Hammer Projects: Sam Falls

- – This is a past exhibition

Los Angeles-based artist Sam Falls fills the Hammer’s lobby walls with lush landscape paintings made in all of California’s National Forests.

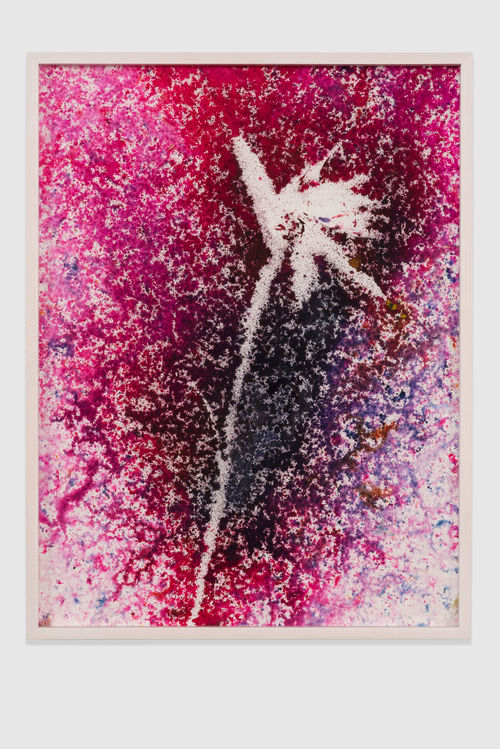

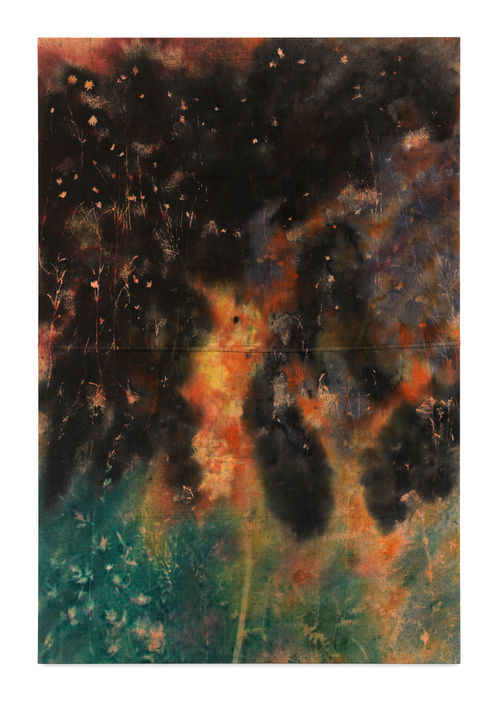

For California Flora (National Forest Condensation Wall), Los Angeles-based artist Sam Falls traveled to all nineteen National Forests in California to create a map of sorts that depicts the state’s flora, from the ocean to the desert, from volcanic topography to the forest floor. Working outdoors, Falls covers large canvases with vegetation from the sites he visits—Ponderosa pine trees, California buckwheat, deer fern, and wild bluegrass (to name a few)—and sprinkles them with dry pigments ranging from vibrant blues and bright yellows to more earthy hues, and then leaves them outside, exposed to the environment overnight. The condensation from rain or dew covers the surfaces in a process not unlike that used to create a photogram, requiring exposure over time so that only silhouettes of the flora remain amidst beautiful washes of color. Displayed together, the works are an immersive yet intimate portrait of the state of California that speak to the incredible heterogeneity of the landscape while compelling us to appreciate, care for, and maintain our invaluable ecosystems.

Hammer Projects: Sam Falls is organized by Anne Ellegood, senior curator, with MacKenzie Stevens, curatorial assistant.

Biography

Sam Falls (b. 1984, San Diego) lives and works in Los Angeles. He received his BA from Reed College in 2007 and his MFA from ICP-Bard in 2010. He has had solo exhibitions at Galerie Eva Presenhuber, New York (2017); Galleria Franco Noero, Turin (2017); Hannah Hoffman Gallery, Los Angeles (2016); The Kitchen, New York (2015); Ballroom Marfa, Texas (2015); Pomona College Museum of Art, California (2014); Public Art Fund, New York (2014); LAXART, Los Angeles (2013); and Printed Matter, New York (2012). His work has been included in group exhibitions at the Aspen Art Museum, Colorado (2017); the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio (2017); Mead Gallery, University of Warwick, England (2016); Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland (2015); the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2015); Museo MADRE, Naples, Italy (2014); International Center of Photography, New York (2013); High Desert Test Sites, Joshua Tree, California (2011), and many more.

Essay

By Anne Ellegood

“It speaks of a literal manifestation of presence in a way that islike a weather vane’s registration of the wind.” —Rosalind Krauss, “Notes on the Index, Part 2”

Sam Falls’s lush landscape paintings are a kind of masquerade. Despite the artist’s use of canvas and colored pigments, his procedure for making them shares more with photography than with any other medium. With an MFA in photography and time spent working in a commercial photo studio, he has acknowledged how aspects of photography are often catalysts for his work. Yet he has also spoken of the promiscuity with mediums and methods that artists today often embrace, and his desire to “bridge the gaps between photography, painting, and sculpture.”1 The works certainly encompass vital aspects of all these, which may prompt the question: Who cares about categories? Indeed, Falls’s output over the past several years reveals that he is in agreement with innovative artists of earlier generations who felt that to embrace a medium also means to push its limits. His landscape “paintings”—and particularly the large-scale project created for the Hammer’s lobby, California Flora (National Forest Condensation Wall) (2017)—are more than amalgamations of different mediums, or a hybrid of photography and painting. Rather, they seek to integrate specific genres of art, including landscape painting, Surrealist photograms, conceptual serial photography, Land art, and durational forms of performance. One might worry that this ambition to find a language encapsulating so many methodologies would result in work that is unwieldy or unresolved, but Falls has a kind of measured voraciousness, resulting in precise systems for making work while giving equal significance to the outcome: undeniably gorgeous and conceptually rich works of art.

In 2011, Falls began creating images by leaving works outside in the sun for sometimes months at a time. Yet despite this interest in slowing things down and forming a work over time, he continued to employ basic photographic methods, for instance framing a subject (or object) within a picture plane and exposing it to light in order to get an image. As with a photogram, the result was a silhouette of the original object, imprinted onto the surface like a shadow of its former self. These works were a reaction of sorts against the spontaneity of much photography—its ability to capture fleeting moments—but still contained an element of chance in that there was no way to know exactly how the “photograph” would look until it was “developed.” Soon thereafter Falls began to experiment with condensation in the form of rain or dew as another environmental condition that could act as a tool to create images. He laid canvas drop cloths on the ground outdoors, covered them with vegetation sourced from the immediate surroundings, sprinkled them with dry pigments (the colors chosen randomly from an array of jars at hand), and left them exposed for a period of time. The precipitation caused the pigments to bleed on and around the vegetation and absorb into the canvas, creating verdant, colorful abstractions reminiscent of Color Field paintings, with thick bands of washy color. They also recalled Abstract Expressionism—such as Jackson Pollock applying layers of paint to a horizontal plane—yet in this case the marks were made by the tree branches, leaves, grasses, or other materials that were subsequently removed.

Falls has created these landscapes in a range of locations, including his backyard in Venice, California; the land surrounding his mother’s house in his home state of Vermont; upstate New York; and Sarvisalo, Finland, while he was an artist in residence there. The indexical quality—the way the works are a physical manifestation of their referent—give them a specificity with respect not only to site but also to time, duration, and action, underscoring what the theorist Roland Barthes calls the “having-been-there” quality of photography.2 In other words, with Falls’s works, we understand that the image before us is the result of a carefully orchestrated series of actions and physical conditions. Although we are not witnesses to the process itself, the work is evidence of what took place, a distillation of a complex system that exudes a pronounced sense of presence and stands in place of a previous event.

California Flora (National Forest Condensation Wall) is a map of sorts that covers the lobby walls and depicts the state’s flora from the ocean to the desert, from volcanic topography to forest floor—Ponderosa pine trees, valley oak, California buckwheat, deer fern, coyote brush, redwood sorrel, and wild bluegrass, to name only a few. To make this massive work, Falls traveled to all nineteen National Forests in California over the course of three road trips, hiking and camping in a different one each night. With its focus on mapping the specificities of the California landscape, the project brings to mind a seminal work of conceptual photography: John Baldessari’s The California Map Project (1969). Baldessari began with a printed state map and noted where the letters of the word “California” fell geographically. Traveling to each location, he used available natural elements such as rocks, sand, and flowers to create forms that resembled the letter that corresponded to that location on the physical map, and photographed it. When displayed, the photos are arranged sequentially to spell out “California,” creating a playful correspondence between language and site. Like Baldessari, Falls gave himself a set of rules in order to produce his work and deployed photographic processes in its realization. Yet his map is presented as a large-scale installation that is far more immersive and cinematic. Rather than adhering to the photograph in the way Baldessari did, Falls pushes into the realm of the painterly.

Rosalind Krauss once likened the impulse toward diversification and pluralism in art—what she called “willful eclecticism”—to a desire for “personal freedom” and “individual choice.”3 For instance, in the architectural cuts of Gordon Matta-Clark and the large-scale rubbings of Michelle Stuart she saw a kind of seriality unfolding across space that she associated with cinematic narratives. Falls’s desire to enact a photographic process but forgo presenting the work as an actual photograph may be the outcome of his own search for personal freedom. His solitary forays into the wilderness and physically demanding and time-consuming processes of hiking, gathering, scattering, and then waiting recall earlier works by artists like Richard Long and Hamish Fulton that embraced the walk as a primary component. Notably, their processes also engaged photography as a medium, but readily translated it into sculpture, drawing, and language.

Falls’s work also conjures the transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson, or Jack Kerouac’s countercultural urge to hit the road, each a distinct examination of the individual’s relationship to nature and the American landscape. The material manifestations of Falls’s actions are so closely tied to the environment that they function almost like a mirror of it—reflecting through a process of imprinting—yet at the same time they manage to wholly transform the original objects to become an accumulation of experiences. Taken as a whole, the work practically vibrates off the wall with its intense opticality, immersing us in something wholly new and unfamiliar.

Notes

1. Press release for Sam Falls, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, 2014.

2. Roland Barthes, “Rhetorique de l’Image,” Communications, no. 4 (1964): 47.

3. Rosalind Krauss, “Notes on the Index, Part I,” in The Originality of the Avant-

Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985), 196.

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.