Lunchtime Art Talk Recap: David Rodes on George Bellows

I want to commemorate the 100th anniversary of World War I—the so-called “Great War,’ and “the war to end all wars,” and pose some questions about the “dark art” of propaganda and its intersections with documentation and art making.

In late October of last year, I was in London and saw at the Tower of London a magnificent, poignant installation of 888,246 ceramic poppies. “Blood-Swept Lands and Seas of Red” commemorated the number of British and Commonwealth soldiers killed in the four years of the war, though it is estimated that altogether some 38 million people and 8 million horses died or went missing or were seriously wounded before the Armistice on November 11, 1918.

Britain, who entered the war against Germany on August 4, 1914, opened that autumn its first “War Propaganda Bureau,” often just referred to as “Wellington House.” They solicited advice from such national figures as H. G. Wells and Rudyard Kipling and quickly brought out their first pamphlet documenting the real and alleged atrocities perpetrated by Germany against neutral Belgium, whom Germany had invaded preemptively in fear of an attack by France, who was allied with their enemy Russia.

The terrible plight of the Belgians—and, in particular, the death by firing squad of British Red Cross nurse Edith Cavell on October 12, 1915—became rallying cries for the British and, indeed, the Americans—against the “Huns.” (Indeed, I can remember my own Texas grandmothers being still incensed decades and another world war later.) As Prime Minister Lloyd George said, the global conflict was “horrible …and beyond human nature to bear.”

Certainly, at the heart of Allied documentation and propaganda was Cavell’s death for “treason” for helping some 200 Allied soldiers to escape from German- occupied Belgium, along with the German U-boat sinking of the Cunard Lusitania on May 7, of that same year, with 1,198 civilian passengers drowned—the ship sank in 18 minutes!

But before I talk about the murder of Nurse Cavell, let me speak briefly about the American artist George Bellows, who himself never visited Europe, but was passionately in favor of America’s entry into the Allied cause, which took place officially in April of 1917. As a frequent magazine illustrator and celebrated artist, he used his gifts to make powerful documents of German war crimes.

Bellows was born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1882, and went to Ohio State, where he played baseball and sold magazine illustrations. By 1904, without having graduated, he was in New York studying with the artist Robert Henri, founder of the gritty, avant-garde “Ashcan School” and “The Eight.” By 1906, Bellows had his own studio, and by 1909 he was teaching at the Arts Students League. In 1916 Bellows installed a lithography press in his studio; altogether, he made over 100 lithographs. He helped hang the seminal Armory Exhibition of 1913, and was by then America’s most famous artist. He died in 1925 of peritonitis at the age of 42, leaving behind a wife and daughter.

Bellows was particularly known for his vibrant boxing scenes. His “Dempsey and Firpo” painting and lithograph of 1924 are probably the most famous depictions in the entire art of sport. The fight itself, in September 1923, was titanic between “the Manassas Mauler” and the “bull of the Pampas.” Firpo was knocked down 7 times in the first round, but then he knocked Dempsey into the press box. Dempsey eventually won; and Bellow, himself an athlete, claimed, “I don’t know anything about boxing. I’m just painting two men trying to kill each other.”

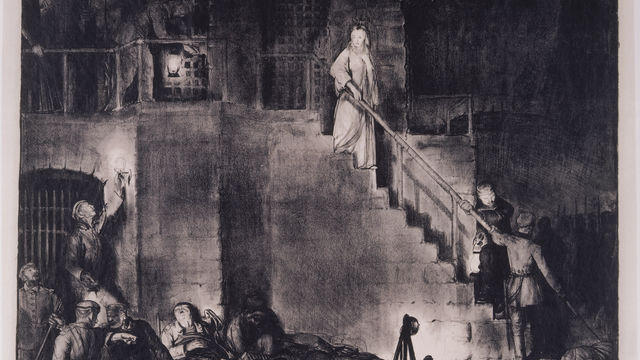

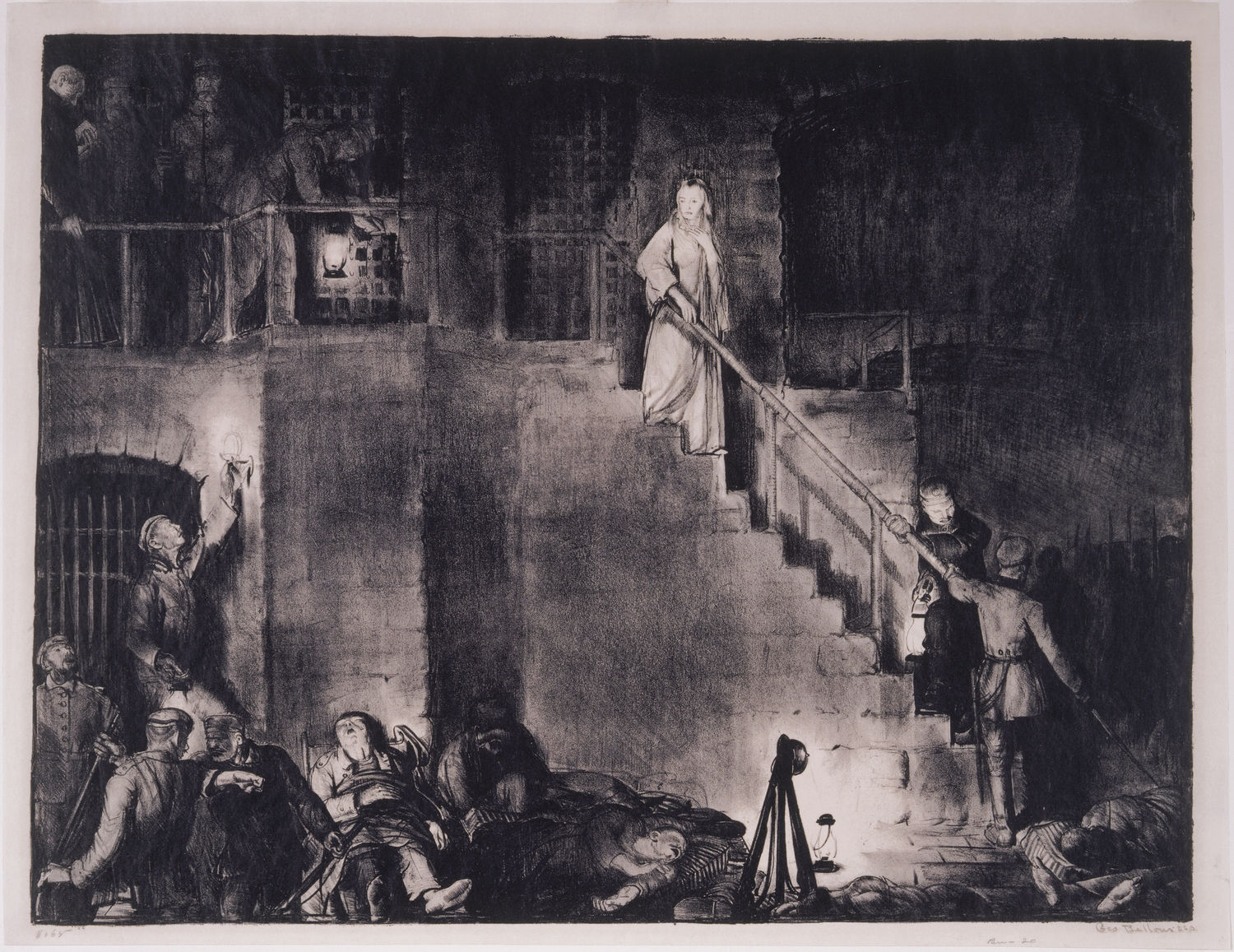

Though associated with left wing causes and something of a libertarian, Bellows was passionate that America enter the war. In just 6 weeks in early 1918—to bolster American resolve—he created 11 lithographs under the heading “War.” The specific incidents and imagery in these intense works were probably based on the James Bryce Report of 1915, which contained some 1200 depositions about German atrocities in 1914-15 Belgium: “”Murder, lust, and pillage prevailed…on an unparalleled scale,” the Bryce report concluded. In turn, from his lithographs, Bellows made 5 large-scaled paintings, including a dramatic one of the murder of Edith Cavell.

Of all of these intense “Belgium War” lithographs, the Murder of Edith Cavell is the most eerily serene, catching a moment of candle-lit calm, when she was awakened at 2 am on the morning of her execution. Contrast the violence of “The Village Massacre” and “Belgium Farmyard” with the Cavell print, which is less directly emotional and narratively direct. You had to know the story—but everyone—everyone—did!

Indeed, Cavell was the most prominent British casualty of World War I, a martyr to the horrors of war as surely as if she figured in a print by Caillot, Goya, or Manet.

The distinguished American Minister to Belgium Brad Whitlock had tried valiantly to save her, but without success. A German official replied to his pleas that his only regret was that he did not have “3 or 4 old English women to shoot.” A square in Brussels, Place Edith Cavell, commemorates her sacrifice, and a grand boulevard honors Whitlock.

When Cavell’s body was returned to England after the war, she received a full peal of Grandshire Triples at Dover—muffled, in a gesture of respect normally reserved for the body of a dead sovereign. Her state funeral was held at Westminster Abbey, and she is buried in Norwich Cathedral near the tiny Norfolk village where she grew up.

Surely, Bellows used his art to create both poignant documentation and powerful propaganda.