Hammer Projects: Molly Lowe

- – This is a past exhibition

In her newest body of work, Molly Lowe considers the ways in which our image saturated culture is changing our sense of reality and ourselves.

New York–based artist Molly Lowe addresses the ways in which technology has changed how we experience “reality,” relate to other people, and understand our own bodies and identities. In this new body of work, comprised of a series of painted portraits and a large sculptural installation, Lowe considers how the proliferation of images of people we’ve all grown accustomed to seeing on a daily basis on television, social media, and the internet makes us feel simultaneously more connected and more isolated than ever before. Her cast of characters are familiar and yet completely unknowable—trapped in a kind of existential limbo, divorced from reality but still stuck within its inescapable confines. Lowe is skeptical of our hyper-voyeuristic culture, and her work implores us to pause and consider what we really gain from the intimate and often anonymous exchanges technology affords.

Hammer Projects: Molly Lowe is organized by MacKenzie Stevens, curatorial associate.

Biography

Molly Lowe (b. 1983, Palo Alto, California) lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Lowe received her BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2005 and her MFA from Columbia University in 2012. She has had exhibitions and performances at Pioneer Works, Brooklyn (2016); Suzanne Geiss Company, New York (2014); SculptureCenter, Long Island City, New York (2013); and Performa 13, New York (2013). Her films have screened at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (2017) and JOAN, Los Angeles (2016). Lowe has participated in residencies at the Shandaken Project, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York (2015); Pioneer Works, Brooklyn (2015); Recess Art, New York (2013); and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Maine (2008). In 2015, she received the New York Foundation for the Arts interdisciplinary artist fellowship award, and she was recently nominated for a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation award.

Essay

"L’enfer, c’est les autres" (Hell is just – other people)

—Jean Paul Sartre, No Exit, 1944

Written during World War II, No Exit is a meditation on the narcissistic and self-loathing tendencies Jean-Paul Sartre identified as particularly characteristic of human nature. It is the story of three people confined to a stodgy period room in hell, where their torture is neither fire nor brimstone but simply being trapped in the company of the others. Sartre was responding to a moment of total despair, an existential crisis and lack of faith in humanity caused by decades of war, destruction, and genocide in Europe. Today, many of us are again facing a form of existential crisis, fueled by political, racial, and religious divisions and global conflicts, causing us to question one another, our communities, and even ourselves.

Molly Lowe’s recent work reckons with the uncertain times we find ourselves living in; the exhaustion and anxiety many of us feel from the constant stream of troubling, even terrifying news; our feelings of isolation and disconnectedness despite the array of new technologies that are meant to bring us closer across geographic divides. Lowe contends with the ways in which the proliferation of information and images we have access to may not be uniting us, but rather the opposite. Have we become hyper-judgmental voyeurs in constant pursuit of the next tantalizing spectacle? Lowe addresses this question in two distinct but connected works: a sculptural installation, and a series of painted portraits culled from imagery sourced online.

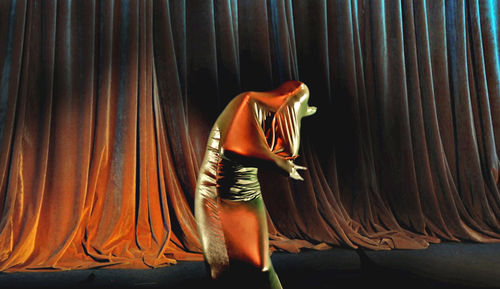

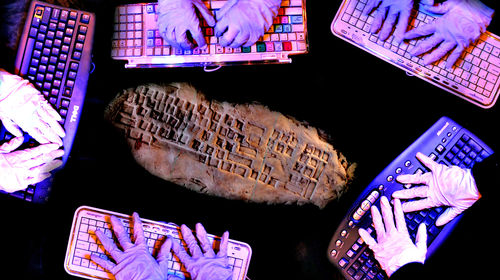

The body, in some form, is frequently the subject of Lowe’s sculptures, installations, videos, and, more recently, paintings. Her representations of the body are almost always partial, consisting of limbs, hands, or digits, directing us to the ways in which technology has altered how we use our bodies, and by extension, how we perceive ourselves. In Formed, a short video from 2013, she reduces the human body to hands and fingers—that is, the tools necessary to make art, click a keyboard, or swipe a touchscreen. Formed is a quasi-self-portrait, as Lowe’s hands are those that form, mold, sculpt, click, and swipe in its short, dreamlike vignettes. Sorry. Excuse Me. Thank You is a site-specific installation originally made for Suzanne Geiss Company in 2014, and is a humorous and macabre take on how riding mass transit can be a surreal experience, where bodies become body parts and “sorry, excuse me, thank you” is a constant refrain. Lowe’s stuffed soft sculptures turn the human body into something grotesque and even abject, reducing people to pieces of meat hung in a meat locker. In Powers of Horror (1980), the philosopher Julia Kristeva argued that the abject body—distorted, partial, leaking or excreting fluids—signifies a loss of control or propriety, and thus is transgressive.1 Sorry. Excuse Me. Thank You challenges notions of propriety in this manner, as the bodies on display are dismembered and bare, rejecting normative rules of etiquette.

On Your Mark (2017), the focal point of Lowe’s Hammer Project, also comments on the ways in which human behavior shifts when we are in close proximity. Here, however, there is absolutely no sense of propriety, no underlying arrangement or organizing principle. Rather, the flesh-colored blobs that fill the interior of the misshapen foosball table are completely entangled, almost as if they are suspended in the moment of trampling one other in an effort to get free. The mirrored walls of the table’s interior only intensify the macabre scene by creating the illusion of a never-ending and inescapable expanse of entrapment. Lowe’s version of hell is not confinement in a room with people who bring out your worst, as Sartre surmised, but being stuck in a crowd.

On Your Mark conjures images of protests, riots, and mass shootings of the last several decades while also commenting on narcissism. As Lowe recently put it, the figures in the work “are frozen under the spell of their own reflection. It’s a hellish scene, where people appear restless and powerless, drowning in orgiastic vanity.”2 As we observe ugly or terrifying scenarios in cities around the world on our screens, we are removed from the chaos and violence and yet totally immersed in it. On Your Mark compels us to consider how we are emotionally affected when we watch or read about such events, but also how technology can make these incidents seem abstract, fleeting, and perhaps even surreal or dreamlike. On Your Mark is also a metaphor writ large—we, too, often feel trapped in our present circumstances, confined to a voyeuristic echo chamber, when our voices go unheard or fail to effect significant traction or change.

What began as an effort to distract herself from the daily news soon developed into a regular exercise that allowed Lowe to get lost in the lives of other people, not in the “real” world, but on the internet.3 The people she encountered through her online research were intriguing, and the “types” she found herself most drawn to expressed the antithetical characteristics of contemporary culture: anxious but self-assured, damaged and also strong. Portrait Series 2017 (2017), also included in Lowe’s installation at the Hammer, consists of paintings on paper whose subject matter ranges from tantalizing, exquisitely rendered portrayals of anonymous people to hazy scenes of darkness or absurd humor. Installed together in a strip around the gallery, the paintings remind us of the wild assortment of images we might encounter while browsing the internet: a group of mimes doing a keg stand, a baby who has plunged her face into a cake, a woman in a hijab who has momentarily transformed herself with a Snapchat filter into a panda bear, adhering to tradition while embracing youth culture. In yet another, a man wearing a bandanna and a tie-dyed T-shirt holds a rifle; is he a gun-toting hippie or a backwoods survivalist? Ambiguity is a defining feature of the series, and some works are completely indecipherable.

New technologies enable us to study other people from afar, to devour news, and to get lost in images, from cute babies to shootings to sexy selfies. Our desire to look is intrinsic—we are visual creatures—and yet the mindless looking and searching that technology affords is problematic, as it distracts and disconnects us from the “real” world. On Your Mark reckons with this, pointing to the ways in which layers of mediation can transform an individualized human being into something much more abstract. And yet, by invoking the massacres we’ve witnessed from afar, it allows us to project features onto the amorphous blobs, momentarily transforming them from flesh-toned lumps into people. Lowe’s portraits also do this work, and in this way, Portrait Series 2017 implores us to mull over this assembled cast of characters and remember that they are paintings of “real” people, not just orphaned image flotsam floating around on the internet. Together, these works offer up a slice of contemporary culture, narrowing in on the quirky and the commonplace, the clichéd and the atypical, the definitive and the unknown.

—MacKenzie Stevens

Notes

1. Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia

University Press, 1982). Originally published as Pouvoirs de l’horreur (Paris:

Editions du Seuil, 1980).

2. Email from the artist, January 2, 2018.

3. Email from the artist, December 10, 2017.

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.