Hammer Projects: Lawrence Abu Hamdan

- – This is a past exhibition

In 2016, artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan began an acoustic investigation into Sayndaya, a Syrian military prison north of Damascus. Given that the prison has remained inaccessible to independent monitors and observers and that most detainees are kept in total darkness, Abu Hamdan designed “ear witness” interviews to reconstruct the conditions of the prison and its architectural plans through the acoustic memories of surviving former detainees. These interviews formed a central component of a report on the prison for Amnesty International and the independent research group Forensic Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London. Based on the findings of the report, Abu Hamdan initiated a body of work that experiments with the means by which crimes at the threshold of perception can become documented. For this exhibition, Abu Hamdan will present the first two works in this ongoing project. The project’s two parts respectively utilize techniques of measuring silence and mapping acoustic leakage, showing the ways in which sound becomes sight and sight becomes sound—the results of communication and perception being violently forced to the limits of both sensory fields.

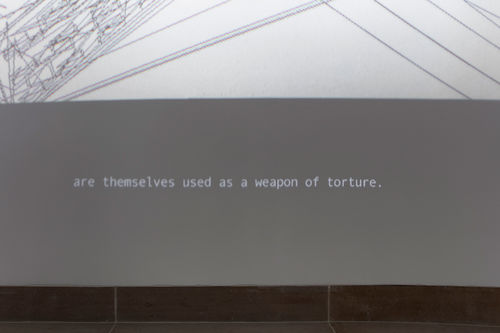

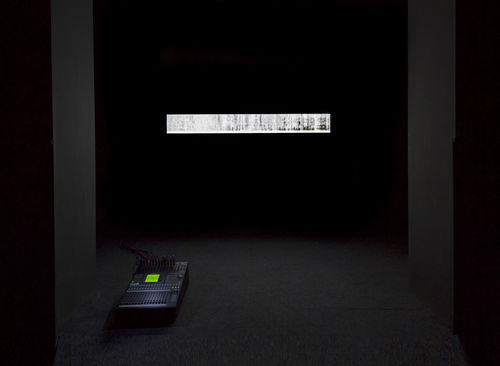

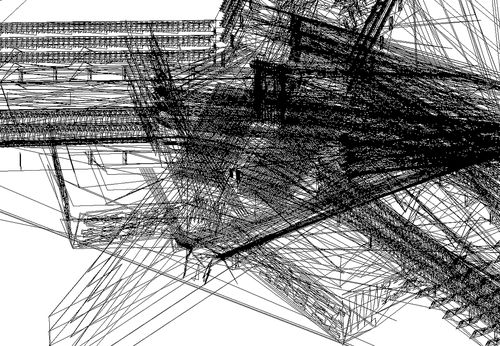

With Saydnaya (the missing 19db) and Saydnaya (ray traces) (both 2017), Abu Hamdan approximates the ways in which the architectural, acoustic, and psychological conditions of the Syrian prison become intertwined. Saydnaya (the missing 19db) is an audio essay installed at the entrance of the gallery that emphasizes a notable decrease in the volume at which detainees could whisper to one another after the protests began in 2011. The work speculates that the 19- decibel drop is a testament—amidst a lack of material evidence—to the transformation of Saydnaya from a prison to a death camp. Saydnaya (ray traces), by comparison, envisions a reconstruction of the prison based on the acoustic memories that have been imprinted onto those who were once held there. Overhead projectors cast images that have been rendered through ray tracing, a digital visualization tool used in architectural design to map the leakages of sound throughout a given structure. The basis of both works is an attempt to understand the manner in which sound becomes sight and sight becomes sound—as a result of communication and perception being forced to the limits of both sensory fields. In examining the specific ways in which sound in Saydnaya has been experienced by those confined there—encoded into their memories and felt as a weapon—we are compelled to expand the ways in which we listen to and are able to hear war crimes.

Hammer Projects: Lawrence Abu Hamdan is organized by Aram Moshayedi, curator, with Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, curatorial assistant.

Biography

Lawrence Abu Hamdan (b. 1985, Amman, Jordan) currently lives and works in Beirut, Lebanon and Berlin. He has had solo exhibitions at Portikus, Frankfurt (2016); Kunsthalle St. Gallen, Switzerland (2015); Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Netherlands (2014); and The Showroom, London (2012). Abu Hamdan participated in the Sharjah Biennial 13, UAE (2017); Liverpool Biennial (2016); 11th Gwangju Biennale, South Korea (2016); and New Museum Triennial, New York (2012). Other notable group exhibitions have taken place at Moderna Museet, Stockholm (2017); Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (2017); Museum Folkwang Essen, Germany (2016); Whitechapel Gallery, London (2016); Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (2014); Beirut Art Center, Beirut, Lebanon (2014); and Institute of Contemporary Arts, London (2012); among others. Abu Hamdan was awarded the Abraaj Group Art Prize in 2018 and the International Nam June Paik Award in 2016.

Essay

By Aram Moshayedi

Salam Othman, a former detainee of the notorious Syrian prison Saydnaya, located fifteen miles north of Damascus, recalls the cell where he was once imprisoned: “We know the cell tile by tile, so well that we can walk in it even in the dark.” His testimony is part of a report initiated in 2016 by Amnesty International. The team of researchers included artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan, who worked with the independent research group Forensic Architecture, based at Goldsmiths, University of London. Abu Hamdan’s contribution to the Amnesty International report took the form of earwitness testimonies. Recollections such as Othman’s aided in the researchers’ attempts to reconstruct the architectural and psychological conditions of the prison, which has remained inaccessible to outside monitors and thus defies conventional representation.

Abu Hamdan poses a series of self-reflexive questions that address the role of a research-based practice within a broader discursive field. Though attempting to understand the human rights violations at Saydnaya initiated this pursuit, Abu Hamdan’s two artworks that have thus far emerged from his research speak more broadly about an aesthetics of evidence and an evidence of aesthetics. Together, these aesthetic documents use the formal properties of sound, text, and image to represent an experience of trauma and violence beyond literal reconstruction.

Saydnaya (ray traces) envisions a reconstruction of the prison via overhead projectors that cast images that have been rendered through ray tracing, a digital visualization tool used in architectural design to map the leakages of sound throughout a given structure. In the audio essay Saydnaya (the missing 19db), testimonies, voiceover, cacophonous whispers, extreme silence, and test tones comingle to suggest the ways in which acoustic memories are retained in the physical body as trauma. The installation’s audio emphasizes and manipulates qualities of voice, proximity to sound, acoustic depths, and a dislocation of the senses as ways of approximating the conditions of the prison—an environment otherwise designed to restrict perception. Saydnaya (the missing 19db) documents a nineteen-decibel drop in sound within the prison that is mapped onto the acoustic memories of those detainees who were there after 2011. Amnesty cites this significant shift as evidence of its transformation into a torture prison at that time. As an artwork, Saydnaya (the missing 19db) transforms research into a multisensory experience. Its final form is itself a document of perceptions, a recognition of testimony as a material that contains experiences that evade documentation as such. In this context, speech shifts from a communicative device into an object with unique characteristics.

Collectively, Abu Hamdan’s works address the politics of sound and listening in a cultural climate—legal, political, artistic—that is otherwise dominated by vision and visuality. Earlier works include investigations of a specific incident involving the death of two Palestinian teenagers by Israeli soldiers in the occupied West Bank (Rubber Coated Steel, 2016); the vibrations felt by objects (A Convention of Tiny Movements, 2015); the political and religious implications of noise-abatement policies in Cairo (The All-Hearing, 2014); and the controversial use of voice analysis to determine the authenticity of asylum seekers’ accents in the United Kingdom (The Freedom of Speech Itself, 2012). Abu Hamdan’s propositions are at times speculative, but they are grounded in a personal and political conviction that is sensitive to the testimonials, interviews, and accounts that contribute to the larger body of research focused on sound and acoustic space.

Abu Hamdan’s research-based work takes part in an art historical lineage—including Conceptual art and institutional critique—that places value on artistic methodologies in the pursuit of truths, whether speculative or analytical, theoretical or practical. In the Lebanese context, where Abu Hamdan currently lives and works, artists such as Walid Raad sit squarely in this trajectory, though to different ends. Raad is known for having formed the fictional research project The Atlas Group (1989–2004) to analyze the aftereffects of the Lebanese Civil War and its relationship to the contemporary history of Lebanon. Artists such as Hito Steyerl and Trevor Paglen are also considered to have research-based leanings, but the more this term is used as a shorthand, the more porous its definition becomes. Research, it could be argued, is at the basis of most artistic work; however, the ways in which research is emphasized and presented separate Abu Hamdan from others. The late Mike Kelley is an artist seldom associated with research as it’s understood today. But his Educational Complex (1995), which attempts to depict, as reconstructed from memory, every school that the artist attended, could perhaps offer some insight into the ways in which Abu Hamdan translates Saydnaya as a specific architecture through the memories of those who have experienced its horrors firsthand, and how the spottiness of their memories contributes to, rather than undermines, an overall understanding of the place.

As much as the prison has preoccupied Abu Hamdan’s research, the immaterial traces that have seeped beyond its architecture are what characterize both works of contemporary art. The basis of Saydnaya (ray traces) and Saydnaya (the missing 19db) is an attempt to understand the manner in which sound becomes sight and sight becomes sound—the results of communication and perception being forced to the limits of both sensory fields. With regard to the prison, Abu Hamdan has focused specifically on the perception of what was heard by detainees such as Jamal Abdou, who recollected of the darkness: “You try to build an image based on the sounds you hear.” For Abu Hamdan, the hypersensitivity to sound and an ability to construct images in the absence of what is seen defines his work and our encounter with the sounds and images he conjures forth as evidence of a practice, as evidence of research, and as evidence of his (and our) proximity to the crimes at Saydnaya through the individuals who have absorbed them into their being.

Note

1. Amnesty International and Forensic Architecture, “Saydnaya: Inside a Syrian Torture Prison,” https://saydnaya.amnesty.org/.

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.