Hammer Projects: Tabaimo

- – This is a past exhibition

Japanese artist Tabaimo creates a site-specific work for the Hammer lobby wall for her first solo exhibition in Los Angeles.

The artist Tabaimo (b. 1975, Nagano, Japan) depicts what might exist beneath calm surfaces—her active imagination proposes a fantastic world full of activity that challenges our understanding of reality. Whether roaming through the activities of a bathhouse, diving into the contents of a purse, watching a housewife make dinner, or making greenery bloom from beneath a figure’s skin, the artist gives surreal life to banal occurrences, often incorporating into these contemporary tableaux allegorical imagery from Japanese art traditions like woodcuts. For the Hammer Museum’s lobby wall, Tabaimo premieres a new installation that incorporates large-scale drawings and video.

Hammer Projects: Tabaimo is organized by Emily Gonzalez-Jarrett, curatorial associate.

Essay

By Emily Gonzalez-Jarrett

Born in 1975, Tabaimo is part of Japan’s “lost generation,” who in their youth witnessed the decline following the country’s technological boom. A recession in the 1990s dealt a devastating blow to the nation that had rebounded so strongly after World War II, due in large part to its strong collective ethos and tendency toward precision. The economy slowly recovered over the following decade, but was affected by the 2008 worldwide crash and has had slow growth since due to an aging workforce and declining birth rates. Japan has advanced industries and its products are highly valued abroad, but this has made exports increasingly important, and the international market can be precarious

Out of this environment of boom and bust, like many of her peers, Tabaimo has confronted the pressures of modernization and the influence of the West, and on a more personal level has come to terms with her own limitations as an individual. She thought as a child that she was special—smarter and more talented than other children. As she grew up, she took her natural talents for granted and so fell behind in her grades, sports, and drawing. Through this she realized her own ordinariness—that she was no more gifted than others, and that progress requires effort.

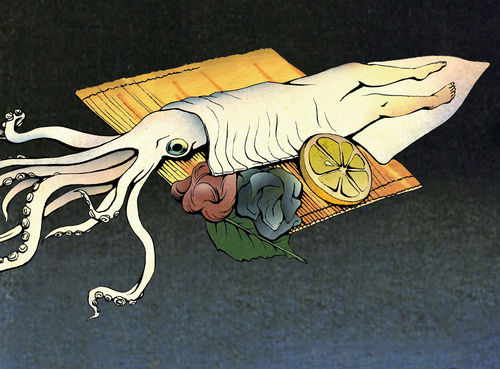

In contrast to artists like Takashi Murakami and Mariko Mori, who came to prominence a generation before her and highlighted otaku subculture, Tabaimo explores the depths that exist in the seemingly unremarkable. Through video, drawing, and installation, she depicts what lies beneath calm surfaces—her active imagination proposes a fantastic world full of activity that challenges our understanding of reality. Whether watching a housewife make dinner, peeking into a women’s public restroom, or making greenery bloom from a severed body part, the artist gives surreal life to otherwise banal scenarios, often incorporating into her tableaux allegorical imagery from Japanese art traditions like the woodcut.

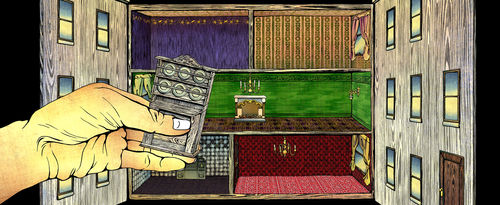

Despite their humor and playfulness, her drawings and animations are also imbued with a sense of tension and precariousness. In at the bottom (2007), the viewer stands on top of a platform and looks down at insects shedding their wings in a vortex. Standing in front of danDAN (2009), a video projected onto a three-sided panel on the wall, the viewer has the disorienting feeling of looking into a house from above. This motif was evident in the artist’s very first video installation, Nippon no Daidokoro (Japanese Kitchen, 1999), which begins with a weatherperson’s forecast of sun with showers of high school students and scattered junior high school students in the afternoon. As a housewife cooks dinner, a pair of teenage legs is shown on a building ledge. Headlines from the evening news appear in between scenes, and the legs fall through the sky while the housewife continues to cook. Among her produce and cabinets, miniature people appear as ingredients for her meal: she considers a Buddhist monk in a pickle jar, she microwaves a politician, and even her husband is there working at his desk in the refrigerator. A news headline announces that he has lost his job due to a bad economy, and she chops off his head for dinner. Next, a headless husband comes home with a gun, following which the wife is shown face down on the kitchen floor as the pots and pans boil over. The piece is compelling for its simultaneous absurdity, humor, and violence.

In the video installation Public conVENience (2006), Tabaimo peers into public and private spaces within a public restroom. She considers behaviors in this space as analogous to those on the Internet: the restroom is open to all, but has particular areas where no one sees what others are doing.1 The viewer follows women in and out of the stalls as they flush away secrets and wash away evidence of violence. Our total consumption by the Internet is an ongoing concern for the artist, and it comes up again in the recent performance outer-net (2017), where a set designed by Tabaimo encloses and excludes the musicians and dancers. Doves and inanimate objects fly around the interior while a bubble inside a birdcage stretches beyond the bars, but cannot squeeze its way out. This all speaks to a parsing of reality and fantasy, and exterior and interior spaces. Tabaimo frequently touches on individuals grappling with how much they will allow the Internet and technology into their lives. She foresees a time when the physical and digital worlds will coexist harmoniously, but knows that it is still a struggle at this time.

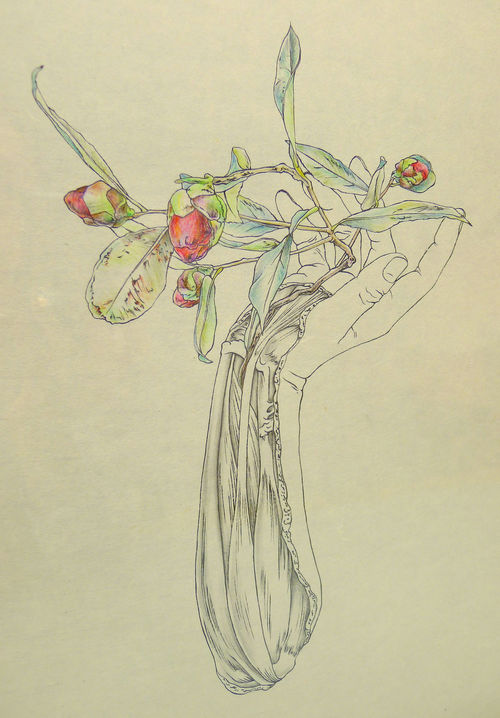

Promoting coexistence and respect, ikebana, the Japanese tradition of flower arranging, aims to bridge humanity and nature. Inspired in part by her mother’s ikebana practice, Tabaimo began illustrating dismembered body parts in a series entitled flow-wer (2014–15), which is the basis for her new installation at the Hammer Museum. The artist hopes that viewers will contemplate the possibilities of the body by looking at a separated part of one, as one would a flower in a vase, which is also cut from something larger. What conditions shaped this body? What would have continued had the body remained intact? What can the limb mean now that it is on its own? She is careful to stress that, as in ikebana, none of these possibilities are bad. They simply are worthy of consideration.

In discussing this series, Tabaimo uses the Japanese word jitto, which describes the quality of firmly standing still, unmovable. Tabaimo understands this term to also mean continued movement in spite of restrictive conditions.2 By picking just a part of the body, the artist opens up a new space for possibility. In the new drawings rendered on a monumental scale along the Hammer’s lobby wall, limbs, organs, and bones are exposed as in a medical textbook. But instead of the usual, anatomically correct imagery involving muscles, veins, and sinews, plants sprout from within. The body parts are depicted in black ink with some shading, but the blossoming vegetation is brightly executed with wax crayons. It seems to suggests potential for new growth, new ways to move in the world. Tabaimo’s work pushes against the rigidity of societal norms, creating a space that is open-ended and generative.

During Japan’s Tokugawa period (1603–1867), power was held by the shoguns, who created a four-class hierarchy with warriors at the top, followed by farmers, then artisans, and merchants at the bottom. In this worldview, merchants had the least to offer of the professions because they did not create anything but only exchanged goods, which was not necessary to survival like protection, nutrition, or tools. As (visual and performing) artists sold their work to the wealthy, they straddled the line between artisans and merchants. Artists lived alongside the pleasure districts of Tokyo, which was known as the Floating World. It was a place of decadence and indulgence, but also subversion. Openly satirical images of the power system were widely available due to the easy reproducibility of the woodcut print, and generally tolerated by the authorities, as artists were viewed as the lowest caste of society, and therefore powerless.

Still, these prints served as a critical outlet against the rigidity of the rulers. Today, the Floating World has come to mean a mindset wherein one lives for the moment, since Buddhist philosophy holds that this world is transitory. In a similar vein, contemporary artist Tabaimo uses her own surreal motifs to look deeper into modern Japan and question what underlies the quiet discipline projected by the culture. Whether depicting a household drama, our inner lives, or the possibilities of the body, Tabaimo’s work always reveals something unexpected about the private lives of others.

Notes

1. Artist interview on Art21, April 21, 2012.

2. Tabaimo, Jitto (Basel: Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie, 2016).

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.

Hammer Projects: Tabaimo received in-kind support from NEC Display Solutions of America.