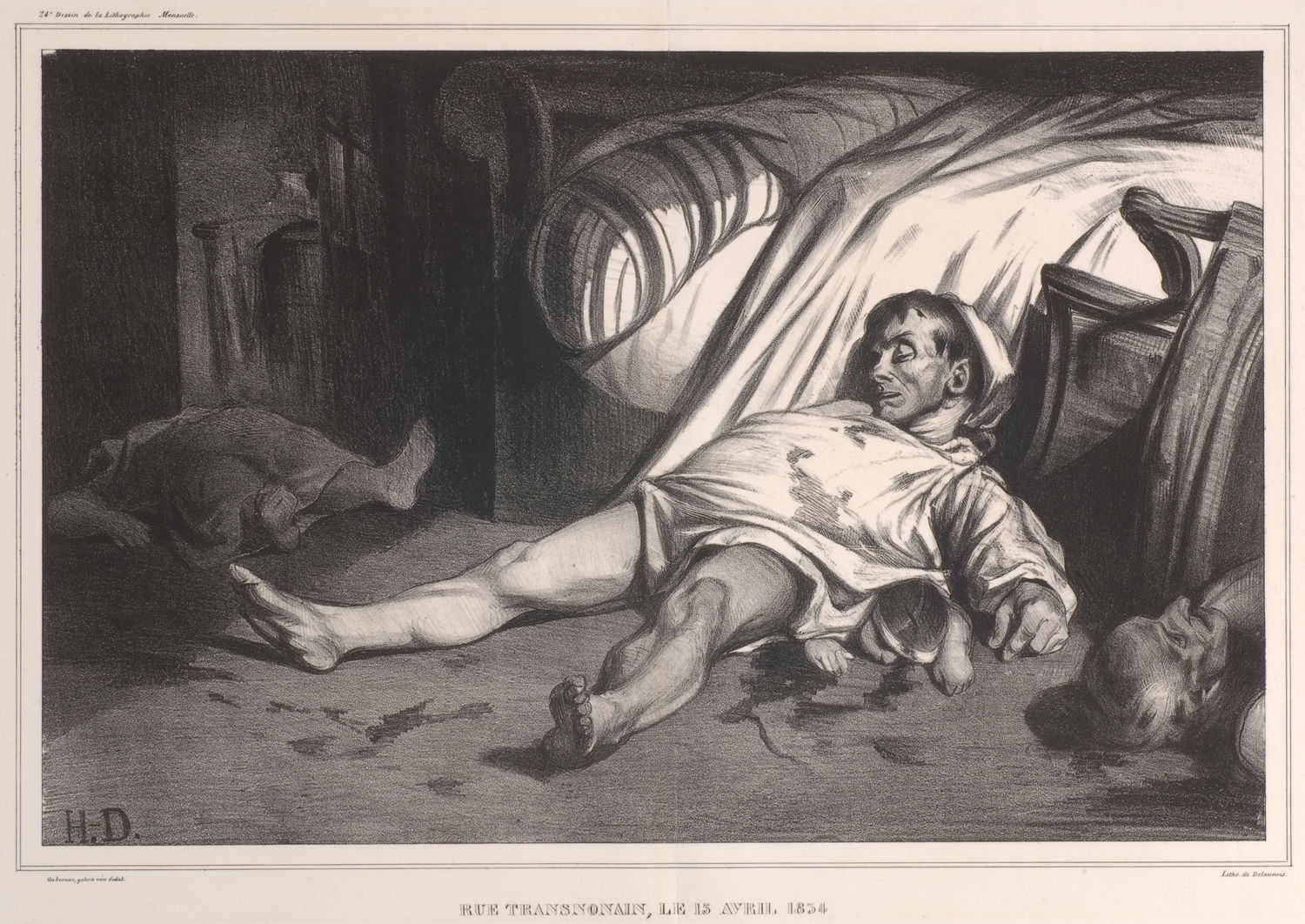

Honoré Daumier was a prominent French printmaker during the 19th century. Known for his prolific body of work—over 4,000 lithographs—Daumier shaped French satire with his acerbic wit and keen observations. Drawing from current events, his caricatures and satirical images—depicting everyone from King Louis Philippe to a cuckolded husband—critique the social and political life of France at the time. His work often exaggerates traits of his subjects to play upon certain aspects of their character, like depicting King Louis Philippe as an engorged giant devouring his subject’s wealth. One of his greatest works, however, does not follow this pattern. Rue Transnonain, created in 1834 in response to political unrest, presents a dramatic imagining of a massacre of innocents. While the piece draws from current events, there is an unnerving sense of silence and anger not found in his other works.

Charles Philipon, editor of three of the satirical journals Daumier contributed to, remarked, “Daumier as a lithographer had the power of a history painter,”[1] and Le Men goes on to consider Rue Transnonain as a “history painting.”[2] History paintings most often depict moments from classical history or mythology. This print, however, is actually based on actual events that occurred in April 1834. The French government had harshly suppressed an uprising by republican supporters. French troops were later fired upon by people barricaded in a working class building on Rue Transnonain. In response, the troops entered the building and began to eradicate its occupants. Daumier reimagined the aftermath of the incident to create Rue Transnonain. The print features several victims caught in the crossfire of the massacre. Dressed only in a night shirt, the central figure is slumped over and surrounded by overturned furniture. A streak of dramatic lighting casts a spotlight on him – as if he is the haunting grand finale of a tragic play. Underneath him is the body of a bludgeoned child. While the subject matter is graphic, what is most striking about the piece is its silence. Daumier doesn’t depict the action of the massacre, but rather, the eerie quiet of the aftermath. This silence is also reflected in the viewer’s response to the work. The usual chuckles or snorts heard when people view Daumier’s satire are replaced by a somber hush. There is a certain anger not present in his other pieces. Instead of asking his audience to acknowledge the ridiculous through his exaggerated caricatures, Daumier instead forces them to face this atrocity and its consequences prompting quiet, simmering anger. In a way, this is a further testament to his artistry, as the piece seems to speak to his ability to project a range of emotions across his different works and, as Philipon claimed, elevate depictions of current events to the status of history.

While Rue Transnonain is not the typical Daumier caricature, it reveals Daumier’s emotional range. Instead of the humor that permeates most of his work, the rage in this piece effectively conveys senseless tragedy and outrage. This rawness and emotion elevates Daumier’s work far above simple cartoons.