Hammer Projects: Renata Petersen

- – This is a past exhibition

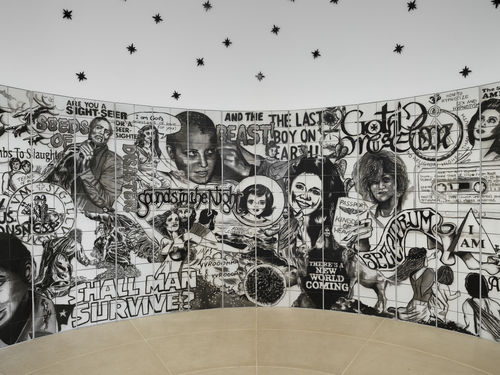

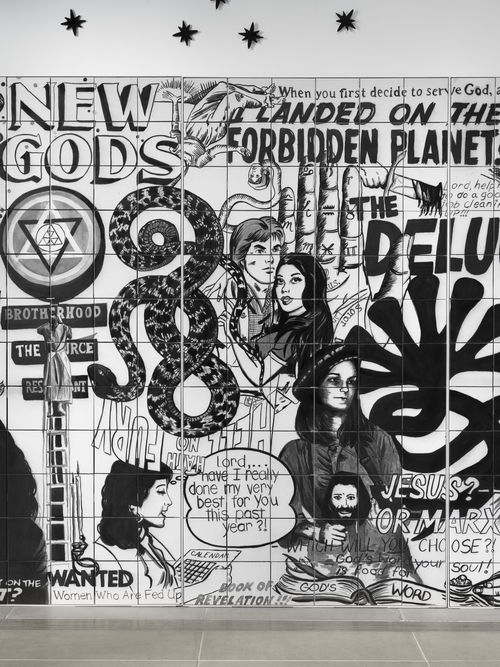

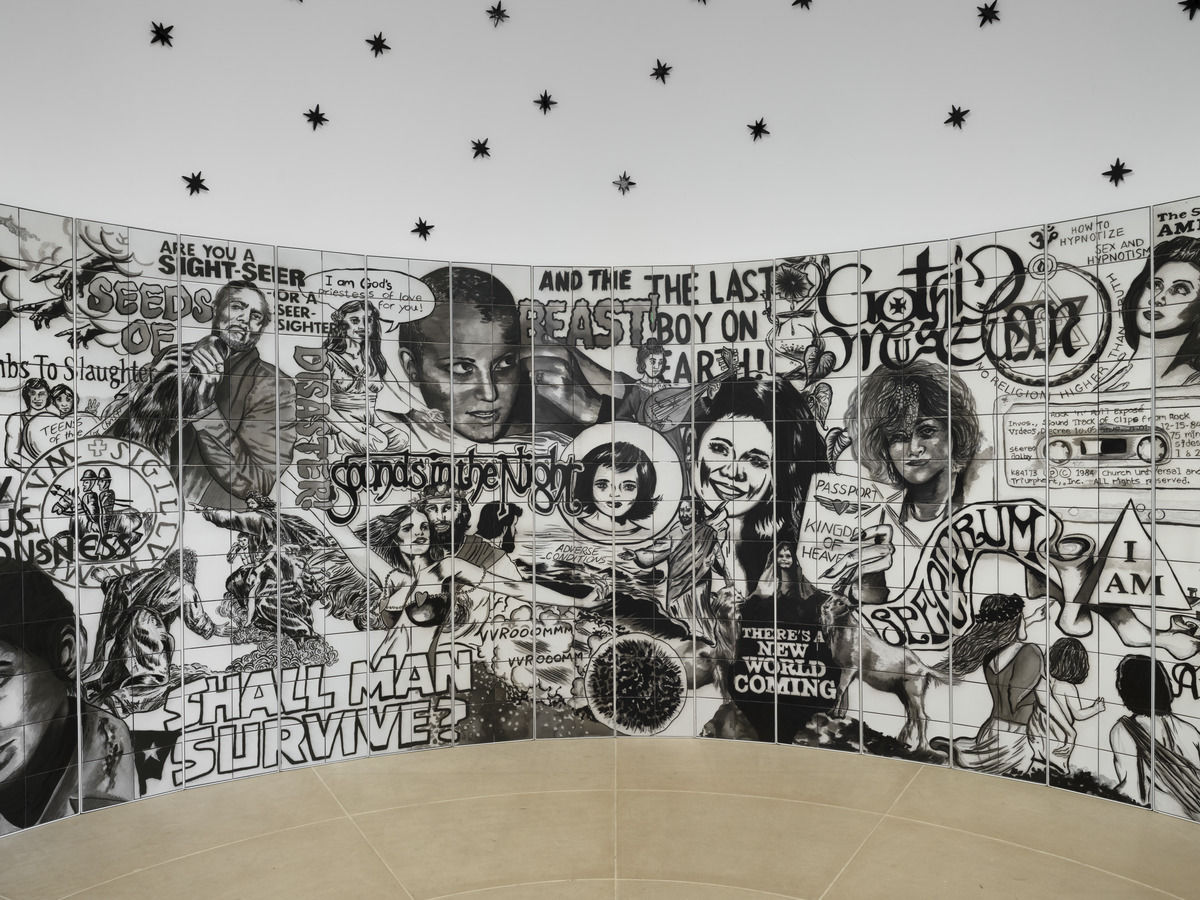

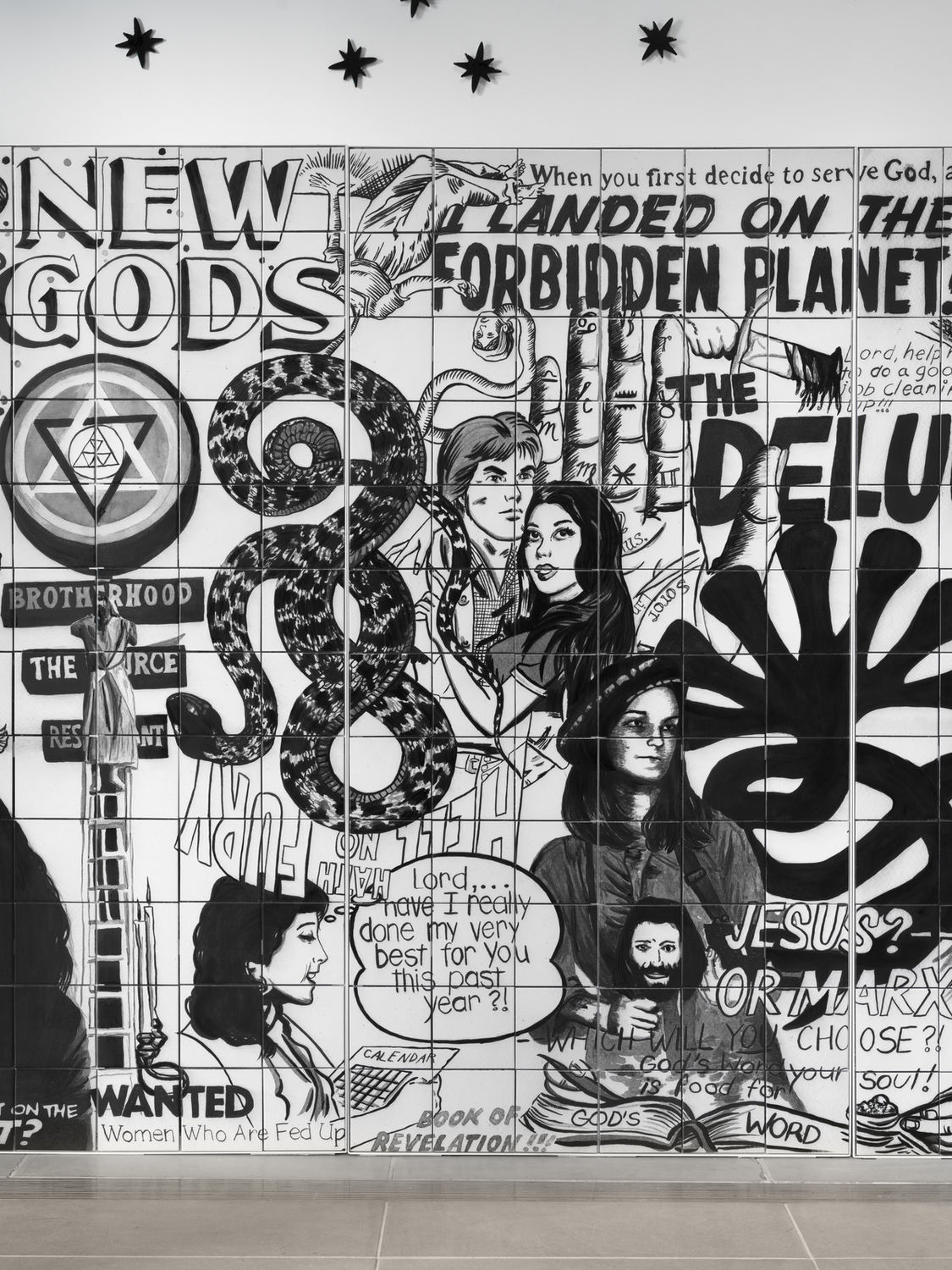

The source material for The Secret Gospel Church of Phallic Worship (2025) by Mexican artist Renata Petersen (b. 1993, Guadalajara, Mexico) is an aggregate of archival materials, including pamphlets, publications, photographs, and other ephemera, used by new religious movements and fraternal orders in California to spread their ideologies and recruit new members. The installation of comic-inspired drawings on ceramic tiles tells the story of groups such as David Brandt Berg’s The Children of God, the People’s Temple of Jim Jones, and Unarius (Universal Articulate Interdimensional Understanding of Science). The artist’s iconographic study recontextualizes the figureheads and doctrines of cults, secret societies, and fringe religious groups in a nonhierarchical, unified field. The title, The Secret Gospel Church of Phallic Worship, is taken from St. Priapus Church, a San Francisco-based religious organization founded in 1979. The still-active church preaches phallic worship and avoidance of sexual frustration to its congregation of mostly gay men. Such themes of sexual and libidinal liberation permeate the history unearthed by Petersen.

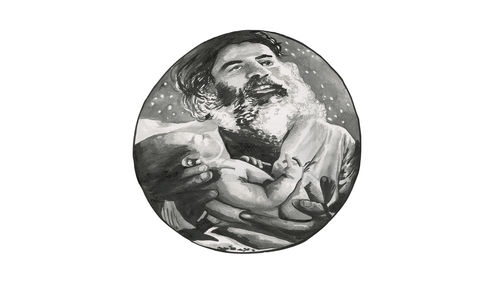

Enveloping the walls of the gallery, the installation recalls religious spaces such as the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy, where, in the early fourteenth century, Giotto di Bondone covered every surface with frescoes depicting the life of the Virgin and the life of Christ. Petersen’s church-like environment is similarly immersive and visually overwhelming, like many experiences in the twenty-first century—religious and otherwise. Petersen’s depiction of “sacred stories” of the twentieth century teems with polygamy, avarice, sexual exploitation, and the hippie aesthetics that characterize the California spirit of religious exploration. The Source Family’s infamous leader, Father Yod, appears at the installation’s center, a conceptual focal point that Giotto reserved for Jesus Christ. Petersen’s centering of Yod—whose vision extended beyond a spiritual commune and into psychedelic rock music, entrepreneurialism, and health food—draws a connection between the cult leader’s ambitions and the current atmosphere of lifestyle brands, social influencers, and upscale grocers that sell a way of life to their followers. Petersen’s role becomes that of hagiographer, chronicling the underbelly of contemporary religious thinking and documenting new-age icons that might otherwise be forgotten.

Hammer Projects: Renata Petersen is organized by Aram Moshayedi, independent curator and former Robert Soros Senior Curator, with Nyah Ginwright, curatorial assistant.

Essay

By Aram Moshayedi

With The Secret Gospel Church of Phallic Worship (2025), Mexican artist Renata Petersen assumes an art-historical responsibility. Fundamentally engaged with the question of visual literacy, or how readers extrapolate meaning from pictures, the artist represents a history of new-age religions in California from the 1920s to the present. Artists have long been tasked with illustrating religious texts and histories, but Petersen’s approach digs into the underbelly of faith-based belief systems, depicting a subculture that has become synonymous with exploitation and fear. Petersen’s installation of drawings on ceramic tile resembles the pages of a comic book, a popular visual and literary form that presupposes its audience’s sophisticated understanding of text and image.

Comics occupy an unsettled position within art history. The negative biases toward comics (and one might add religious cults) likely have been a catalyst for artists to embrace them. For its part, the Hammer Museum has contributed to efforts to validate the art of comic books in the development of American visual literacy. In 2005, the Hammer and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, presented Masters of American Comics, a sprawling exhibition of over nine hundred objects that addressed the immeasurable impact comics have had on contemporary visual culture, despite having been relegated to the status of “a subtext in the history of art.”1 In 2009, the Hammer exhibited The Bible Illuminated: R. Crumb’s Book of Genesis, a five-year undertaking by the famed cartoonist to illustrate the entirety of the first book of the Old Testament. The two exhibitions are part of a relatively short list of shows in art museums dedicated to comics, despite their influence on innumerable visual artists working today. Though the Hammer’s presentations focused exclusively on the apparent American mastery of the form, Palestinian American literary critic and scholar Edward Said asserts in his introduction to Joe Sacco’s anthologized series Palestine that comic books are a “universal phenomenon [that] seem[s] to exist in all languages and cultures.”2

The American Pop artists of the sixties are credited with bringing comic aesthetics into a fine-art idiom, and the influence of comics is apparent in the more recent work of Los Angeles artists Raymond Pettibon, Mike Kelley, and Jim Shaw, to name a few. Ad Reinhardt, Philip Guston, Dorothy Iannone, and Öyvind Fahlström come to mind as artists working internationally in the twentieth century at the apex of this intersection. Kerry James Marshall, Chitra Ganesh, and Trenton Doyle Hancock are contemporary inheritors of this legacy, while artists such as David Shrigley, Olav Westphalen, and Pablo Helguera summon in their drawings cartoon-like scenarios that are both humorous and critical of the world that surrounds them. If the related form of caricature is considered, the historical precedence extends to the political satire of Honoré Daumier and his nineteenth-century contemporaries.

Petersen’s source material for The Secret Gospel Church of Phallic Worship is an aggregate of archival materials, including pamphlets, publications, photographs, and other ephemera, used by fringe religious groups in California to spread their ideologies and recruit new members. Her approach is almost anthropological in nature, as she analyzes the imagery from groups such as David Brandt Berg’s The Children of God, the People’s Temple of Jim Jones, and Unarius (Universal Articulate Interdimensional Understanding of Science) in a nonhierarchical, impartial manner. Collected together, the images offer an iconographic study of modern cults, secret societies, and new religious movements. The ceramic tiles recontextualize the doctrines of these groups in a unified field, binding them together as plot points in an otherwise untold story. The title, The Secret Gospel Church of Phallic Worship, is taken from St. Priapus Church, a San Francisco-based religious organization founded in 1979. The still-active church preaches phallic worship and avoidance of sexual frustration to its congregation of mostly gay men. The artist frequently encountered similar themes of sexual and libidinal liberation in her research.

Petersen’s ceramic tiles envelop the walls of the Hammer’s Vault Gallery, recalling religious spaces such as the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy, home to Giotto di Bondone’s early-fourteenth-century frescoes depicting the life of the Virgin and the life of Christ. Petersen’s church-like environment is immersive and visually overwhelming, like many experiences in the twenty-first century—religious and otherwise. At the same time, it recalls Giotto’s kaleidoscopic vision for his own historical moment, in which he covered every surface of the chapel with frescoes in order to educate and inspire the masses. Petersen’s depiction of the “sacred stories” of the twentieth century teems with polygamy, avarice, sexual exploitation, and the hippie aesthetics that characterize the California spirit of religious exploration. The Source Family’s infamous leader Father Yod—whose vision extended beyond a spiritual commune and into psychedelic rock music, entrepreneurialism, and health food—appears at the installation’s center, a conceptual focal point that Giotto reserved for Jesus Christ. Petersen’s centering of Yod amplifies the ways in which the ambitions of such figures persist in the current atmosphere of lifestyle brands, social influencers, and upscale grocers that sell a way of life to their followers. Her tale of how we got here proposes an alternate vision of the Creation myth. Through an amalgamation of new-age icons and belief systems, she recounts a history of the relationship between vulnerability and religious faith.

Petersen’s first step in translating her source material is drawing, thus evoking the art-historical definition of cartoon, a term that originated in the Middle Ages to refer to preparatory sketches made in advance of paintings and frescoes. While drawing serves a preliminary function for Petersen, it is also her signature technique, which she often employs alongside other artisanal processes such as glass blowing and ceramics. She uses digital printing and hand-painted embellishments to render her drawings on ceramic tiles. The tiles afford a shift of scale from intimate to architectural. Materially, the tiles also impart weight and permanence to an otherwise fleeting history. In its use of both artisanal and digital processes, the work is as refreshingly anachronistic as it is contemporary. For Petersen, the cartoon is a potent form that allows for associative comparisons and visual thinking to emerge in a real-time process that evokes history and contemporaneity simultaneously, situating audiences in the Middle Ages and the twenty-first century. Like Giotto and R. Crumb before her, Petersen understands the role that images play in the communication of power and ideology. Petersen’s graphic style is comparatively restrained and monochromatic, and her work is unbound by the conventional framing devices that separate scenes in chapels and comic books. Petersen’s sources and ambitions are also more polyamorous than her predecessors’. In her narrative, the disparate stories and historical voices flow and merge into one another along a continuum. All the while, Petersen assumes the role of hagiographer, chronicling a history of contemporary religious thinking that might otherwise be forgotten.

1. Ann Philbin and Jeremy Strick, “Directors’ Foreword,” Masters of American Comics (Yale University Press, Hammer Museum, and The Museum of Contemporary Art, 2005), 10.

2. Edward Said, “Homage to Joe Sacco,” in Joe Sacco, Palestine (Fantagraphics Books, 2015), i.

Hammer Projects are single-gallery exhibitions highlighting the work of contemporary artists from around the globe, often presenting new work at a pivotal moment of an artist’s development. Ongoing since 1999, Hammer Projects is a signature series within the Hammer’s exhibition program.

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation. Lead funding is provided by the Hammer Collective. Major support is provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy, with additional support from the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Department of Arts and Culture.

Special thanks to Cerámica Suro and Amaury Vergara.