Hammer Projects: Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

- – This is a past exhibition

The paintings and multimedia installations of Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi (b. 1980, New York City) offer a meticulous interplay of line and color as they delve into the dynamics of identity, race, patriarchy, and power. Born to activist parents, including a father who endured a thirty-year exile as a South African freedom fighter, Nkosi spent her formative years between the Zimbabwean capital of Harare and the South African city of Johannesburg, where she currently lives and works. Nkosi’s artistic practice meditates on these Afro-diasporic lines of flight, with her conceptual and formal lexicon attuned to modes of abstraction and assemblage that are always changing. In Nkosi’s Gymnasium (2019–22) series, gymnasts, scorekeepers, judges, and spectators inhabit pared-down spaces characterized by sleek geometric abstraction. Notably, the figures are flattened, and their faces are devoid of distinguishing features. Throughout the series Nkosi skillfully captures emotional moments of humanity and tenderness rarely attributed to gymnasts—bodies stretching, embracing, and sitting in quiet contemplation between floor exercises.

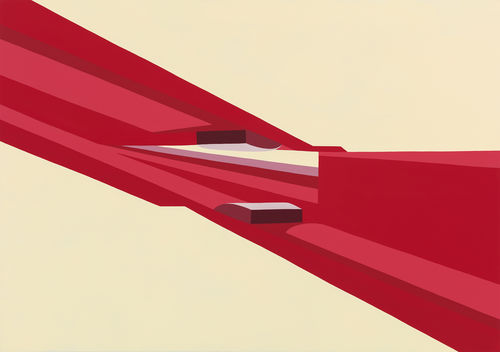

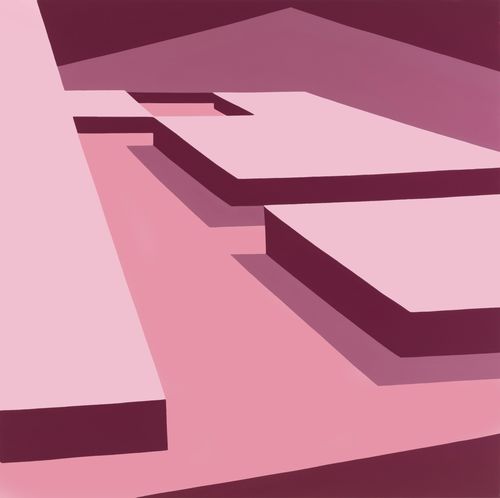

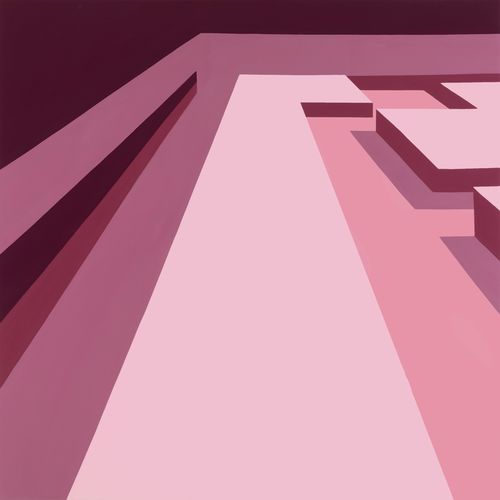

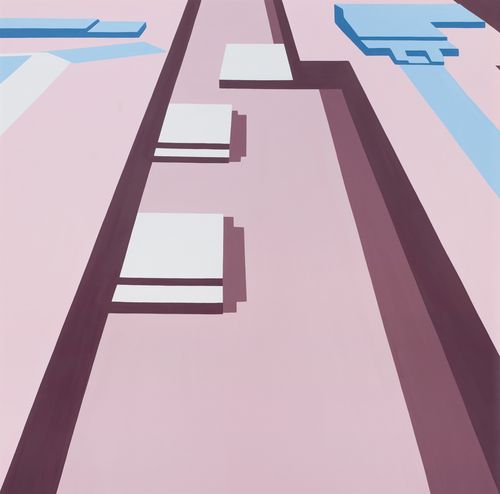

In her most recent work, ARENA V (2024), Nkosi extends her study of the social and psychological experiences of Black gymnasts. In her view, these individuals often grapple with maintaining their personal identities amid public scrutiny as symbols of excellence. Yet the gymnast is not alone in this balancing act; Nkosi draws parallels between the athlete and the artist, both facing the challenges of performing, flailing, failing, being judged, and ultimately seeking freedom from these assumptions. She initiated this introspective process in her Arena (2021–) series, close-cropped paintings that contemplate line, form, geometry, and architecture. ARENA V synthesizes these concepts beyond the canvas into a multimedia installation, with Nkosi extrapolating her experimentation into the built environment. She employs her familiar visual language of geometric abstraction, measured figuration, and a softened yet rich color palette to explore the inner lives of subjects at the threshold of performance. The true allure is in the way ARENA V transforms the Hammer’s lobby into an architectural portal, prompting questions about the subtle gains achieved by manipulating the details of people and places. In 2012 the Nigerian novelist Ben Okri delivered a lecture in South Africa in which he compared the quest for freedom to playing a game that isn’t ours but rather the game of others. One way to get free, Okri argued, is by telling of “the real magical Africa that we don’t see unfolding through all the difficulties of our time, like a quiet miracle.” ARENA V, in this context, offers glimpses of that untold story.

Hammer Projects: Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi is organized by Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi, curatorial associate, with Connie Butler, director at MoMA PS1 and former Hammer Museum chief curator.

Essay

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi interviewed by Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi is not necessarily seeking specificity in her multimedia artistic practice. However, she’s not generalizing either. Although the strategies and degrees of abstraction evident in her paintings may make her scenes appear generic, the ideas and concepts are not detached from lived experience. Towing this abstract line—both concrete and metaphoric—animates Nkosi’s analytic vis-à-vis the Black female athletes in her work. Nkosi concedes that she adopted “gymnastics as a metaphor for larger structural and social dynamics.”1 But if we examine the portrayal of faces in Nkosi’s work, an undeniable diversity emerges, implying that this, too, might be a metaphor under scrutiny. In fact, the Black feminist scholar Hortense Spillers has noted that “the body, in its material and abstract phase, [becomes] a resource for metaphor.” The body ultimately speaks for more than just itself by virtue of the metaphors we write into it, whether through painting or video. Spillers reminds us that how we mark up this metaphor determines the cultural meanings we ascribe to the body. But she also distinguishes that “before the ‘body’ there is the ‘flesh,’” which eerily resonates with the featureless faces in Nkosi’s paintings. The varying shades, textures, and details within Nkosi’s portrayal of Blackness speak to abstraction as a defining ethos of Black life. And yet Spillers expressed skepticism about whether the formal movements of Blackness might shift the “primary narrative” of flesh away from violence and closer to the human body.2 Nkosi wants to trouble this doubt. What needs to be inscribed on Black flesh to acknowledge the humanity and bodily autonomy often denied to Black people? And is it even a worthwhile enterprise? These concerns shape the conversation with Nkosi that follows.

Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi: So let’s begin with your Arena series [2021–] as it has evolved over time. The prior Arena works were paintings focused on the spatial terrain of the gym. I imagine this move from canvas to the built space of a museum provided fertile ground to extend the Arena series. Can you speak to why you chose this series for your Hammer Project, ARENA V [2024]?

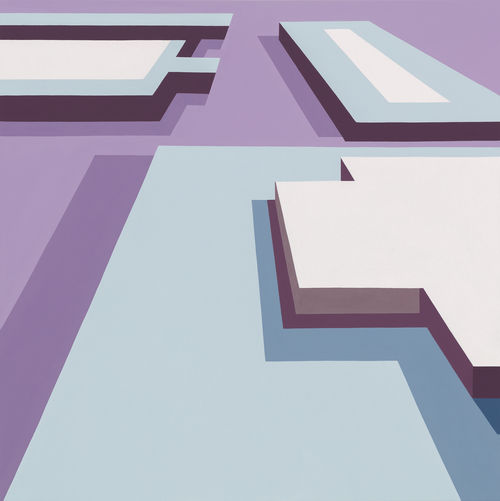

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi: Conceptualizing and designing this installation felt like a return to the early ideas I was working with in the Gymnasium series [2019–22]. Gymnasium grew largely out of my interest in the architecture and geometry of sports arenas. And when I introduced figures—gymnasts, judges, spectators—it took on another life. But the architecture was always of central importance. So when I was presented with the idea of working in and with the physical space of the entrance to the museum, it became an opportunity to treat the project as an architectural consideration.

In the installation at the Hammer, I am superimposing a representation of the architecture of the gymnastics arena—or parts of the arena—onto the museum’s architecture. It is a representation of architecture interacting with an actual architecture. So through that superimposition a third space is created. Through the sculptural installation on the museum floor, the work comes into the three-dimensional space of the museum and then extends back or recedes into the walls, creating the illusion of expansive space. This new space is both imaginary/illusory and real.

To have the gymnastics floor spill onto the floor of the museum and to be something that viewers can actually walk on, jump on, invites visitors to become involved in the artwork. Especially because it’s a corner of the gymnastics floor. A very loaded position, psychologically, because it is the point where the gymnast starts the diagonal tumble. It is a cheeky invitation, maybe, because you can’t actually go in, but it is an invitation to the viewer to imagine themselves in the space of the arena. That small piece of a texture in the visitor’s world that invites them to imagine that they could be the person performing in that space. The identities of the spectator and the performer are momentarily merged. And by offering the visitor or viewer the opportunity to occupy (physically, sensorily, and psychologically) the same position as the gymnast, the work aims to blur the lines between spectator and performer. It is also an invitation for the viewer to participate in a process of remembering the body—the vulnerable, feeling body—as the central point around which elite competition, mass entertainment, and other similarly monetized constructs are built and sustained.

The decision to include sound in the installation grew out of thinking about architecture in this more expansive way. I was thinking about the creation of space and realized that an important element in creating this multidimensional world could be introducing an aural perception of space. The sounds of the arena are so distinctive and evocative. I wanted to re-create a dreamlike version of this, a sort of muted version of the cacophony of competition. I see it as another architectural element to support the illusion of the arena.

IO: You know, the first work by you that I saw was your video Suspension [2020], which zeroes in on the gymnasts’ faces in all their vulnerability and affect before their floor routine commences. Considering that the sound score for Suspension wasn’t associated with what one hears in a gymnasium, I appreciate that you are attending to what people might consider the noise of the sporting arena. Modern architecture has sought to eliminate these acoustics, treating them like detachable echoes.3 I’m glad you’re thinking intimately about manipulating the sonics of that built space—the arena—for the Hammer installation. Circling back to the gymnasts in Suspension, I’m interested in how you approach the face across video and the vacated profiles in your paintings. It raises questions about the ethics expressed through the face and by extension the body. You have talked about the pressures placed on athletes to be exemplars of society. How does the face figure into that line of thought, if at all?

A related point: I’m not a fan of Emmanuel Levinas, but I’m drawn to how Judith Butler, through Levinas, describes the face as a displacement or catachresis for other body parts and vocalizations. At the same time Levinas is quite dismissive of South Africa, remarking that it is a “dancing civilization,” whereas “the Bible and the Greeks present the only serious issues in human life.”4 In a way Levinas’s face is an interpretation of humanity not open to all. Although representation won’t get us free from these assumptions, I do wonder whether the variable treatment of the face from Suspension to the paintings articulates a spectrum of aesthesis—feelings, senses, perceptions—that counter the history of anti-Black violence within modernism.

TNN: In all my figurative work I’m making decisions about how much detail to give, decisions that have to do with ideas of the universal and the specific. This is true whether it’s in video works; in paintings of gymnasts or athletes in which the faces, the facial details, are not present; or in my series of portraits, called Heroes [2013–], in which I paint particular people’s faces in detail and then fade these details away through wiping and veiling.

The question of faces for me is about narrative. It’s about stories, histories, interpersonal relationships. When I see a face I don’t recognize, I wonder who that person might be, what their story is. I look for clues in their expression. When I do recognize somebody, I think about stories I have heard about or from that person, or I question who they are in relation to my story. So in both cases there is a story or the provocation to storytelling implicated in a face.

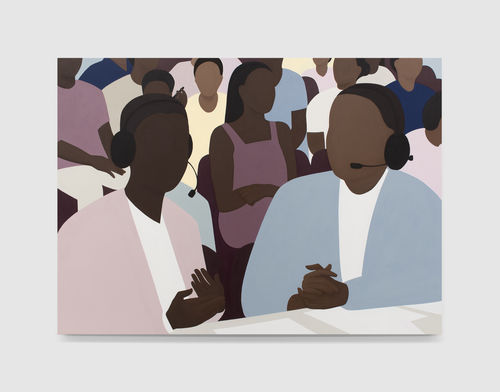

When there are these faceless people, like the figures I have been painting in the Gymnasium and Stadium [2023] works, to me it is still about identification and provocation to story. Butler and Levinas’s idea that parts of the body—a shoulder, a back—can be said to “scream” or “cry,” giving those inarticulate parts of the body the power to communicate we usually ascribe to the face, certainly resonates for me. I find that the faceless figures in these two bodies of work ideally take on a level of articulacy or a sense of character through their postures, or body language, that is different but not necessarily inferior. Identification happens in the affect that is displaced from the facial features onto the body—the gestures, the relationships between bodies, the ways that the figures are interacting. Which is also about story. So here, in this work, it is the story of this group of gymnasts, this group of people and their various relationships.

If there is a difference, I think it is that where you do not see a particular face, it is more of an invitation to the viewer to identify, to place themselves in the scene. It functions in the same way as removing the geographic or historical context from the work. The facelessness and lack of context markers (beyond the “arena”) invite viewers to make up the rest of the story and to put themselves into it.

With regards to the video Suspension and the question of “exemplars,” as well as the humanizing power of the face in the context of anti-Blackness, what I set out to do with Suspension was to make a piece about the psycho-emotional space that athletes inhabit before they perform. Through watching competitions and interviewing gymnasts and reading their testimonies, I started to understand the complex nature of that space. It’s not as simple as “psyching yourself up” for something. There’s a wide spectrum of thoughts and feelings that rush through the mind. Thoughts and feelings one finds oneself suspended in. There are the ways of perceiving oneself—from both an internal and an external perspective—and imagining the outcome or replaying performances of the past that all make up to this intense period, or space even, that the gymnasts occupy in those few moments between standing up, being announced, and presenting themselves as ready. The finished piece turned into a very human study. I think that is why it seems to resonate with a lot of people. The repetition of the faces of the gymnasts, the slow accretion of expressions, of deep breaths, of vulnerability and emotions (nervousness, excitement, determination, doubt), all seen in close-up, becomes a study of humanity under inhuman pressure. And the fact that I chose to work with footage of Black and Brown athletes, who are also girls and young women, is crucial. Gymnastics has a very racialized and racist history. Its modern roots are closely bound up with white supremacist ideologies; it was promoted internationally as a tool for white dominance. So for me the question was also: What does centering the complex inner world of these young people do to counteract the anti-Black violence that remains in the arena, in the sport, and in society more broadly? What power is found (and resisted) when we immerse ourselves in each other’s stories?

IO: The insights from [Hortense] Spillers align with your exploration of the face as a metaphor and invitation for connection. I would not describe the faceless gymnasts as “ungendered” or “claiming . . . monstrosity,” but rather their neutral and almost expressionless features provide a canvas for viewers of any gender to interpret these fleshy, supposedly female faces as a “text for living and for dying” and perhaps even for naming.5

This idea of a text segues into the evolving significance of geometric abstraction in your work. In the Arena series, the initially unoccupied abstract architectural paintings eventually come to life with people. Prior to the emergence of figures, there seems to be a latent trajectory. Theater scholar Mwenya B. Kabwe described your work as a “journey from geometry to architecture, with the insertion of a figure.”6 I am intrigued by the role abstraction plays in this journey, particularly as it navigates between the spaces you are mapping out and the people you introduce into these spaces. Your statement about experimenting with the minimal amount of information needed to render something “legible” is notable. How does this approach reflect your thoughts and ideologies regarding abstraction as a strategy? Furthermore, how does the intentional withholding of information or the gesture of abstraction contribute to the streamlined depictions of both places and people?

TNN: In my own thinking about architecture and geometry in painting—or in 2D representation more generally—I am interested in the moment when I start to read something as architectural, as opposed to just geometric. And how the mind’s perception can sort of slide between the two, that sliding perception between representative shapes and the purely abstract. It is more of a game that I am playing than an interest in any particular ideology. It is an ongoing experiment, something I am trying to figure out in terms of perception and meaning. And part of that experiment is looking at what happens when a human figure is inserted into a geometric space. Does the geometry become architecture? And without a human figure, do architectural shapes lose some of their meaning? Some or all of their meaning?

I guess this line of investigation has something to do with the idea that architecture is meaningless unless or until there is a human interaction with it. So perhaps if I am tending toward any ideology, it is for architecture to always have at its core some kind of humanity or some kind of humanism or humanistic intention. I think that comes out of a history of my own, of looking closely at architecture that was created to glorify or uphold inhumane systems. In my very earliest work as a painter, I focused on architectural portraits (that was how I thought of them), specifically of buildings and monuments created under apartheid. I was interested in how I could pare down these shapes to essential forms, to see what the essential forms would say about the ideologies that informed them.

IO: I have always thought of your work as considering architectural form but with the human as the primary concern within that abstract framework. Introducing ideology into this ensures that architecture doesn’t become self-absorbed, almost as though your questions of geometry and humanity reveal the limits of modernist forms—e.g., line—when it encounters real life.

I am curious about whether this historical context was at the forefront of your mind during your recent solo exhibition in Amsterdam, where the De Stijl group popularized geometric forms to document “absolute reality.” Considering the trajectory of geometric abstraction through Europe in the early to mid-twentieth century—with Bauhaus key to its dissemination—it appears that working at the scale of installation was a natural progression. Our curatorial discussions and initial proposals considered not only painting but also how we could materialize abstraction through the lobby’s architecture, incorporating stage design and even performance. How do you situate the sprung floors in the installation at the Hammer within this historical and contemporary lineage?

TNN: While I have always found resonance and even inspiration in the visual directness and straightforwardness of the De Stijl artists, I have never been as intrigued by their interest in expressing some essential or absolute truth. Those ideas are, for me, quite foreign at this point, because I am more concerned with that which is not absolute. I am concerned more with that which lies in the shifting, dynamic space of contingency relationships. How people are contingent on one another. This is something very clearly expressed in African humanist philosophy. My work is more about relationships—relationship of performer to spectator, gymnast to judge, gymnasts to one another. Gymnasts to themselves. For me the connection between the experiences of the gymnast and the artist has always been a crucial part of this exploration. Both must perform themselves before a scrutinizing gaze. Both must attempt the impossible and fail before the gaze of the judge, the viewer. Through implicating the viewers and involving them in the work, as I am doing in this installation, I am interested in complicating these roles, even reversing them.

I have always thought about the arena as both a compelling physical environment and a metaphor for a psychological space. The psychological space of performance. Of being watched, of being judged, of being witnessed. Of dealing with expectation and scrutiny. That moment of being about to do something—whether it is your “best” or just what you know to do. Or just to be, actually. Just to be. That is so important for me, especially in considering this particular work. Because, counter to all the ideas around performance and expectation that are conjured by the architecture of the arena are the actual professional gymnasts, the figures, who are at rest in this image. They are not performing; they are just sitting. They are anti-performing. It is not even only that they are at rest; they are just being; they are outside of their professional roles completely. The one looks like they are dreaming, and the other one is telling a story, and there is listening going on. Perhaps, for this moment at least, they have abandoned the expectations around their roles, the desires and expectations of the arena and of the sporting or entertainment industry, completely. And here they are, front and center, in their abandon.

Notes

1. Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, in Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi: Gymnasium (Johannesburg: Stevenson, 2020), 38.

2. Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (Summer 1987): 66, 67.

3. Jonathan Sterne, “Space within Space: Artificial Reverb and the Detachable Echo,” Grey Room, no. 60 (Summer 2015): 111–12.

4. Emmanuel Levinas, “Intention, Event, and the Other” (1989), in Is It Righteous to Be? Interviews with Emmanuel Levinas, ed. Jill Robbins (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001), 149.

5. Spillers, “Mama’s Baby,” 68, 80.

6. Mwenya B. Kabwe, “Gymnasium, at a Time Like This,” in Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, 7.

BIOGRAPHY

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi (b. 1980, New York) lives and works in Johannesburg, dividing her time between studio work, performance, and navigating the field of art as social practice. Nkosi presented Equations for a body at rest at East Side Projects and across public spaces in Birmingham, England, as part of the 2022 Commonwealth Games. She has had solo exhibitions at the Africa Center, New York (2019), and Seedspace Gallery, Nashville (2017). Notable group exhibitions include the 15th Sharjah Biennial, UAE (2023); Eli and Edythe Broad Museum of Art, Michigan State University, East Lansing (2023); Naughton Gallery at Queen’s University, Belfast (2023); CHAMPS, Granville Centre Art Gallery, Cumberland, Sydney (2023); Orlando Museum of Art, Florida (2023); Soho Studios, Vienna (2022); Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, Cape Town (2022); deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, MA (2022); FRAC Poitou-Charentes, Angoulême, France (2021); Norval Foundation, Cape Town (2021); Aga Khan Museum, Toronto (2020); Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw (2018); Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (2017); and National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Harare (2016). Nkosi received the Philippe Wamba Prize in African Studies (2004) and the Tollman Award for the Visual Arts (2019). She obtained her BA from Harvard University (2004) and her MFA from the School of Visual Arts, New York (2008).