Hammer Projects: Simon Denny

- – This is a past exhibition

Considering the economic and social implications of recent information technologies, the Berlin-based artist Simon Denny (b. 1982, Auckland, New Zealand) undertakes research-based projects that offer critical insight into the conditions of exchange and the production of knowledge in the digital world. Rendering the immaterial flow of information into visible and tangible objects, Denny’s sculptural installations often approximate the visual language, style, and forms that are integral to the Internet and the culture that surrounds it.

Denny’s current research centers on the blockchain, a protocol for an online database that can record and execute contracts, financial transactions, property ownership transfers, elections, and much more. As the underlying structure of the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, the blockchain has the potential to revolutionize any transaction that would otherwise require third-party oversight. The real companies presented in this installation—Digital Asset, 21, and Ethereum—offer three distinct perspectives on the possibilities of the blockchain and its associated market ambitions. Denny’s sculptures are modeled after typical trade fair booths to convey the tenor and ethos of each company. Accompanying postage stamp designs and adapted versions of the board game Risk speculate on the intertwined nature of blockchain technology and the formation of supranational economic models.

The proposed financial applications of blockchain technology range from increased efficiency in banking practices to the creation of decentralized, peer-to-peer networks for commerce. Companies such as Ethereum are developing ways to radically alter not just monetary systems, but organizational practices of all kinds. The three companies that form the basis of Denny’s research are for better or worse determining the shape and future of transaction-based economies. As such, Denny has taken on the task of mediating the look, meaning, and implications of possible new world orders.

Hammer Projects: Simon Denny is organized by curator Aram Moshayedi with Emily Gonzalez-Jarrett, curatorial associate.

Biography

Simon Denny (b. 1982, Auckland, New Zealand) is currently based in Berlin, where he has lived since studying at the Städelschule, Frankfurt in 2009. Recent solo exhibitions of his work have taken place at WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels (2016); Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London (2015); MoMA PS1, New York (2015); Portikus, Frankfurt (2014); Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna (2013); Kunstverein Munich, Munich (2013), Aspen Art Museum, Aspen (2012); NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein, Aachen, Germany (2011); Contemporary Art Museum, Saint Louis (2010), as well the 56th Venice Biennale, where he represented New Zealand (2015). He has been included in group exhibitions at Kunstverein in Hamburg, Germany (2016); Kunsthalle Wein, Vienna (2015); Kunsthalle St. Gallen, Switzerland (2014); Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing (2014); Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof, Museum für Gegenwert, Berlin (2013); Centre Pompidou, Paris (2013); Institute of Contemporary Arts, London (2012); Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2011); and Musée d’Art Contemporain de Bordeaux (2011) as well as the 9th Berlin Biennale (2016).

Essay

By Emily Gonzalez-Jarrett

Imagine a world where trust is guaranteed, a world without borders, a world in which each and every one of us takes part in the whole. This world is already here, embedded in the blockchain, waiting for its emergence.1

Like many of his generation, Simon Denny has matured alongside rapidly evolving technologies that have radically changed the fundamental practices of daily life. As an artist he adapts to new technologies and attempts to understand these changes, even as he sees the prospect of an overloaded technological dystopia. Through collaborations with professionals from brand development, graphic design, and commercial production, Denny’s work in video, sculpture, and installation synthesizes recent developments in technology and media with the applied nature of visual art. The resulting projects are deceptively close to their real-world models and as such blur the line between art and promotional material.

Like the artist Fred Wilson, an early practitioner of institutional critique who uses the conventions of the museum to subvert it, Denny uses the tools of the tech trade to question technology’s promise of progress. In 1992, Wilson created his seminal work Mining the Museum by displaying “hidden” objects from the Maryland Historical Society’s collection such as Ku Klux Klan masks and slavery reward posters alongside the usual fare like antique baby carriages and hunting guns, thereby pointing to the difficult history of the organization and the country. Instead of the museum, Denny takes on the intersection of the banking industry and technology. His current research centers on the blockchain, a protocol for an online database that can record and execute contracts, financial transactions, property ownership transfers, elections, and much more. As the underlying structure of the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, the blockchain has the potential to revolutionize any transaction that would otherwise require third-party oversight. Focusing on real-world companies as case studies, Denny presents three possible directions for the emerging industry.

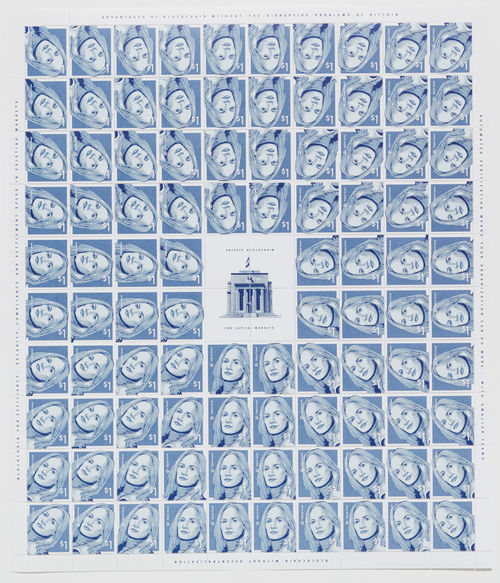

Digital Asset has the most conservative business model of these three companies betting on the future of the blockchain. Based in New York and helmed by Blythe Masters, a former J. P. Morgan executive who developed the modern credit default swap, the company creates proprietary blockchains to record and protect financial transactions. Digital Asset is interested in blockchains as impervious, ever-evolving ledgers that are processed, stored, and authenticated by computers. Instead of relying on individuals to enter and verify transactions, which takes time and is susceptible to human error, Digital Asset offers banks a technological alternative. Their product increases efficiency and security for institutions dealing in finance and capital.

21 is a Silicon Valley–based startup, led by Balaji Srinivasan, that envisions a future of commerce based on decentralization and peer-to-peer networking. Its offerings allow individual users to bypass the banks or other clearinghouses usually needed to process exchanges of goods, services, and Bitcoin currency. In step with their libertarian ethos, they do this by means of the same decentralized cryptocurrency that put blockchain technology on the world stage. The company makes and sells small computers with starter blockchain coding and built-in tools that bring the technology directly to the consumer. They embody the “disruptor” ethos of the Silicon Valley tech community.

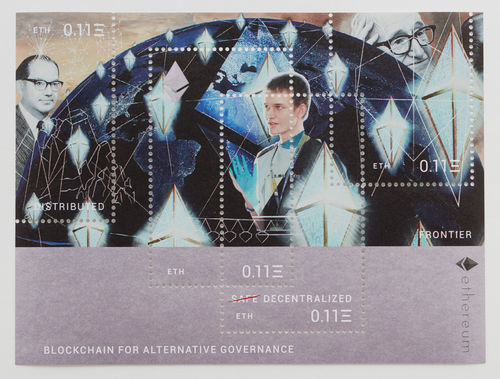

Launched by Vitalik Buterin in 2013, Ethereum is the most radical of the three organizations. It is supported by the Ethereum Foundation, a nonprofit based in Zug, Switzerland, that was created to build capital for the Ethereum platform. As part of the launch, the company sold Ether, an alternative cryptocurrency to Bitcoin, in exchange for financial backing. In addition to its own developers, the platform is supported by users who have acquired Ether and continue to grow their holdings through their contributions toward building the blockchain. The names of their building phases, tools, and technology are drawn from science fiction and fantasy. The software is free and has an active community of individuals who are interested in exploring the furthest possibilities of the technology, potentially replacing not just monetary systems, but organizational practices of all kinds.

For each of the companies, Denny has created a sculpture, based on the typical tech fair trade booth, and a brand identity that conveys the tenor of their work. Digital Asset’s design is classically symmetrical, in monochrome blue with white text in easy-to-read sans-serif lettering. Clean and polished, the booth offers a reassuring view of a solid company. It even features an illustration of the Bitcoin with a slash through it, signaling that they will protect the status quo. 21 is utilitarian and sleek with a minimalist design that is less symmetrical than Digital Asset’s, and more open in its lack of solid walls. The booth is slightly elevated and skeletal, much like a concert stage. The backdrop offers an aerial view of Silicon Valley’s shoreline, and the company’s Bitcoin miners form the “clouds” floating above. For Ethereum’s booth, Denny illustrates the popular tech idiom of “software eating the world” by ripping up the gallery’s carpet and applying it to the wall as a backdrop, exposing the flooring to view in the same way that the company opens up the workings of the blockchain to its users. The Ethereum logo is rendered in spray paint by a graffiti writer, and textured aluminum modular forms resembling shipping pallets are used as platforms, pointing to the adaptable nature of the company’s blockchain.

In addition to standing cutouts of its respective founder, each sculpture features a postage stamp design. Denny worked with the German stamp designer Linda Kantchev to imagine postage stamps for each company, lending another level of seeming veracity to the overall look of these works. With the new postage, Denny is proposing that each organization has the potential to be a future state in its own right, with the power to produce and regulate currency, upon which its leaders might be featured, much like George Washington or Benjamin Franklin appear on US currency. Kantchev’s illustration of Blythe Masters in the Digital Asset booth even borrows the stippled monochrome technique from banknotes.

Each booth also contains a customized version of the board game Risk. Digital Asset’s version features a conventional world map as in the original game, but replaces countries with financial centers and deploys executives, financial reserves, and corporations as the warring game pieces instead of infantry, cavalry, and artillery. 21’s game takes place offshore, the goal being to progress through various stages of market dominance built on the cloud. It features a founder, a proprietary computer, and the decentralized network model as the playing pieces. Moving completely away from the known world, Ethereum’s game takes place within an idealized geometry representing the blockchain and uses pieces representing a futurist warrior, a Github/4chan/Reddit alien, and an ether-fueled spaceship. Each of these games features some kind of conquest and monopolization. The Ethereum game represents the existing governmental and banking systems as corrupt and totalitarian, but winning the game and redistributing power requires total domination of the platform. The object of the 21 version is to build offshore companies that can corner the tech market free of government jurisdiction. Digital Asset’s game presents a post–financial collapse world where banks are scurrying to hide and protect their holdings from federal and public scrutiny. In each instance, Denny’s invocation of the game board is an allusion to the type of global conquest that Risk sought to miniaturize for the purposes of home entertainment.

In each of the sculptural groupings presented in Blockchain Future States, Denny imagines a scenario in which blockchain technology has revolutionized finance, commerce, and contracting protocols. In this fictional future, an unregulated free market reigns supreme, but, as with many technological developments, a few companies at the forefront have cornered the market. The decentralized equality imagined in Denny’s introductory video remains the stuff of idealism. An emerging group of artists of Denny’s generation are imagining how current developments will play out, perhaps due to the rise of computer simulations, trend forecasting, and data analytics coupled with ubiquitous concerns over collapsing governments and economies. This focus on the future is in contrast to artists of Wilson’s generation who tried to recall the past in order to avoid the same mistakes moving forward. Among a younger generation, artists like Denny and groups such as the now defunct K-HOLE or the collective DIS create works and networks of information that give shape to new cultural forms. Rather than arguing against this overly informed, hypertechnological dystopia, they are laying it bare so that viewers can decide whether or not they want to willfully continue on that path.

Notes

1. Simon Denny, What Is Blockchain? (2016). Video, color, sound. 3 min. Dialogue spoken by the narrator.

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.