Hammer Projects: Andrea Büttner

- – This is a past exhibition

German artist Andrea Büttner embraces various artistic media, from traditional practices, including woodcuts and glass painting, to more recent methods, such as video, performance, and installation. This confluence of visual styles and approaches affords her the opportunity to address fundamental questions of what it means to be contemporary, what philosophical stakes come with being an artist, and how one creates a representational image. Büttner’s commitment to simple gestures and modest forms of production grants her work the ability to “fall down,” as she puts it, or lie low enough for audiences to relate to her vulnerabilities. This exhibition brings together a constellation of new woodcuts and photographic works that relate to ideas of littleness and humility, as experienced in nature and language and as depicted in art historical representations of shepherds.

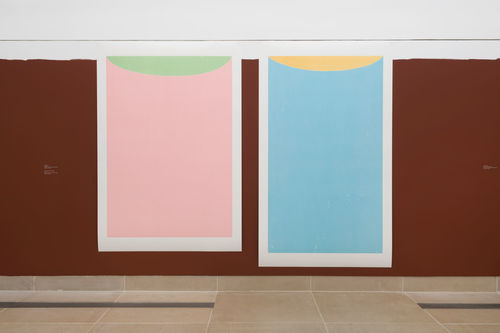

In Brown Wall Painting (2006/2017), Büttner announces the slightness of her physical stature by applying brown paint on the walls only as far as her hand can reach. The messy brown finish resembles an unprofessional paint job or, symbolically, a stain smeared on the wall. By making public her physical limitations in relationship to the conditions of exhibition and display, Büttner’s somewhat sloppy insertion of her hand upends the heroic gesture typically associated with the dominant histories of art. The haphazard application of paint on the gallery wall evokes Büttner’s inadequacies in ways that accept and embrace self-doubt as part of the process of making and exhibiting art.

The brown paint installation serves as a context for her woodcuts, such as I have no works (2017). Given that it is one of many works of art on display, the woodcut’s self-effacing title is ironic. This play on language is a reflection of Büttner’s suspicion of authorship and the aesthetic value systems applied to art. Similarly, Shepherds and Kings (2017) is an edifying installation in which two projectors cycle through images of nativity scenes depicting kings, wise men (or magi), and shepherds humbling themselves before Jesus. In form, Shepherds and Kings is the embodiment of the comparative iconographic study developed by art historian Erwin Panofsky in the twentieth century. In several of the images of the adoration of the magi that Büttner has chosen, we witness a power shift, in which kings stoop in the foreground while shepherds stand upright in the background.

Religious themes recur in Büttner’s photographic series Painted Stones, a suite of images that includes the reproduction of Salvador Dalí’s painting of the crucifixion on a pebble, Christ au Galet (1959), among other works. Rephotographed from a computer screen, Painted Stones documents a genre of diminutive artworks—stone paintings from the history of art—through which Büttner pays homage to other artists who have embraced humble materials and modest means.

Hammer Projects: Andrea Büttner is organized by Aram Moshayedi, curator, with Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, curatorial assistant.

Biography

Andrea Büttner (b. 1972, Stuttgart, Germany) lives and works in Berlin and London. She has had solo exhibitions at Musée Régional d’Art Contemporain, Sérignan, France (2016); Kunsthalle Wien, Austria (2015); Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (2015); Tate Britain, London (2014); Museum Ludwig, Cologne (2014); Whitechapel Gallery, London (2011); and Institute of Contemporary Arts, London (2008). Her work has also been included in such notable exhibitions as Documenta 13, Kassel, Germany (2012); 29th São Paulo Biennial, São Paulo, Brazil (2011); Liverpool Biennial, Liverpool (2006), and in such venues as MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts (2017); Van Abbe Museum, Eindhoven, Netherlands (2016); and Aspen Art Museum, Aspen (2015). Büttner is currently a nominee for the 2017 Turner Prize.

Essay

By Aram Moshayedi

My first encounter with the work of Andrea Büttner was at the Mandrake, an artist-run bar in Los Angeles, where one of her woodblock prints hangs on the wall. Its rough-hewn white letters, tightly squeezed into a black rectangular background, announce All my favourite artists had problems with alcohol (2005). Installed above a table at the bar’s only booth, the line reads as a sales pitch to the Mandrake’s typical clientele—young artists and art students who identify success in the art world with the legends of superstar addicts like Kippenberger, Büttner’s compatriot, and LA’s own Jason Rhoades. Leaving aside the cliché of the modernist tortured soul, the statement—in the context of Büttner’s practice—reflects an interest in human weakness as well as Bütter’s own identification with the figure of the artist as inherently flawed.1 Beyond this, the work hints at a deep discomfort with the discourse of autobiography and authorship.

Büttner began making woodcuts in the 1990s, when the previous decade’s wave of neo-expressionism in Germany gave way to a revival of conceptualism, and deconstruction took over academe. “I started making woodcuts because they were the most uncool thing I could do,” Büttner has said.2 The medium was a favorite of the ultimate macho German painter, Georg Baselitz; furthermore, as woodcuts require intensive labor and tend to result in “something beautiful, something like an auratic object,” they were out of critical favor.3 A seemingly reactionary move, Büttner’s woodcuts would appear to stand apart from the rest of her work, which ranges widely across media and is indebted to the lineages of conceptual art, performance, and video. Yet, as evidenced by the print discussed above, Büttner’s woodcuts comment on the medium’s history while simultaneously expressing an ambivalence toward aesthetic judgment, in particular, that moment when critique calcifies into dogma and the particularities of personal modes of inquiry become canonized. Her prints should thus be regarded as another articulation of the school of art that privileges idea over representation, even as they reintroduce a rich and vibrant visual logic to the analytical process of making.

Büttner’s woodcuts often explore themes found in her work in other media. Communities of faith, a longstanding interest, form the focus of the videos Little Works (2007) and Little Sisters: Lunapark Ostia(2012); similarly, she has created numerous woodcuts that incorporate Christian iconography or refer to biblical scenes. These prints hark back to the medium’s medieval beginnings in northern Europe, when it was employed for the mass reproduction of religious illustrations. One intricate, five-color diptych, Vogelpredigt (Sermon to the Birds) (2010), depicts St. Francis of Assisi preaching to birds sitting in a tree; Untitled (Three Kings) (2012) is based on a twelfth-century stone carving of the wise men visited by an angel as they sleep. Despite their devotional subjects, however, Büttner’s bold images stylistically evoke the early twentieth century, when the woodcut was revived by German Expressionists.

As Büttner reflects on the position of woodcuts within the history of art, she also considers the conditions of their production and reception, a central concern throughout her work. The eight photocopies that make up HAP Grieshaber / Franz Fühmann: Engel der Geschichte 25: Engel der Behinderten, Classen Verlag Düsseldorf 1982, (HAP Grieshaber / Franz Fühmann: Angel of History 25: Angel of the Disabled) (2010), for instance, present archival images of groups of teenage boys from psychiatric homes looking at woodcuts by HAP Grieshaber, the renowned German printmaker who had died the previous year. The analytical lens of re-picturing the photographs allows us to see the process of interpretation between subject and object; furthermore, critic Louise O’Hare writes, the work reflects on “embarrassment as a condition of viewing.”4 Grieshaber himself stands for another historical moment in the lineage of woodcuts that Büttner constructs: He studied art in the 1920s, was banned from exhibiting by the Nazis, and became an outspoken pacifist and political activist; more personally, he led printing workshops at the monastery where Büttner would later attend school.

Although many of Büttner’s woodcuts display the skilled technique handed down to her by way of Grieshaber, at other times, she has opted for a reduced approach: Simple lines illustrate the title subject in Tent (2010) and Tent (Two Colours) (2012) while the triangular space of Corner (2011) is printed from three separate boards that fit together. In these crude approximations, a formalist preoccupation is foregrounded as the communication of extraneous ideas recedes. Despite their seemingly handmade quality, however, the craggy outlines of the tents were in fact made with an angle grinder, a power tool more often employed to cut through the material entirely. The print’s nearly solid fields of color reveal the plywood’s natural grain in a smattering of speckled dots and dark striations, recalling the “truth to materials” approach of the Arts and Crafts movement, which sought to attend to the intrinsic quality of each medium. Indeed, these woodcuts are as much representations of the plywood from which they are constructed as they are of any outside referent. In Keyhole (2013), a small white shape opens at the center of the print, presenting a stark contrast with the expanse of black ink that envelops it, which is only interrupted by a static-like noise—the irregular grain of the block’s surface.

Büttner’s approach differs from that of Sherrie Levine, whose Knot Paintings, first made in the mid-’80s, demarcate the plugs embedded in plywood with the direct application of paint or lead, forcing an encounter with their physical properties. Or think of Wade Guyton’s works in wood, such as his 2008 edition for Parkett: a standard sheet of two-by-eight-foot plywood swathed in solid, shimmering black ink that varies in intensity according to the wood’s grain. Unlike these sculptural examples, in which wood forms a base structure that is obscured by pigment, Büttner’s prints provide access to the wood’s image but not its material presence. The keyhole offers a view of the white surface of the paper while the flat field it pierces indexes the material upon which the entirety of the encounter relies. In fact, Büttner often attempts to even out the block’s surface, filling in its holes and depressions, before she makes her prints. For her, the roughness no longer looks authentically handmade but instead appears “too finished-looking”—like a Photoshop filter intended to make a digital image seem like it’s from a bygone era.

If ambivalence and antagonism initially led Büttner to woodcuts, her reasoning has since evolved. “I am no longer interested in reacting to commercialized visual culture,” she explains. “I do the woodcuts now because I like them.”5 Büttner’s words, which propose subjective taste in place of theoretical argument, echo the relentlessly affirmative language of digital culture—Facebook and Instagram, after all, provide the ultimate forum for “liking,” for pledging an allegiance to a consensus of tastes. But while woodcuts are historically associated with accessibility and populism, the medium is decidedly out of touch with the speed and spread of today’s image production. Büttner’s prints instead speak of slowness, materiality, and preciousness, insisting on a modesty of means seemingly at odds with the demands of the global art world.

And yet, these very qualities situate the woodcuts squarely within our contemporary moment, as the rise of the digital has been met by the forceful reassertion of the “beautiful, auratic object,” which now proliferates in numerous analog forms.6 Even critical discourse has shifted in parallel, as exemplified by Jan Verwoert’s hypophoric proposition, “Why are conceptual artists painting again? Because they think it’s a good idea.”7 In the end, it might be impossible to maintain a contrary position in today’s all-embracing, all-consuming art world. Büttner thus grapples with the very notion of what it means to be contemporary, and the contradictory demands placed on artists in the hypersphere that defines contemporary art today. If the question of relevance were to be asked of Büttner’s woodcuts, the answer would probably have something to do with an uncool faith in the power of art and, paradoxically, the conceptual gestures that propel this faith forward into the future.

Notes

1. These themes have been written about at length by Martin Herbert, among others. See Herbert, “Angle of Repose: Martin Herbert on the Art of Andrea Büttner,” Artforum, March 2015, 269.

2. Andrea Büttner, quoted in Gil Leung, “Artists at Work: Andrea Büttner,” Afterall, May 25, 2010, www.afterall.org/online/artists.at.workandreabttner.

3. Büttner, quoted in ibid.

4. Louise O’Hare, “Not Quite Shame: Embarrassment and Andrea Büttner’s Engel der Geschichte,” Afterall, Summer 2014, 110.

5. Büttner, “Artists at Work.”

6. See Claire Bishop, “Digital Divide: Contemporary Art and New Media,” Artforum, September 2012, www.artforum.com/inprint/issue=201207&id=31944

7. Jan Verwoert, “Why Are Conceptual Artists Painting Again? Because They Think It’s a Good Idea,” Afterall, Autumn/Winter 2005, www.afterall.org/journal/issue.12/why.are.conceptual.artists.painting.again.because

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.