Art in Conversation: Ruth Asawa and Merce Cunningham

On Sunday March 6, my fellow student educator Audrey and I facilitated an Art in Conversation with museumgoers in Leap Before you Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957. Just half an hour long, Art in Conversation is designed to place two artworks in conversation with each other. While we choose to focus on works from Leap Before You Look, the tour can just as often place a work from the Armand Hammer Collection in dialogue with a piece of contemporary art. Regardless of the pieces chosen, our aim as facilitators is to draw out the resonances or dissonances between artworks. We hope our guided conversation allows visitors to approach the museum’s exhibitions and artworks attentive to how they might place pieces throughout the museum in direct conversation.

Leap Before you Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957 is the first exhibit to offer US museumgoers a sweeping look at the diversity of artistic and pedagogical experiments that animated the college. Founded in 1933, Black Mountain College was to become an important training ground and artistic laboratory for some of the most influential artists in the postwar period. Such artists included people like John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, Ruth Asawa, Cy Twombly, Gwendolyn and Jacob Lawrence, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, and Buckminster Fuller.

Josef and Anni Albers, who immigrated from Germany prior to the outbreak of WWII and as the Nazi party was consolidating power, arrived at the college in 1933 and had a lasting impact on the school’s pedagogy. The two had met at the German art school Bauhaus when Josef was a teacher and Anni a student, and they brought that school’s sensibility to their teaching: an interest in training across artistic mediums, a focus on craft, and a rigorous investigation of materials. While there are numerous points of entry into the exhibition, Audrey and I choose our pieces guided by the Albers’ pedagogy. We wanted to highlight how teachers and students worked across artistic mediums, developing arts practices and philosophies informed by the school’s radical interdisciplinarity.

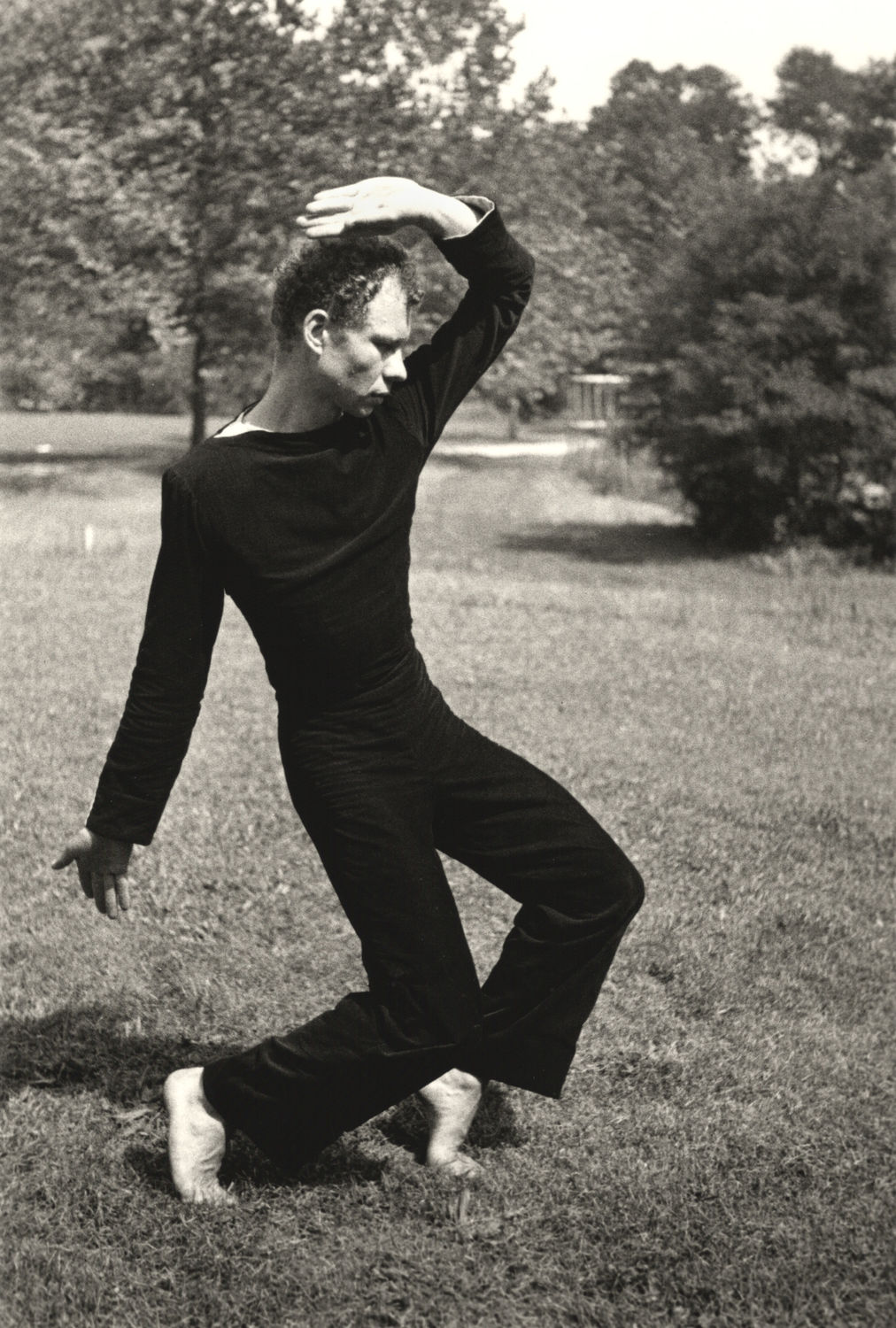

The first piece we discussed was Ruth Asawa’s woven, hanging sculpture Untitled (S. 272), ca. 1955. Asawa was a student at BMC from 1946-48. She developed the intricate method of crocheting metal wire after her time at BMC, but the spherical and organic form the sculpture takes—and which was to define a portion of her sculptural work throughout her career—emerged while she was a student at BMC. A series of early paintings completed during her time at the college depict those same amorphous spheres. One of the key influences on her sculptural practice was the experience of taking dance classes with choreographer and dancer Merce Cunningham. Intrigued by that information, Audrey and I paired Asawa’s piece with a four-minute film clip of Cunningham’s dance piece Septet from 1953. The piece, choreographed over the summer of 1953 while Cunningham was in residence at the college, includes movement vocabulary that was to become key to his distinct style: sustained poses, controlled and rigid bodies, disconnected movements, and intended dissonance between the music and movements.

Audrey and I were not sure whether tour goers would be interested in the link between these two artists or whether Cunningham’s influence on Asawa’s style would be apparent. We began asking visitors for their initial impressions of Asawa’s work. For the next fifteen minutes, the two of us said relatively little as visitors described the sense of movement they saw in the work and its organic, fluid form. One visitor drew our attention to the spheres that were nestled in the sculpture’s interior, while another noted how the shadows the work cast on the gallery floor extended its sense of movement. Transitioning to the Cunningham film, we asked visitors again to describe their initial impressions of the film clip. While more hesitant to discuss dance, the group drew out the dance’s reliance on almost sculptural-like movement, moments of stillness, and the composition of dancers across the stage. In the end, our conversation highlighted the movement and fluidity of Asawa’s static sculpture and the stasis and rigidity of Cunningham’s dance. While Audrey and I initially set up our Art in Conversation to think about Cunningham’s influence on Asawa, visitors drew our attention to how one might see a sculptural influence in Septet.