Lunchtime Art Talk Recap: Andy Warhol, Unidentified Woman

One of the great joys of my job is having the opportunity to pull works of art from the Hammer collection for our visitors who often would never have had the opportunity to see these pieces in person. It was certainly a treat to pull a selection of Andy Warhol’s Polaroid photographs for this Lunchtime Art Talk.

While Andy Warhol is one of the most well-known artists of the 20th century, his process and use of photography had remained largely unexamined until in 2007 the Andy Warhol Foundation launched the Andy Warhol Photographic Legacy Program to give the public greater access to his extensive archive. The foundation donated over 28,500 of Warhol’s original Polaroid photographs and gelatin silver prints to more than 180 college and university museums and galleries across the country, including the Hammer.

History of Polaroid

The instant camera dates back to 1947 though it did not go into commercial production until the 1950s. The popularity of this new technology is clear, with the first fully automatic camera, the SX-70 Land Camera, attaining a production rate of 5,000 per day within a year of its appearance in 1970.

The ubiquity of Polaroid came at an auspicious moment for photographers. Whereas in the 1960s photography remained aesthetically conservative; in the 1970s artists were able to break convention and play with the idea of mechanical reproduction itself. [1] Polaroid encouraged this interest among artists; even developing an “Artist Support System” in the 1960s with selected artists receiving free equipment in return for artworks donated to Polaroid.

Warhol's Use of Polaroid

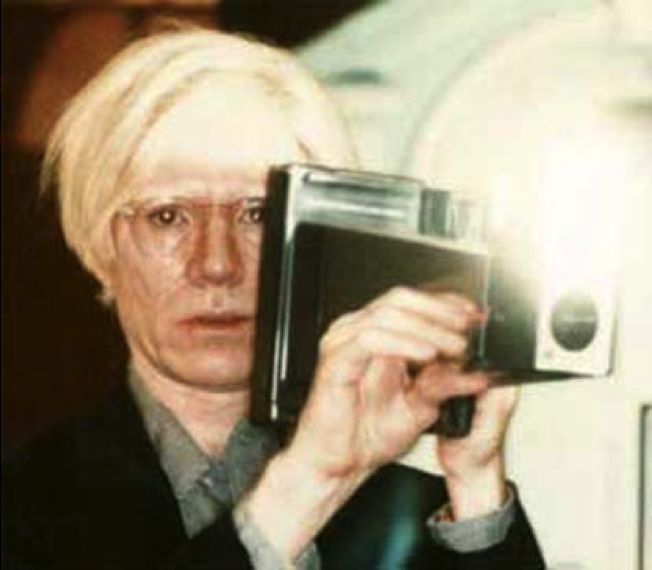

While many artists experimented with the potential of Polaroid as an artistic medium (including Robert Heinecken, whose Iconographic Art Lunches I wrote about in August), Warhol was particularly interested in the commercial use of the media, utilizing the BigShot camera, a rigid-body model produced in 1971 exclusively for portraiture. The BigShot was a clunky model with a fixed focal distance of only a few feet, a single-speed mechanized shutter, flash diffuser, and a fixed-focus rangefinder. This all means that Warhol was forced to move his own body in relation to the sitter to achieve focus, a physical and intimate act that disrupts the mechanized methodology so often associated with both Warhol’s process and with the Polaroid medium.

Many of Warhol’s Polaroid portraits depict famous faces from Blondie, to Caroline, Princess of Monaco, Muhammad Ali, or tennis legend John McEnroe in a family portrait with Tatum O’Neil and their newborn baby. Beyond celebrity, he often photographed wealthy socialites for commissioned silkscreens costing upwards of $25,000 (in 1970s dollars!). The work I have pulled today, unidentified woman, is representative of another large group of portraits that depict everyday people that he found interesting or beautiful. In fact, Warhol is said to have loved people— their mystery, ability to transcend, and vulnerability.

Warhol was particularly fascinated with the idea of social equality, he is famous for saying “Now it doesn’t matter if you came over on the Mayflower, so long as you can get into Studio 54… Anyone rich, powerful, beautiful, or famous can get into Society.” [2] Indeed, Pop Art in general tended toward the idea of obliterating social boundaries and the camera functioned as a leveling device. Yet as inclined toward sociality as he was, Warhol also wore his BigShot constantly, allowing it to function as intermediary and so that he wouldn’t be confronted personally by the hoi polloi.

The Making of Unidentified Woman

Upon arriving at The Factory, a new sitter would be treated to lunch and libations before joining Warhol for an in-depth taped interview. Quickly, Warhol would move to the studio where women would typically have white makeup applied to the face to even their features and be wrapped in a cloth around the chest in order to establish a classical framework for the portrait. Warhol would often take as many as 300 Polaroid photographs in a single sitting in order to break through the persona and get to the real personality of the subject.

Once finished, Warhol would listen to input from the sitter before selecting the images. The Polaroid was then re-photographed in 35mm, printed as 8x10 inch acetates, and eventually enlarged to 40x40 inches in preparation for making a silkscreen. Warhol would instruct his assistants each step along the way, continually bringing color and detail back into the work. As much as Warhol attempted to identify the personality of the sitter through these sessions, he also would overlay this image as he would a blank canvas. Photography is unique in its ability to render both an absolutely realistic portrait as well as to present an opportunity, because of its chemical nature, for the artist to alter this visage in ways that are transcendent.

But this is getting ahead of ourselves to another aspect of Warhol’s practice and today we are looking at these Polaroid images as complete works in themselves. As opposed to the glamour of painted and silkscreened portraits, the Polaroid images are mundane, awkward, and intimate. Some have compared these to “selfies” in their similarity to photo booth images (and in fact Warhol used a photo booth prior to the BigShot).

WARHOL’S INCLINATIONS AND LEGACY AS PHOTOGRAPHER

In the end the question of whether Warhol was a photographer and if these images are fine art was even debated in the courts! In the early 90s, Warhol’s estate lawyer, Edward Hayes claimed ownership of 2% of the value of his estate as payment for legal services. The Warhol Foundation claimed the assets as archival and therefor valued lower than artworks whereas Hayes looked to increase the value of the estate by claiming them as original art works. One side valued the images at $1-5 per, while the other valuation was $80 million for the full set of 66,000 equaling approx. $1,200 per image.

Let us not, however, become mired in a conversation around value but instead appreciate the rare glimpse into a photographic process that truly captures the beauty and singularity of the medium. The camera’s propensity to be both a barrier and a social aid, the ability of the photographic image to transcend boundaries, allowing for a penetrating inspection of the subject, while also often belaying a deep introspection on the part of the photographer. In this way, Warhol’s work with photography stands apart from his use of other media and is integral to an understanding of his process as an artist.

1. Lombino, Mary-Kay. The Polaroid Years: Instant Photography and Experimentation. New York, Prestel Publishing. 2013.

2. A Brush with History: Paintings from the National Portrait Gallery. By Carolyn Kinder Carr, Ellen Gross Miles, and Margaret C.S. Christman. January 1, 2001. P. 208.