Hammer Projects: Nicolas Party

- – This is a past exhibition

Swiss artist Nicolas Party to create a site-specific wall mural for his first exhibition in Los Angeles.

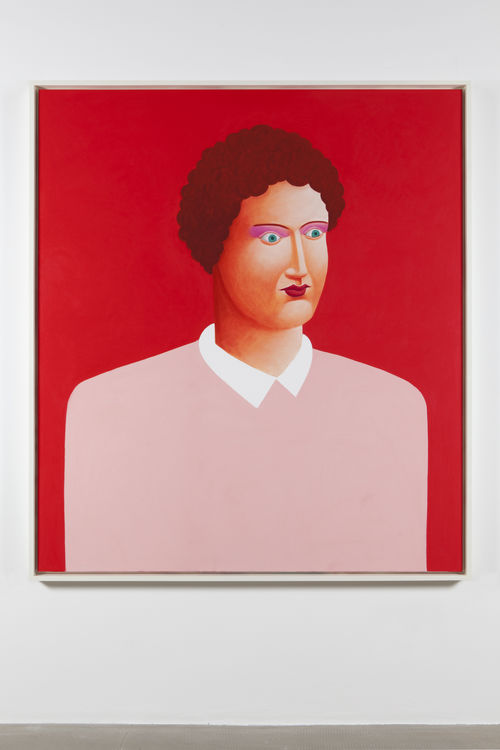

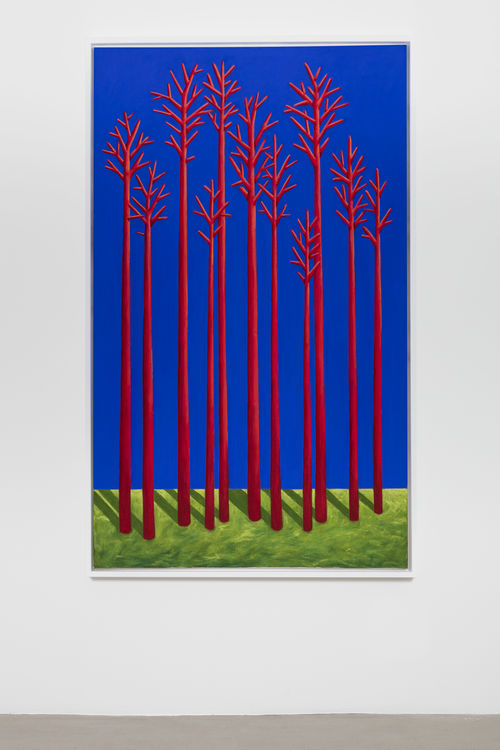

In his paintings and murals, the Swiss artist Nicolas Party revitalizes traditional genres such as still life, portraiture, and landscape. He has developed a signature aesthetic featuring a vibrant palette and a flat, graphic style that is immediately recognizable. His art historical influences include medieval art (specifically the flat figures in religious paintings of the period), as well as the work of late nineteenth-century painters such as Félix Vallotton and Ferdinand Hodler, and the early twentieth-century painter Balthus. One of Party’s more contemporary influences is the multimedia artist John Armleder, whose continual blurring of the lines between decoration and high art is also a persistent consideration for Party as he wrestles with the limitations of painting and the weight of history.

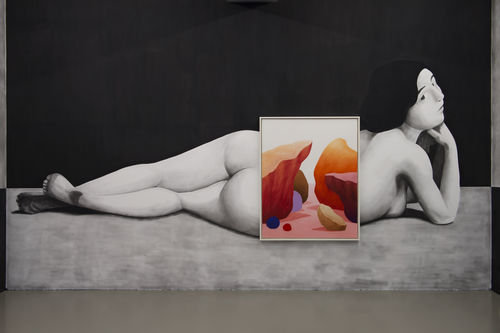

Party’s work slips between the past and the present, nostalgic and futuristic. A classically trained painter, he experiments with techniques such as fresco, gold leaf, and more recently marbling. He selects colors and animals for their symbolism and specific references. In addition to art history and decorative traditions, Party also considers the natural environment and the social context in conceiving his exuberant murals. For one exhibition, he used a mural to create a set for his show. Playing on the idea of the post–opening reception dinner, he produced tables and chairs painted with elephants and littered the floor with painted sculptures of fruit—a nod to the after-party detritus. While some of Party’s murals function as backdrops for exhibitions—he often hangs his paintings on walls that he has painted with decorative elements—others, like the one he will create for the Hammer Museum’s lobby wall, take center stage. This will be Party’s debut exhibition in Los Angeles.

Hammer Projects: Nicolas Party is organized by Ali Subotnick, curator, with Emily Gonzalez-Jarrett, curatorial associate.

Biography

Nicolas Party (b. 1980, Switzerland; lives and works in Brussels) received his MFA from the Glasgow School of Art and his BFA from the Lausanne School of Art in Lausanne, Switzerland. He has exhibited widely in Europe and the U.S. with solo exhibitions at Centre d’art Neuchâtel, Neuchâtel, Switzerland; Dallas Museum of Art; Inverleith House, Edinburgh; Kunsthall Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway; Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster; Swiss Institute, New York; and La Placette, Lausanne. His work has been featured in group exhibitions at Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, Germany; Kunstzentrum Glasgow; Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany; Eastside Projects, Birmingham; and Le Quartier Centre d’Art Contemporain, Quimper, among others.

Essay

The late nineteenth-century painter Henri Rousseau often depicted timeless landscapes of abundant foliage populated with monkeys, tigers, lions, and the occasional human, which transport viewers into an alternate universe. Often derided for having been executed in a naive or primitive manner, Rousseau’s animals and humans bear a resemblance to the awkward, flat figures in medieval paintings, for instance those featuring the Virgin Mary cradling a baby Jesus who looks more like an elderly man or a half alien than a divine infant. That distinctly flat style may have been the result of underdeveloped techniques, but the aesthetic resonates deeply with the contemporary painter Nicolas Party.

Painting is the starting point for all of Party’s work. Classically trained (with an early background in graffiti art), he is extremely conscious of the medium’s connection to history. While his work might appear effortless on the surface, Party sometimes spends one or two years working on an individual oil painting. He’s also highly cognizant of the technical aspects of the practice and is proficient in a variety of mediums, including pastel, oil paint, spray paint, charcoal, watercolor, and gold leaf. He often combines techniques to create unexpected illusions and interactions—recently he began incorporating faux marble and faux wood grain into his murals.

Party revitalizes traditional genres such as still life, portraiture, and landscape while embracing the aforementioned flatness of medieval art. Other key art historical influences include late nineteenth-century painters such as Félix Vallotton, Ferdinand Hodler, and Claude Monet, and the early twentieth-century painters Balthus and Giorgio Morandi. Morandi, a highly revered still life painter, has been especially influential for Party in terms of his approach to composition and ability to focus and concentrate a kind of quiet attention—his own and that of his viewers. As Party notes, Morandi’s “objects are always in the centre of the canvas, like a group of performers on stage.”1

Party’s signature aesthetic, distinguished by a vibrant palette and flat, graphic imagery, feels somehow fresh and new even while it references the past. Indeed, his paintings cannot be situated in a specific time period. The objects depicted—jugs, pitchers, pots, and other vessels—don’t connect to any particular era of design, enabling them to occupy a kind of limbo where there is no past, no future. And while he paints from imagination, he selects his depicted objects deliberately. He paints pots, for instance, because “representing an object that contains something you can’t see…interests me. You have to imagine it.”2 These vessels, like the medium of painting, have a long history and have appeared in some form in nearly every known human culture. In the artist’s words, their “form and function have not really changed and have been shown a million times in the past.”3 And while retaining his flat style in depicting these objects, Party also creates an illusion of weight and volume, most likely owing to his previous work in 3D animation. The food Party represents—sausages and a variety of fruits—is also timeless, for the most part. At least as far as produce is concerned, things haven’t changed much throughout history (aside from the advent of GMOs). Even his portrait subjects, their elongated, gender-ambiguous super-flat figures reminiscent of those awkward medieval baby Jesus paintings, don’t include signifiers connecting them to any specific time or place.

One of Party’s more contemporary influences is the multimedia artist John Armleder, known for blurring the lines between decoration and high art. This manifests, for example, in the patterning that plays a significant role in Party’s work, providing a backdrop in some cases and taking center stage in others. Repeated shapes and colors transform the white cube into a buzzing, ecstatic environment that totally envelops us as viewers. For Decorative Graffiti (2014) Party painted the exterior glass walls and the walls behind the windows of the Westfälischer Kunstverein in Münster, Germany, with repeating black and white spray-paint drips, transforming the space into a dizzying echo of itself. The inside mirrored the outside, the paint on the windows casting shadows to multiply the effect.

In addition to art history and decorative traditions, Party considers the natural environment and the social context when planning his exuberant murals, approaching his installations like a stage director. He appreciates the theatrical potential of wall paintings and installations, conceiving of the subjects of his work, whether people or objects, as performers on a stage—especially when they’ve jumped off the canvas. His wall paintings provide a backdrop for the framed paintings, which become like characters and props in the play. For the exhibition and performance Dinner for 24 Elephants at the Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland (2011), as well as Three Elephant’s Day at Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, Germany (2014), Party turned what might have been a staid affair into a dynamic Gesamtkunstwerk. He created all of the elements for the dinner, including the tables, chairs (elephant stools), and dishes. Once the dinner guests arrived, they completed the set, putting the play into motion.

A good-luck symbol in several cultures, elephants feature prominently in Party’s installations, as in Trunks and Faces at the Westfälischer Kunstverein (2014), Still Life, Stones and Elephants at the Swiss Institute in New York (2012), and Dinner for 24 Elephants. The Swiss Institute exhibition included elephant stools; at Trunks and Faces, the elephant stools grew dramatically into tall (more than thirteen feet high) columnar pieces with stilt-like limbs, their rear ends and curly tails prominent. One fit snugly into a corner; another was against the wall between two paintings, its elephant legs echoing the long, skinny birch trees in the adjacent painting. Two others flanked an open doorway, imparting the feeling of walking under the animals’ legs when one passed through the threshold. As the elephant works demonstrate, there is a subtext of humor and playfulness in Party’s work, yet he never ventures too far into the terrain of make believe or the absurd.

Along with timelessness, there is a celebratory nature to Party’s imaginary worlds of decadent foliage, alluring produce, and colorful characters. Radically transforming a space to create a total sensory experience, his murals are ambitious and dynamic yet playful projects. Reflecting on the thirteenth-century theorist Leon Battista Alberti’s idea that “painting is like an open window to the world,” Party notes, “When you dispose paint on a surface, that surface opens, like a window into another dimension.”4 Party’s enveloping wall paintings indeed transport us into another dimension: his own private world, devoid of clocks and calendars.

—Ali Subotnick

Notes

1. Nicolas Party and Jesse Wine, “Apples and Pairs,” frieze, no. 175 (November–December 2015): 108.

2. Elise Lammer, “Sweetgeranium: Interview with Nicolas Party,” Novembre Magazine, no. 3 (Spring–Summer 2011), http://novembremagazine.com/sweetgeranium-by-nicolas-party-interview-by-elise-lammer.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.