Hammer Projects: noé olivas

- – This is a past exhibition

Using materials that reference Southern California's rich cultural landscape and visual vernacular—from car parts and motor oil to broken concrete and soil—Los Angeles–based noé olivas (b. 1987, San Diego, occupied Kumeyaay land) creates sculptures, prints, and performances that investigate the poetics of labor, specifically its relationship to leisure and liberation. Many of olivas’s sculptures are comprised of his own customized forms—hybrid assemblages in the Chicanx spirit of rasquachismo that question traditional divisions between the aesthetic and the utilitarian. Playing with and reshaping objects that speak to the circuit of labor between Southern California and the US-Mexico border, olivas explores his experience growing up in an immigrant working-class family, often incorporating elements from his personal archives into the found and utilitarian materials of his sculptures.

Let’s Pray is a site-specific installation inspired by the forms and conceptual gestures of the toolshed, which olivas sees as a spiritual space of creation and community-building. The installation features a new body of works in ceramic, print, neon, and sound. Crafting his framework within the abolitionist philosophy and practices of Crenshaw Dairy Mart, a South Central and Inglewood art hub co-founded by olivas, the artist enacts a meditation on the power of collective care, craft, and healing through collaboration.

Learn more about noé olivas by downloading the free Bloomberg Connects museum guide. Watch an artist profile, read an essay about the work, and enjoy guides to other Hammer exhibitions—plus content from more than 50 other museums worldwide.

Hammer Projects: noé olivas is organized by Vanessa Arizmendi, curatorial associate.

Essay

By Vanessa Arizmendi

"All spirits seat themselves on the center of the sign as a source of firmness." —Anonymous

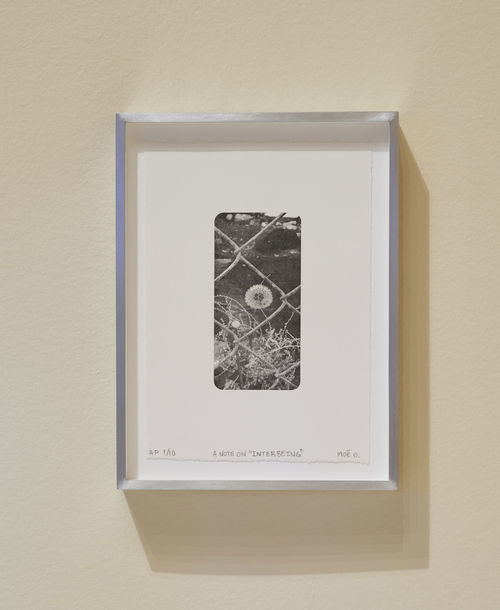

noé olivas’s practice is a meditation on the power of bodies at work, at rest, at play, and in prayer. Deploying what he calls a “poetics of labor,” olivas mines the rich visual vernacular of a distinctively Southern California landscape—including car parts, motor oil, broken concrete, and soil—to build an aesthetics of the utilitarian, one that aims to trace and celebrate the invisible networks of labor across this region’s working-class, immigrant, and artistic communities. For olivas, the imperative of social and spiritual liberation finds potentiality in the most quotidian of scenes: the treads of a truck tire pressed into thick terra-cotta; the rust on his father’s wheelbarrow clashing with its brand-new chrome chain steering wheel; a dandelion blossoming behind a chain-link fence.

In 1967, in his self-published newsletter One to One: Quarterly Report on Aspects of Creativity, the California artist, social worker, and teacher Noah Purifoy wrote: “Art can become a new thing when and if it is virtually and willfully used as a symbol through which someone becomes better. Art itself is of little or no value if in its relatedness it does not effect a change. We do not mean a change in appearance of physical things but a change in the behavior of human beings.”1 A similar necessity shapes olivas’s philosophy of creative action. For him, art does not lie solely in the realm of the symbolic, dictated by tastes that themselves are invariably shaped by the (classed and racialized) structural power of the market. Rather the kinetic energy of artistic manifestation, and its imperative in our communities, lies in its ability to make concrete change in the world, whether in the classroom, the gallery, the community center, or the realm of the spirit. What art does is work.

Thus the signifiers of everyday labor become their own kind of mantric language in olivas’s sculptures, performances, and works on paper. His early assemblage works, in particular, embody an ethos that one could site somewhere between Chicanx rasquachismo and what David Hammons called Delta Spirit—what has become a unique tradition of Southern California assemblage through Black and Brown migration across the southern United States.2 A low and slow heritage passed down through the car clubs, a cheeky sparring between form and function, productivity and play. olivas’s customized forms enact an alchemy of constructed relation perfected through the artist’s hand.

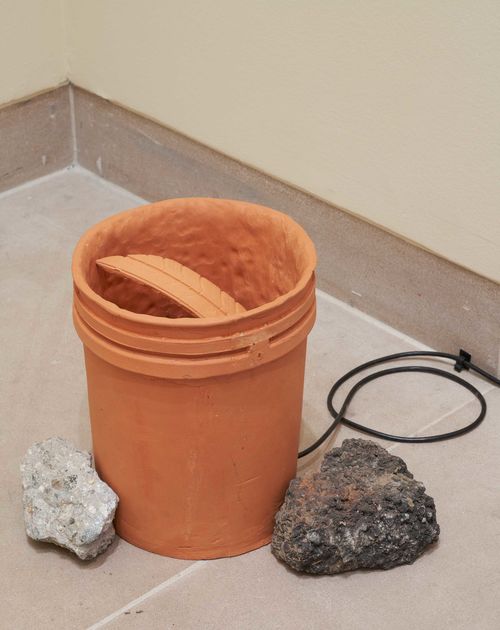

For his Hammer Project, Let’s Pray (2022), olivas takes inspiration from the instruments and conceptual gestures of the toolshed, which he sees as the spiritual space of creation. In the dynamic space of the Hammer’s Vault Gallery, he cultivates his familiar play with texture and materiality through a juxtaposition between earth and metal, industrial and handmade. At the center of the installation is A prayer for change (2022), an assemblage sculpture incorporating the original camper shell from the 1987 Ford Ranger (“la trokita blanca”) used by the Olivas family for road trips across the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Also included are two series of ceramic planters that take their forms from the artist’s lexicon of the everyday, in this case, Stacked tires (2021) and 5 gallon bucket (2021). Together with Morning movements (2021)—an original sound piece replicating construction sounds heard near olivas’s South Central home—the sculptures create an environmental experience reminiscent of the gardens and front yards of Los Angeles’s Black and Brown neighborhoods, sites in which citizens are allowed to have a hand in the production and transformation of communal space.3

olivas’s gestures of material transcendence and transfiguration are what catalyze the potential of his assemblage works. Another recurring figure in his practice, the Sleeping Mexican, makes its own sporadic appearance in the installation, this time molded in liquid concrete (the artist has previously cast these figures in plaster, clay, and dirt). In the cool shadow of olivas’s altar to creation, the Sleeping Mexican—representing a cruel stereotype symbolic of the very real violence faced by working-class Latinx communities, including Mexican and Chicanx immigrants—becomes a figure in gentle repose, like a seedling finding life in the earth from which he was cast. This is olivas’s personal idiom of transcendence through craft.

It’s interesting to note the motions of circling and crossing that act as their own kind of prayer in olivas’s work. Performances such as Heading West (10W, March 25, 8 am) (2019) highlight the artist’s interest in modes of transportation (cars, bikes, skates) as referents to Black and Brown histories of migration and placemaking more generally and the circuit of labor between Southern California and the US–Mexico border specifically. Since 2012 olivas’s sixty-three-square-foot rolling sculpture domingo, composed of his 1967 Chevrolet bread truck, has also brought mobile exhibitions and art projects to neighborhoods all over Southern California. Many of these performative works draw on his own familial legacies, particularly the early years of his adulthood spent working landscaping jobs in the San Diego area with his father before entering art school. As in the case of Reunidos (2019)—in which he used paper laid on asphalt to collect the markings of his stride while wearing a pair of custom leather work boots made into roller skates—olivas’s literal physical tracing of space and time serves as both a mapping of site and a consecration of the land.

At the center of A prayer for change, which is viewable in the round, olivas enlists his familiar friends, the wheelbarrow and shovel, to demarcate the spiritual center of the exhibition. The camper shell, which he has likened to a spaceship, is a reminder of these intimate histories of movement and migration, a worldview and political reality beyond the walls of the gallery. The effect is the creation of an ambulatory space in which the viewer is encouraged to complete their own rotation across the floor while contemplating the sculptural forms, a space for the veneration of craft and olivas’s ode to the meditative gaze as a regenerative force. The work also elicits questions about inheritance and how change is enacted in the critical processes of passing down and accepting inheritance: ancestral traditions of ceramics and altar making; la trokita blanca, a first-generation body like olivas himself; the buckets and shovels of our fathers’ and grandfathers’ livelihoods, given softness and transmuted into materials of formal excellence.

Experiencing these works, it’s impossible to forget the Kongo cultural scholar Fu Kiau Bunseki’s words to the late Robert Farris Thompson. When asked about the garden sculptures of stacked tires by Black southern folk artists, which Thompson encountered while conducting research in 1988, Bunseki stated: “The tire is a circle of an accomplished life. It is an nkata (circle, lap, symbol of competence) that holds the life of the plant, a symbol of the care that should be given to life in all its manifestations. It is really an encircling lap, like the crossed legs of a most important mother.”4

This encircling gesture of protection extends to the installation’s material reality outside the museum walls. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, olivas has dedicated much of his time to his work at the Crenshaw Dairy Mart (CDM), an abolitionist art hub in the city of Inglewood, in southwestern Los Angeles County. Cofounded in 2019 by olivas with the artists Patrisse Cullors and alexandre ali reza dorriz, CDM has offered dozens of public art projects, programs, in-person and digital exhibitions, and auctions of artworks by incarcerated artists in its efforts to combat injustices to its community that have been exacerbated by the global pandemic. The space also houses a suite of artist’s studios occupied by frequent collaborators, including Star Montana and Jake Freilich, the latter an organizer of the CDM’s popular free kids’ art kits, which were distributed during the summers of 2020 and 2021 in collaboration with the artist Lauren Halsey’s South Central–based food justice program, Summaeverythang. Most recently the artist-run collective established its abolitionist pod (prototype), an autonomous community garden and public sculpture, in collaboration with the Geffen Contemporary in Los Angeles (in 2021) and Chinatown’s Hilda L. Solis Care First Village (in 2022).

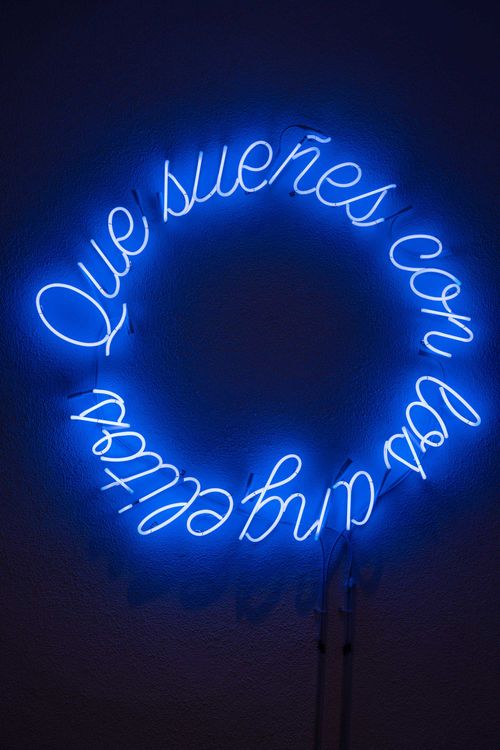

Taking his framework from CDM’s antiracist and anti-carceral philosophy, the artist also espouses a practice of healing through collaboration. Many of the works in the gallery were created with olivas’s creative partners Juan Carlos Morales, Andres Zavala, and Clay CA. A blue neon sculpture installed in the Hammer’s exterior courtyard , Que sueñes con los angelitos (2022), offers an incantation of its own, one olivas has returned to often in his work: May you dream with the angels. The Spanish phrase is a bedtime prayer for sweet dreams guided by angels, a protection spell for the dark hours without light. For olivas, it’s also an ode to Los Angeles, where “mentors, friends, and angels have guided him and nurtured his artistic practice” and where abolition can be visualized as an act of everyday creative collaboration.5

The toolshed, like an artist’s studio, serves as a kind of spirit house. Like any site that the poderes call home, it moves in its own time and demands veneration through dedicated stillness. Let’s Pray is an invitation to participate in this contemplation, a pact to create a better world and continuously unfolding future. In visualizing this politic through his aesthetic of the quotidian, olivas shows us that to find this language of liberation, we need only look to the land itself.

Notes

Epigraph: Quoted in Lydia Cabrera, El Monte (1959; Havana: Letras Cubanas, 1993), 136.

1. Noah Purifoy, One to One: Quarterly Report on Aspects of Creativity (January–March 1967), 1–2, Noah Purifoy Papers, 1935–1998, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

2. See Kellie Jones, “Interview: David Hammons,” Art Papers, July–August 1988, https://www.artpapers.org/interview-david-hammons/.

3. Angie Schmitt, “What We Can Learn from ‘Latino Urbanism,’” StreetsBlog, June 5, 2019, https://usa.streetsblog.org/2019/06/05/what-we-can-learn-from-latino-urbanism/.

4. Quoted in Robert Farris Thompson, “The Circle and the Branch: Renascent Kongo-American Art,” in Another Face in the Diamond: Pathways through the Black Atlantic South (New York: INTAR Hispanic Arts Center, 1988), 31.

5. Joseph Daniel Valencia, “noé olivas: Que sueñes con los angelitos,” 2019, https://roski.usc.edu/events/no%C3%A9-olivas%C2%A0que-sue%C3%B1es-con-los-angelitos.

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation. Lead funding is provided by the Hammer Collective. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy, with additional support from the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission.