What Happens When You Go to School at an Art Museum

Most students have experienced a field trip to a museum at some point during their primary or secondary education. But how many students could call an art museum their home for five consecutive days during the school year? For two sixth grade classes from the UCLA Community School, the normal routine of getting on a bus to go to school in Koreatown was recently disrupted.

The Classroom-in-Residence program at the Hammer Museum, or CIR@H as we fondly call it, took place on March 3-7 for one sixth grade class and on March 10-14 for another. Each class spent five school days receiving arts-integrated instruction from their teachers, sketching and writing in the galleries for extended amounts of time, engaging in movement lessons, and getting VIP treatment from Hammer staff through presentations on museum careers and behind-the-scenes tours. After spending an arts-rich school week at the museum, it was difficult for the students—as well as the teachers and Hammer staff members, including myself—to go back to their old routines.

As the new assistant director of academic programs at the Hammer Museum, I had been greatly looking forward to implementing the second iteration of CIR@H ever since I found out I got the job in January.

CIR@H began in March 2013 as a pilot program developed by the Visual and Performing Arts Education Program (VAPAE) in UCLA’s School of the Arts, in collaboration with the Hammer Museum and two sixth grade teachers at the UCLA Community School. The program aims to inspire students to discover, investigate, and reflect on works of art through a variety of experiences, including observation, discussion, and kinesthetic and writing strategies. The pilot program was a huge success, and all partners were enthusiastic about giving two new classes of sixth grade students a similarly unique, immersive learning experience at the Hammer Museum this year.

Judging by this year’s journal reflections, stories, poems, and astute observations about works of art, it’s clear that we’ve converted many more 6th graders into art lovers.

And in at least one case, we gave a student the opportunity to better understand herself. Sandi Martinez wrote in her journal: “The thing that mostly sticks out for me from yesterday is the fact that I felt I was in those paintings from the gallery. Thinking about the paintings and their meaning helped me finally become me.” Sandi’s teacher, Janet Lee-Ortiz, said that because Sandi is normally quiet, the journal helped her to realize how deep and thoughtful her student is.

This ability to see a student in a different light in a new environment is an important component of the Open Minds Program, an education initiative on which the CIR@H format was based. Developed by Dr. Gillian Kydd in Calgary, Canada, the Open Minds Program allows teachers to take learning outside of traditional classrooms and into the community through immersive, week-long instruction in educationally rich sites such as museums, zoos, and nature centers. At the core of the Open Minds philosophy is the idea that learning is enhanced when you slow down and take the time to observe the world.

In CIR@H, this concept of slowing down was manifested in the Hammer Museum’s galleries. Students were challenged to spend 50 minutes with one work of art and just their journals, a pencil, and their own thoughts and ideas. As an art lover and museum educator, I’ve led and participated in long discussions about one work of art that have lasted as long as an hour. But any experience I’ve had with a single work of art that lasted over 30 minutes took place with adults or was guided by an instructor. When I first heard about the time allotted for students to sketch and write about art in the galleries without guided instruction, I admit to being skeptical about whether sixth grade students could sit in front of a work of art for that long.

I was pleasantly surprised. Not only did most students quietly and happily sketch a work of art for the duration of their allotted time in the galleries, but also many of their drawings revealed a keen attention to detail, and their writing reflections, such as Sandi’s, showed a deep sense of empathy.

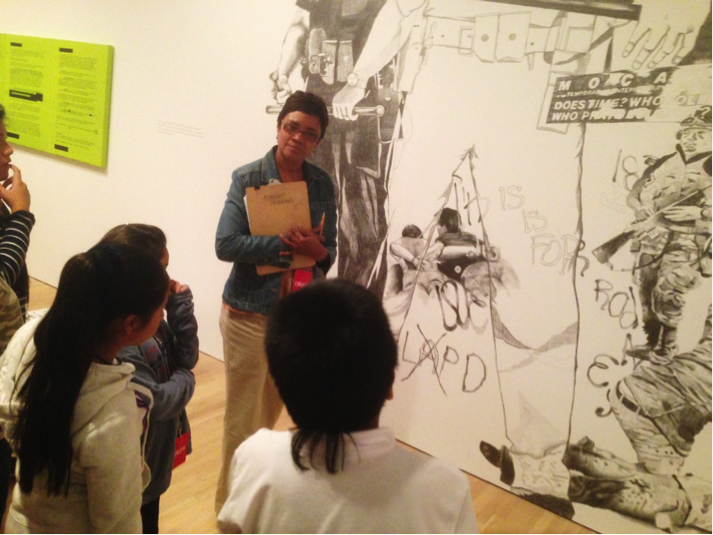

This empathy for figures depicted in art was exhibited most powerfully in poems inspired by a mural by contemporary artist Rikrit Tiravanija which is on view in the current exhibition Take It or Leave It. Tiravanjia’s work, untitled (up against the wall mother fucker), comprises a huge montage of overlapping images that depict the 1992 Los Angeles riots—or Los Angeles uprising, depending on whom you ask.

Teachers Janet Lee-Ortiz and Mike Nemiroff did not shy away from the complexity of teaching a politically charged event such as the 1992 rebellion in Watts. They spoke frankly about what it means to call the event a “riot” vs. an “uprising” and then invited students to select any person in Tiravanija’s mural and write from his or her perspective. Here are a couple of excerpts from students’ poems:

“In My Shoes” by Zeida M.

In my shoes I feel the pain in each photo I take on each corner.

I see people all around the street hurt by the police.

I hear the sounds of the police car and the helicopter around me.

I feel bad for all the people that had died and had been hurt.

I smell the smoking and drugs they have used.

I wish I had not seen that, I wish I wouldn’t

Capture that with my camera…

“In My Shoes” by Bryan P.

In my shoes, I need to be a better cop to protect everyone.

I see innocent people getting killed and beat up.

I hear innocent people sobbing from deaths.

I touch the cold breeze that feels sadness in my body.

I dream to protect people who are african, korean, and mexican.

I love the moment when people bring love in my vision.

I want to accomplish the goal I made.

I wish to be a hero that can protect anyone.

I understand how the people claim to be innocent or fugitive.

I care about the endangered people.

I must do what I must do to complete my goal…

Every single one of the 67 poems produced during CIR@H was powerful and heartfelt. As I read through poem after poem, I was impressed at students’ ability to capture the nuanced emotions that those present during this turbulent event must have felt. Could students have written such powerful poems in the traditional classroom? With incredible teachers like Janet Lee-Ortiz and Mike Nemiroff, probably. But with time away from their normal routine in a stimulating place like the Hammer Museum, when given the time to reflect and discover their own thoughts about art, I suspect it would have taken the students a few more drafts to get there. This is one of the many reasons I love when art is used to teach multiple subjects—art offers an immediate way in. --Theresa Sotto, assistant director, academic programs