Learning from our Paper Conservator

Have you ever heard of a paper conservator? Generally, a paper conservator restores, maintains, or prepares objects in museum collections for storage, research, or exhibition. To be frank, I hadn’t known about this career until I started interning here at the Hammer Museum. Before my internship, when I thought of museum professions, I thought of artists and curators at most. Now, I am learning that an art institution is run by many more people. The other day I had the privilege to visit Ms. Mo McGee—our very own paper conservator—at her workspace, and I would like to share what I’ve learned about the art of paper conservation.

Who is Mo?

Name: Mo McGee

Major: B.A. in Fine Arts from Clark University; M.A. in Art History from UCLA

Working as a paper conservator since: 1993

Working at Hammer since: 1996

Hobbies: Watching Barcelona soccer/football

Project 1: Discoloration

One of the two projects Mo introduced me to was the process of bathing to remove discoloration and spots. Yes, I panicked as well when Mo first mentioned that she was going to bathe artworks in water.

Jane: Is it safe to bathe?

Mo: Before you do any bathing, you have to test the media to be sure there isn’t anything that’s going to run or move in the bathing. You test and test and you re-test because you can’t be sure how things are going to behave entirely. It’s a bit of a guessing game.

Even though it seemed radical when Mo started spraying these prints with water, to my surprise, the prints did not bleed. Rather, after an hour or so, I saw that the water turned a little yellow, confirming that these prints had in fact been discolored over the years. There were also bits and pieces of tape and hinges floating around the water, marking this bathing project a successful one.

After Mo bathed the prints, she hung them on a screen for them to dry. While those two prints were being dried, Mo introduced me to another project.

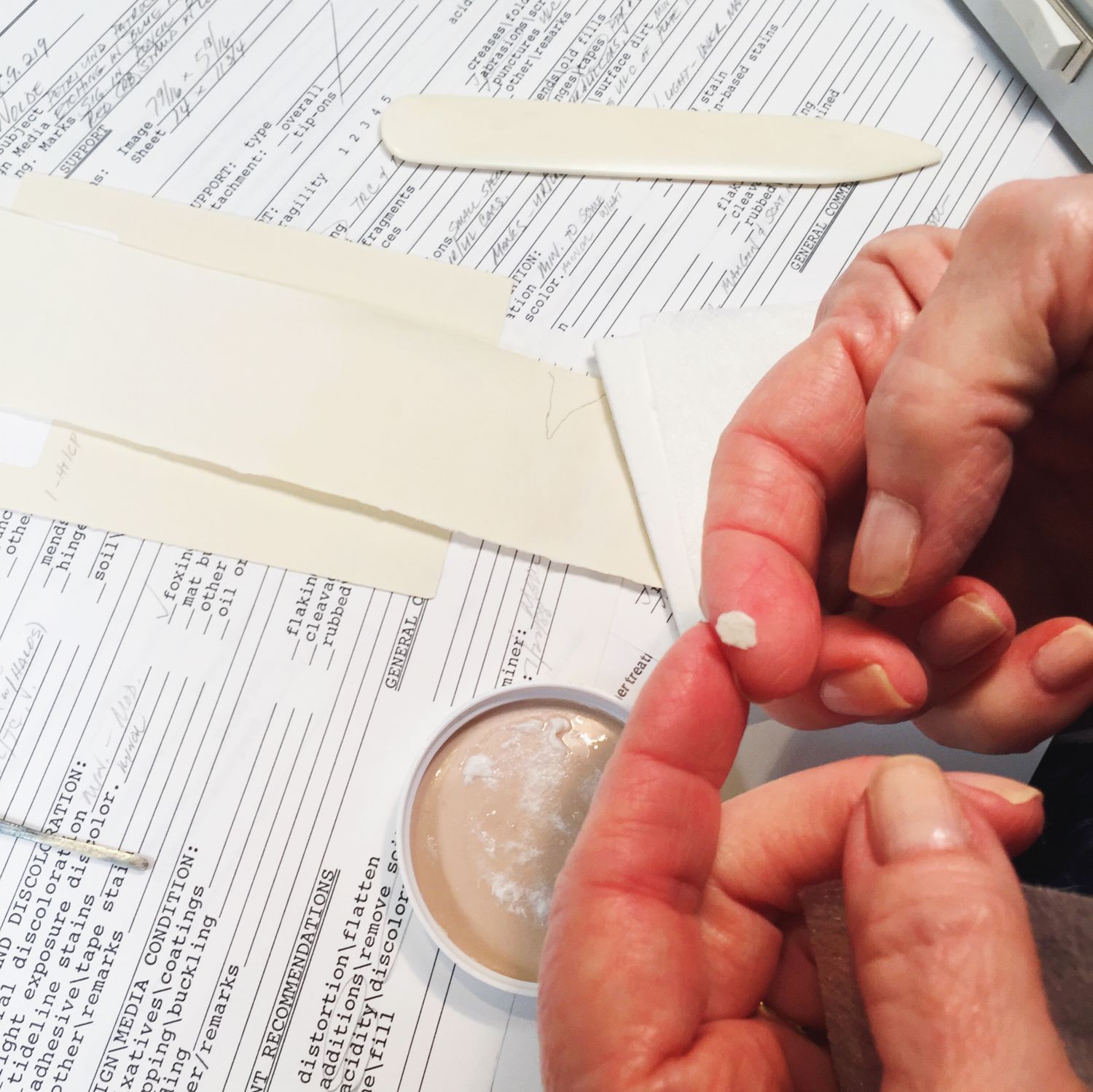

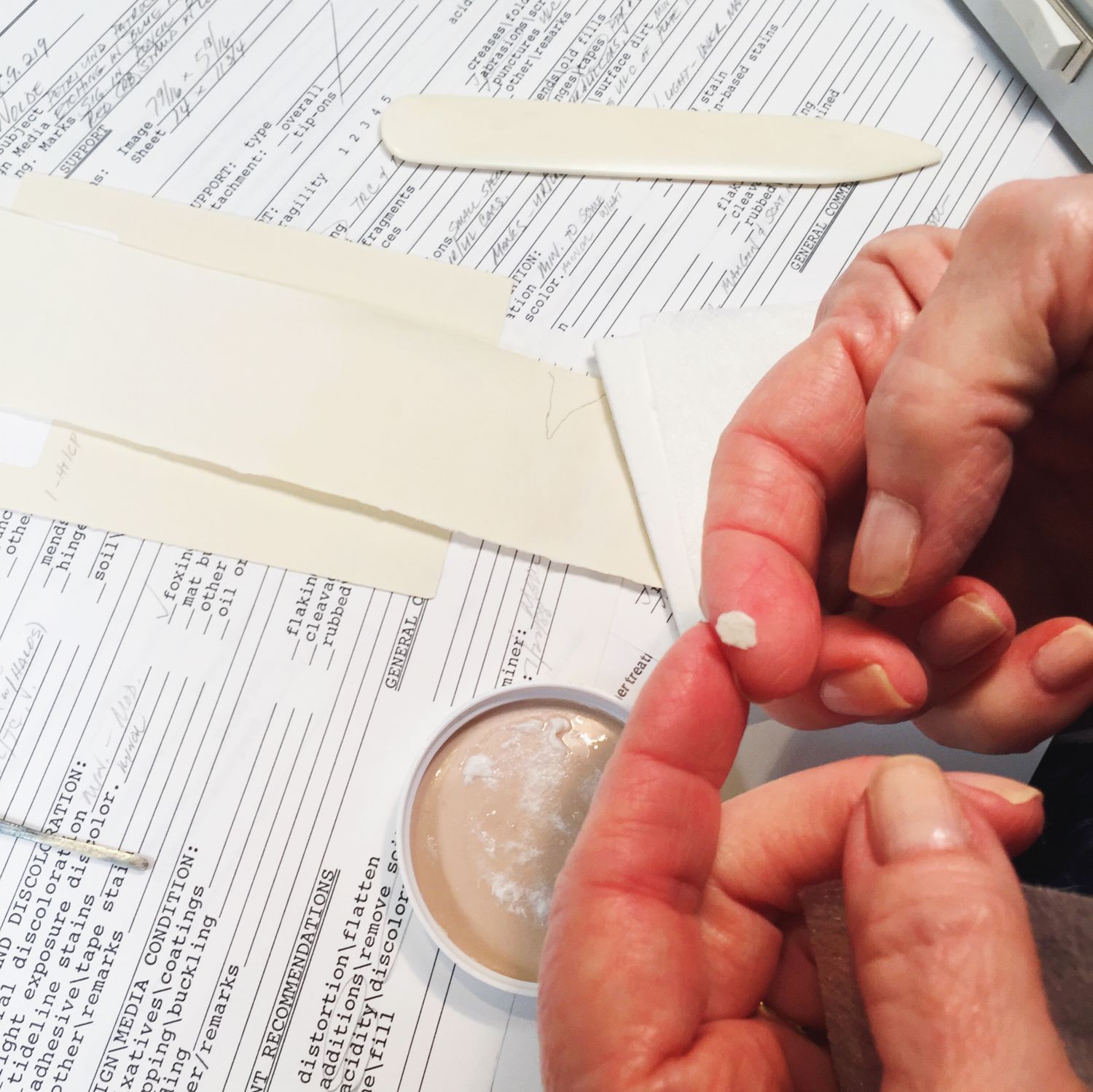

Project 2: Finding the right fiber

The second project was how to handle works with a tear. Pieces that have tears are sometimes problematic because they limit the choices of frames or borders that curators have when planning an exhibition. This is when Mo tries to find the paper that is the most similar to the original piece that will “blend into the sheet.” The process of finding or sometimes creating the replacement paper is interesting.

There are several ways of finding the perfect paper. The first method is to just look for papers with the most similar weight, color, and texture. Another method is to paint over the paper with watercolor if the color is slightly off. The most fascinating method, in my opinion, is when Mo makes her own paper with fiber that she has collected in her mini refrigerator.

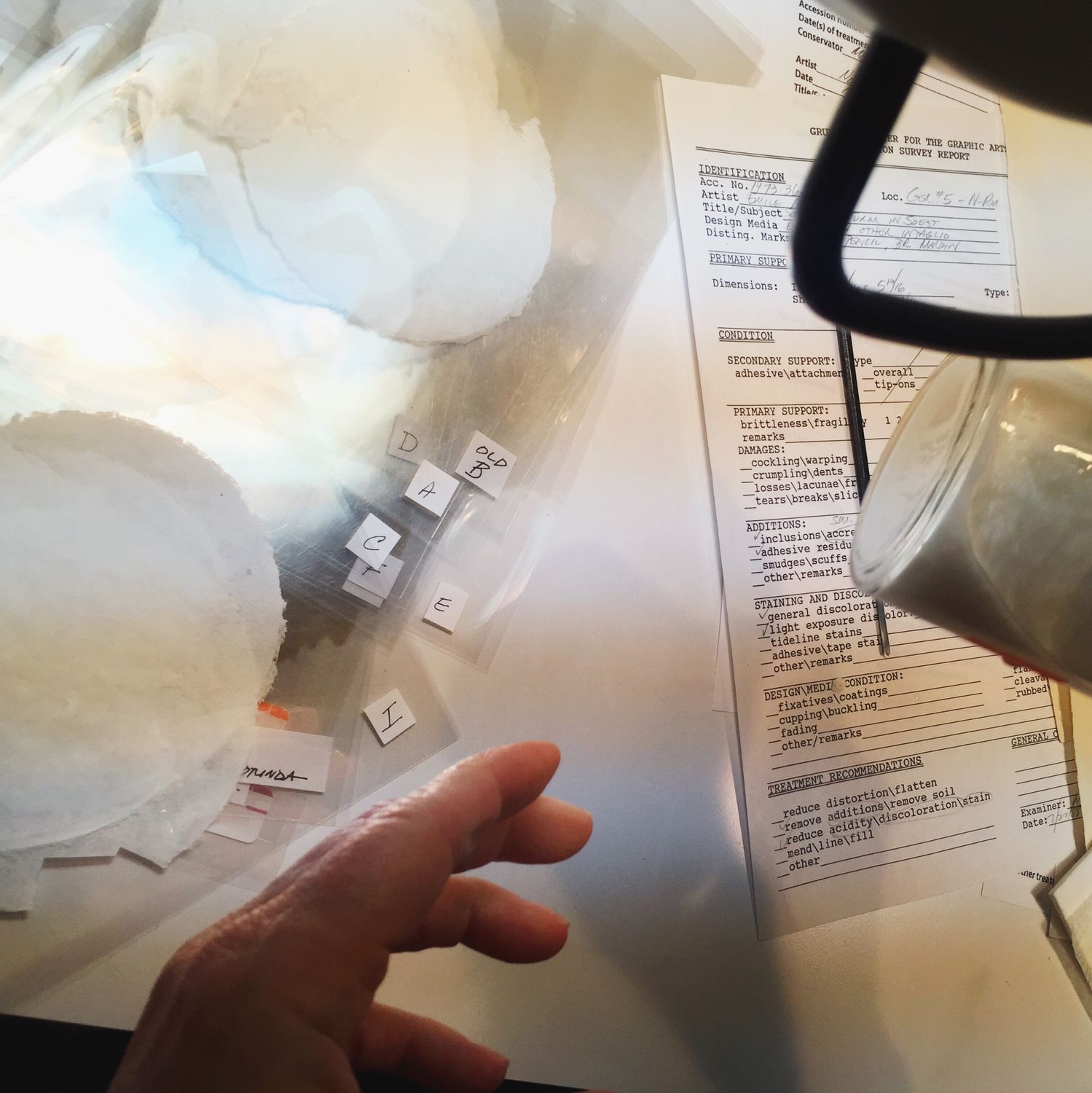

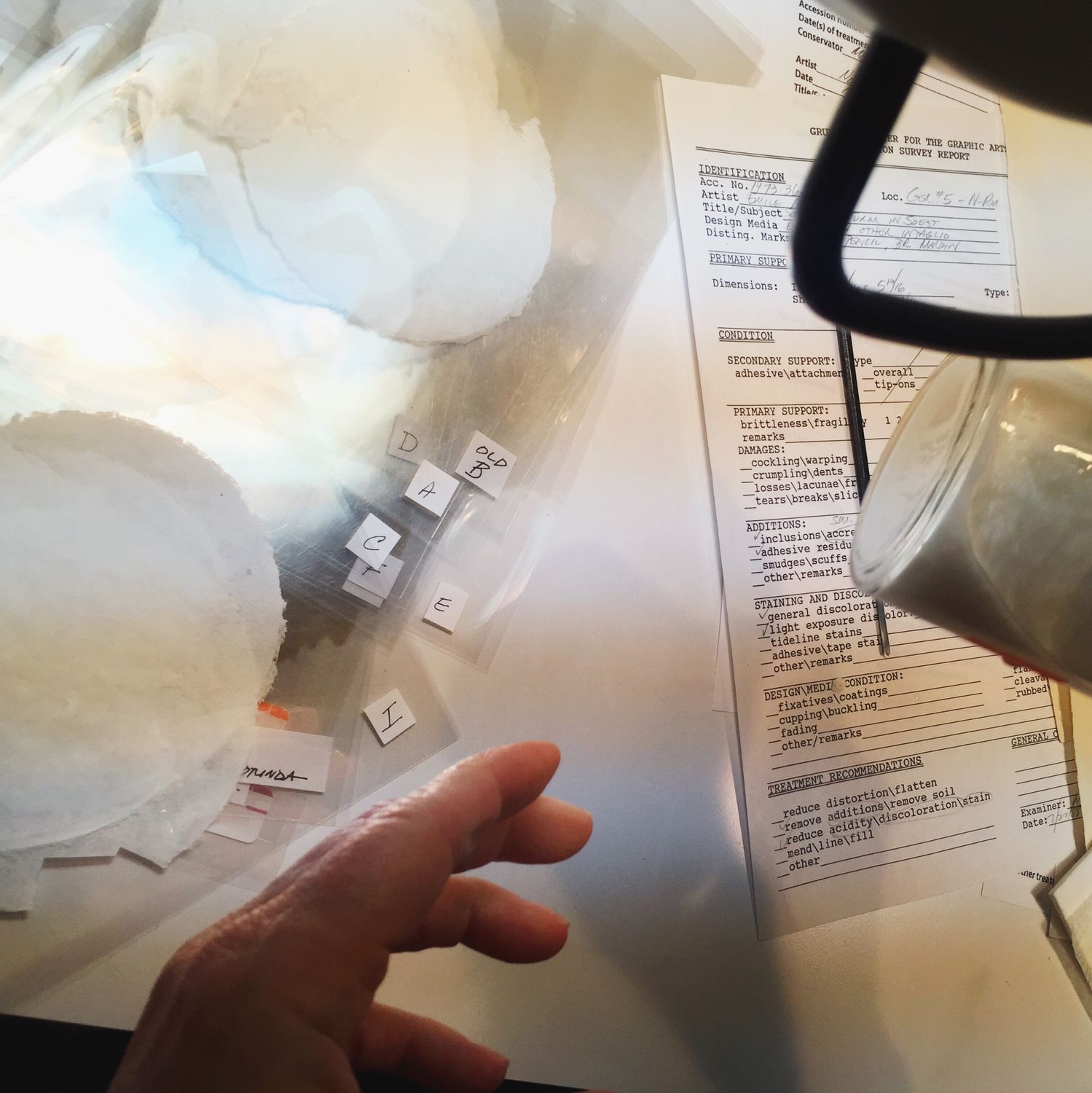

Mo showed me samples of the papers she’s made, labeled as A, B, C, etc. She not only had white fibers but also fibers of different colors that she had mixed to create various shades of whites and browns.

Conservation as Performance

After I witnessed Mo’s mastery of paper, I have come to regard paper conservation as an artistry. However, my realization is not novel, as there are people that regard conservation as a form of art.

A recent article in The New York Times was titled “Showtime at the Musée d’Orsay: Watching Varnish Dry.”

“They gather in silence to gawk at the paint whisperers — small teams of conservators poised on scaffolding and encased in two glass cubes. From these makeshift stages, they swipe away centuries-old dark grime on precious works — from Gustave Courbet’s enormous oil painting of his crowded studio to Auguste-Barthélemy Glaize’s violent battle of a stone-throwing female revolt against Roman invaders, “The Women of Gaul.”

During my visit, I asked Mo how she felt about conservation becoming a type of performance art in these museum spaces.

Mo: “I have thoughts about that. It puts the conservator under a terrible terrible pressure. People expect to see action all the time. Having an audience is not fun—feeling like you’re under a microscope all the time. It also gives the public a distorted idea of what the field is. They are only seeing a part of it and not seeing all the steps before that point and what happens after.”

Do you have what it takes?

At last, I asked Mo what three characteristics one should have to become a paper conservator, and she answered:

Patience.

Flexibility.

Curiosity. ”Each piece is unusual, and every piece has a history of its own. After it leaves the hands of the artist, it goes to whoever—buyers and sellers—and if it’s been in an institution before, it might have had modest treatment. You need to figure out as much as you can.”