Hammer Projects: Shadi Habib Allah

- – This is a past exhibition

Shadi Habib Allah began work on this project by engaging with corner stores in the Liberty City neighborhood of Miami, where a disproportionate percentage of the community is dependent on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, or “food stamps”). The artist was motivated by his interest in examining government welfare policies and their impact on a largely disenfranchised population. Habib Allah observed that these small, local stores maintain an interdependent relationship with customers by allowing them to buy groceries on credit and exchange food stamps for cash. Although these exchanges demonstrate a set of social relations organized around trust and accountability, they also embody the financial and racial inequity of programs such as SNAP. Welfare recipients typically enter into an unspoken social contract that dictates where they can live and what commodities they can access. As Habib Allah observes, these material facts become data points for widely held moral judgments about what makes a person a worthy welfare recipient.

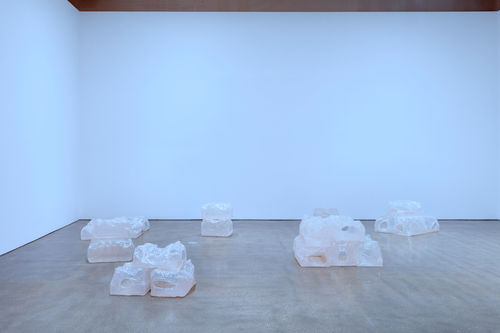

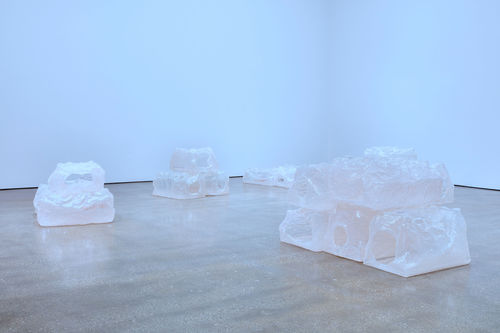

The discrepancy between the intent of welfare and the appearances or representations that it produces is at the conceptual center of Habib Allah’s installation. Measured Volumes (2018) is a series of sculptures that mimic the bulk packaging that encases bottled beverages, which would normally fill the shelves of a convenience store. Emptied of their contents, the silhouetted shapes are hollow representations of the otherwise familiar commodities. While the lack associated with scarcity lingers in these vacated replicas, their repetition and abundance in the exhibition also underscore a counter-narrative of plenitude.

Sound Appearance (2018) plays alongside the installation of sculptures. This audio work is comprised of snippets of commentary and dialogue from an episode of The Oprah Winfrey Show, titled “Welfare Debate.” The episode originally aired in 1986, during a period in which President Reagan’s conservative economic plan placed social welfare programs under heightened scrutiny. The opinions of the episode’s guests and audience members echo common sentiments of that era, when the US government was entrenched in a “war on poverty.” At the heart of the episode is a contentious discussion about whether the able-bodied are entitled to receive welfare and how beneficiaries of the state should look, behave, and perform. Habib Allah’s project argues that the debate about the disparities and dependencies wrought by social assistance programs remains open-ended and unresolved today.

Hammer Projects: Shadi Habib Allah is organized by Aram Moshayedi, curator, with Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, curatorial assistant.

Biography

Shadi Habib Allah (b. 1977, Jerusalem) currently lives and works in New York. His work has been the included in solo and group exhibitions at SculptureCenter, Long Island City, New York (2018); Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, Los Angeles (2017); Beursschouwburg, Brussels (2017); Portikus, Frankfurt (2016); National Gallery of Arts, Tirana, Albania (2014); Artist Space, New York (2013); Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2013); Tate Modern, London (2007); and Issaf Nashashibi Center, Jerusalem (2005), among others. Habib Allah has also participated in notable survey shows, including Sharjah Biennial 13, UAE (2017); New Museum Triennial, New York (2015); 53rd Venice Biennale (2009); and Riwaq Biennale, Ramallah, Palestine (2007). He was awarded the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Grant in 2011. Concurrent with the exhibition at the Hammer, Habib Allah will present a solo exhibition at the Renaissance Society, University of Chicago (2018); as well as a solo exhibition at CCA: Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow (2019), as part of The Consortium Commissions.

Essay

Shadi Habib Allah Interviewed by Aram Moshayedi

Shadi Habib Allah began work on this project by engaging with corner stores in the Liberty City neighborhood of Miami, where a disproportionate percentage of the community is dependent on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, or “food stamps”). The artist was motivated by his interest in examining government welfare policies and their impact on a largely disenfranchised population. Habib Allah observed that these small, local stores maintain an interdependent relationship with customers by allowing them to buy groceries on credit and exchange food stamps for cash. Although these exchanges demonstrate a set of social relations organized around trust and accountability, they also embody the financial and racial inequity of programs such as SNAP. Welfare recipients typically enter into an unspoken social contract that dictates where they can live and what commodities they can access. As Habib Allah observes, these material facts become data points for widely held moral judgments about what makes a person a worthy welfare recipient.

The discrepancy between the intent of welfare and the appearances or representations that it produces is at the conceptual center of Habib Allah’s installation. Measured Volumes(2018) is a series of sculptures that mimic the bulk packaging that encases bottled beverages, which would normally fill the shelves of a convenience store. Emptied of their contents, the silhouetted shapes are hollow representations of the otherwise familiar commodities. While the lack associated with scarcity lingers in these vacated replicas, their repetition and abundance in the exhibition also underscores a counter-narrative of plenitude.

Sound Appearance (2018) plays alongside the installation of sculptures. This audio work is comprised of snippets of commentary and dialogue from an episode of The Oprah Winfrey Show, titled “Welfare Debate.” The episode originally aired in 1986, during a period in which President Reagan’s conservative economic plan placed social welfare programs under heightened scrutiny. The opinions of the episode’s guests and audience members echo common sentiments of that era, when the US government was entrenched in a “war on poverty.” At the heart of the episode is a contentious discussion about whether the able-bodied are entitled to receive welfare and how beneficiaries of the state should look, behave, and perform. Habib Allah’s project argues that the debate about the disparities and dependencies wrought by social assistance programs remains open-ended and unresolved today.

Aram Moshayedi: Your new project began with a look into the distribution policies of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and has since evolved to address what you’ve characterized as an aesthetics of lack. You developed this project while you were living part-time in the Liberty City neighborhood of Miami. How did what you observed there shape your thinking about the project?

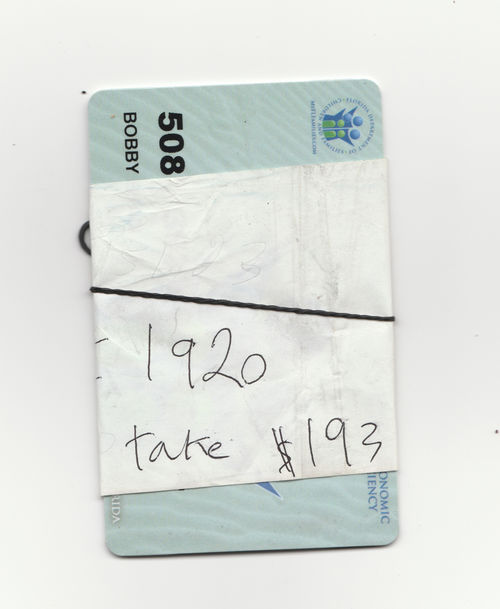

Shadi Habib Allah: It started by examining the distribution policies of social programs, but what shifted my focus was what I saw in the corner stores of Liberty City. Several years ago, they were stacked with groceries, but now they are almost empty. Despite that scarcity, the stores are still surviving. Their earnings have shifted away from groceries and food items to gambling, drug dealing, and food stamp exchanges (while that lasted). In the 1980s and 1990s, many stores exchanged food stamps for cash, when food stamps came as paper coupons. Since the digitization of the stamps, it has become more difficult to exchange them. The desolate look of the stores reflects a change in operations and the current sources of income.

AM: What initially drew you to Liberty City? Can you talk a bit about the specifics of this neighborhood within the context of Miami?

SHA: I used to hear people talk about it as being sketchy and notorious for crime. The corner stores were open 24/7 and booming then. They provided a social space for people from the neighborhood, almost like a meeting spot. The neighborhood has changed in recent years as a result of development, and the function of the corner stores has also changed. Yet change is almost endemic to Liberty City. The area began as a federally funded development to relocate African Americans from Overtown, a segregated community in downtown Miami. Around five miles north of Overtown, Liberty Square was built from 1934 to 1937, during the New Deal era, by the Miami Housing Authority. Redevelopment of the housing development has now begun.

AM: The Oprah Winfrey Show episode that you sourced for the sound installation originally aired in 1986. It has since been referenced in a number of texts and critical essays that look at poverty and welfare distribution policies in the United States. It’s apparent that the “welfare debate” was a hot-button issue at the height of Reaganomics. Based on your recent research and observations, how does this issue resonate in the current economic climate?

SHA: My attention shifted to a more general look at the aesthetics of impoverishment when I came across the archived Oprah episode during my research. This particular episode revealed a consensus, in the 1980s, about a specific “look” that is expected of those who qualify for welfare. I was led to the Oprah episode by an article by David Ellwood, a professor of political economy and an economic advisor during the presidency of Bill Clinton. Supposedly, much of the welfare program as it exists today was inherited from the plan Ellwood developed under Clinton. When Clinton was elected, he tried to push for welfare reform. Ellwood’s plan called for training programs, guaranteed jobs, child support, and even last-resort government jobs for beneficiaries, after ending their welfare support. But the Republicans, who held the majority in Congress, blocked implementation of most of Ellwood’s ideas. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, which was passed in 1996, stripped his plan of its defining qualities. The act was criticized for measuring success, in part, through a decrease in the number of recipients in the welfare system. The mothers that were phased out of welfare after two years often entered into jobs that didn’t pay well, which ultimately led to concomitant increases in homelessness. Welfare is always the target of budget cuts. The current administration signed an executive order [Executive Order Reducing Poverty in America by Promoting Opportunity and Economic Mobility] that called for stronger requirements for welfare; this move effectively reversed an Obama administration policy that relaxed the work requirements of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. More requirements of welfare recipients means less government spending. With this recent executive order, states now have the right to choose how to spend the money. They can put families on work programs, or they can simply turn them away.

AM: In the Oprah episode, Lawrence Mead appeared as a guest panelist. In Mead’s book, Beyond Entitlement: The Social Obligations of Citizenship, which was published the same year the episode aired, he questioned the status of so-called able-bodied welfare recipients. I was taken by the manner in which certain audience members echoed Mead’s ideas. Do you see a larger set of questions at stake in this debate that have to do with class?

SHA: It was interesting to see how low-income people on the episode attacked welfare recipients. You might expect it from a wealthier class, those who are distanced from the experience and conditions of poverty. But I think antagonisms are more vocal and racism is more outspoken when people use them to separate themselves from their own social class. This was also apparent in the interactions between co-workers in my video The King and the Jester (2010), which I filmed at Perfect Auto Paint & Body Shop in Miami.

AM: The so-called legal status of certain individuals or sub-groups seems to inform your work. How would you characterize that relationship within this most recent project?

SHA: I think it’s more about the appearance of being in accordance with the law and how certain attitudes can become vehicles for legal navigation. At the same time, these attitudes return to questions about what is legal and what’s acceptable. Subjects in my work try to replicate certain attitudes of acceptability.

AM: Can you give an example of what you mean by “acceptability”?

SHA: Acceptability in this sense refers to a beneficiary having to display impoverishment in order to qualify to receive benefits, like the woman in the Oprah episode who refers to having her children looking nasty when visiting the Department of Public Aid. Even if she’s not telling the truth, there’s some reality in the need to be acceptably pitiable in order to receive a service or a treatment.

AM: For the audio installation at the Hammer, why have you decided to isolate the audio from this episode and deny its visual representation? How does the audio work relate to the sculptures that are also at the center of this project?

SHA: Spoken words have a tendency to be more immediate than visuals. I also wanted to use the audio without the visuals to keep the work ambiguous and open ended, as if to ask in what context can these conversations take place. I chose sound for this project because I wanted to focus on the qualifying appearance. It’s not about what the beneficiaries have or how much the corner store sells but what is seen, or what appears to be legitimate. It’s about scarcity. Within the installation at the Hammer, there is a notable difference between the sound and the sculptures. The sculptures are about the value of necessity or, rather, poverty, and whether appearance informs this valuation. The audio drawn from the Oprah episode addresses the appearance of people in need.

AM: Can you talk about the ways in which the sound installation employs the voices of audience members to make certain claims about the enduring connections between race and class in the US context? Were you thinking about this when you were developing the piece?

SHA: I wouldn’t say that I thought about that from the beginning. But what stands out in the episode is the voice of the audience, although it seems that Mead and Winfrey set a certain attitude or tone for the conversation. For example, in the video, you can see an approving smile on Mead’s face when an audience member bashes a beneficiary. Winfrey and Mead and the two other guests—former California State Senator Diane Watson and Felicia Dodson, a welfare recipient—are meant to have weight on the show. But the audience appears to disregard Watson’s opinion, and the beneficiary is repeatedly attacked as someone who feels entitled, who refuses to settle for the minimum wage and start at the bottom of the economic ladder. The episode frames the discussion from the beginning with a question about how the public feels about able-bodied welfare recipients “sitting home with their feet up.” This reflects American politics and how many people living in poverty seem to think that the system is not the primary problem. Rather, they blame the problem on a certain class or race. Specifically, I focused on the words of the audience that describe appearances. When you hear one caller attack the beneficiary guest about her dress, it may seem that she is wearing an extravagant dress. But, in reality, the dress doesn’t look fancy. It just looks clean.

AM: In past works, you have attempted to immerse yourself within particular economic systems as a way of better understanding their inner workings. How has the process differed for this new project?

SHA: Most of my past works have relied on types of research that involve text or written documents in addition to embedding myself in some kind of context. In general, I’m reluctant to make the research an evident part of the work. I try to keep it separate, just as a background for myself. In this project, the research material has become more present, and the Oprah episode is the work’s anchor, signaling the political debate around welfare. But I try to synthesize the source material by looking at it from a specific point of view. In this case, the qualifying appearance for legitimacy is the framework. One of my earlier works, Marat’s Bathtub (2013), relied solely on reading material. The project for the Hammer borrows from both research and immersion.

AM: In the process of working on this exhibition, you have gathered a fair amount of background information from what might be considered “unofficial” sources. Can you discuss the status of this material and how it competes with a notion of official data, which discussions such as these typically rely upon?

SHA: I would respond to this by asking another question. Does this material and its status exist as a response to the official material, or is it a progression from a set of mechanisms that emerged from my digression and intervention as an artist working at a distance from the official data? I think it’s interesting to see how these forms of data represent competing ways of dealing with an issue. The official one has a stronger presence; the unofficial one has to stay hidden, otherwise the official data loses its status or strength.

AM: Do you mean that you’re contributing something that can be read alongside the official data that claims to accurately represent and speak on behalf of a disenfranchised community?

SHA: My work is not about the representation of specific communities or locales. Rather, it tries to show how underserved and underrepresented communities navigate visibility in a system that dictates what is legal or illegal, legitimate or illegitimate.

Hammer Projects: Shadi Habib Allah is part of The Consortium Commissions – a project initiated by Mophradat. It is presented in association with CCA: Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow and in conjunction with a related solo exhibition at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, September 15–November 4, 2018.

The Hammer Projects series is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

The Hammer Projects series is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy, with additional support from Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley and the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission.