Hammer Projects: Marwa Arsanios

- – This is a past exhibition

Through architectural renderings and models, video, and topographic maps, the artist Marwa Arsanios addresses the changing landscape of Beirut, the city where she lives and works, which has been marked by the rapid development of its urban spaces and burdened by a recent garbage crisis. Drawing a parallel between two distinct narratives in Beirut’s recent history, Arsanios’s research takes aim at the aftermath of the neoliberal project that took shape at the beginning of the 1990s, in the years immediately following the end of Lebanese Civil War. After the closure of Naameh landfill outside of the city in summer 2015, thousands of tons of garbage filled the streets of Beirut and Mount Lebanon, leading to public outcry and accusations of government corruption. Although the recent growth of art museums and other cultural institutions throughout the city, alongside a boom in commercial real estate development, has increased Beirut’s international profile, a number of building projects remain fallow, and overflowing landfills threaten the city’s environment and the health of its population. A new project by Arsanios speculates on these developments as part of ongoing issues in Beirut’s history, while pointing to the broader political, social, and cultural implications for Lebanon.

Hammer Projects: Marwa Arsanios is organized by Aram Moshayedi, curator, with MacKenzie Stevens, curatorial assistant.

Biography

Marwa Arsanios (b. 1978, Washington DC, lives and works in Beirut, Lebanon) received her MFA from University of the Arts London in 2007, and was a researcher in the Fine Art department at Jan Van Eyck Academie from 2011 to 2012. She has had solo exhibitions at Witte de With, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (2016), Kunsthalle Lissabon, Lisbon (2015), and Art in General, New York (2015). Her work was also shown at the 55th Venice Biennale (2013), the 12th Istanbul Biennial (2011), Home Works Forum in Beirut (2010, 2013, 2015), the New Museum, New York (2014), M HKA, Antwerp, Belgium (2013), and nGbK, Berlin (2012). Screenings of her videos have taken place at the Berlinale, Berlin (2010, 2015), e-flux storefront, New York (2009), and Centre Pompidou, Paris (2011). In 2012 Arsanios was awarded the special prize of the Pinchuk Future Generation Art Prize.

Essay

By MacKenzie Stevens

In February 2016, after a seven-month closure, the Naameh landfill—one of the primary garbage dumps in Beirut—reopened. Residents in the surrounding neighborhoods had long advocated for the landfill’s permanent closure, citing concerns of smell, poor air quality, and environmental pollution, and in July 2015 the government finally acquiesced. But when an overwhelming volume of trash subsequently filled the city’s streets, threatening the water supply and causing a public nuisance, protests and accusations of fraud, corruption, and ineptitude erupted among a populace already lacking confidence in the government. “It’s not about money. It’s the political situation and the

conflict in the country…. It’s a mess, it’s chaos. We cannot work,” remarked one Environment Ministry worker to The National. (1) With no other plan to deal with the city’s trash, the government reopened Naameh, and created other landfills.

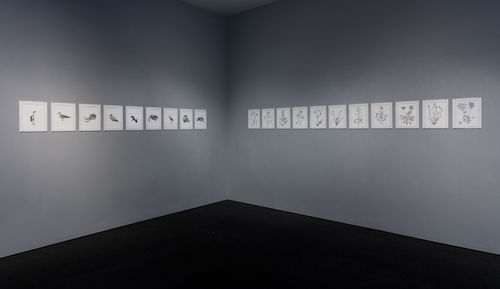

Marwa Arsanios’s current body of work contends with the garbage crisis in Beirut, visualizing it in digital video, small topographical models of the city’s landfills, and a suite of drawings of the flora and fauna that exist in these dumps despite their toxicity. Arsanios points to the ways in which the landfills are connected to the wide-scale redevelopment of Beirut that began after the Lebanese Civil War ended in 1990. Since then, several of these landfills have become new expanses of land that extend the city’s natural coastline.

The troubled inner workings of the Lebanese government are not new. Even amid an atmosphere of hopefulness after the civil war, corruption persisted. With the election of businessman Rafic Hariri as prime minister in 1992, a massive reconstruction and re-urbanization project for the city of Beirut began under the auspices of Solidere, a company in which Hariri was a shareholder. In addition to the renovation of war-battered monuments and museums, the construction of new high-rises was part of an effort to rejuvenate the country’s crumbling economy, bring tourism back to Beirut, and restore its former status as the “Paris of the Middle East.” Hariri’s death in 2005 and the start of the Israeli-Lebanese war in 2006 led to a dismantling of Hariri’s pro-business regime (although Solidere continues to function), leaving a string of incomplete project and further privatization of development in Beirut.

Arsanios’s topographical models of the Karantina and Costa Brava dumps show only the most basic contours and features of these sites, suggesting that they are simply empty spaces to be filled. The models are meant to function as “cartographies of extended lands,” in the artist’s words, that will become “inaccessible islands built on rubble and garbage, where real estate havens will be created. These will most of the time remain empty because people will buy them as assets or investments. They will be ‘Gated Islands’ of money made out of garbage.” (2) The process of transforming these landfills into “Gated Islands” of money—made out of, and on top of, trash—will displace the current residents. The models are therefore renderings of land in transition that provide a unique kind of access to the sites because they offer a view from above. The aerial view is disorienting, as the land is scaled down to an almost insignificant size. The models disconnect the landfills from the surrounding city while transforming them into tracts of land primed for development. Trash, and, perhaps most importantly, people, are omitted.

The aerial view has a long and complex history, signifying expansion and control, and the development of empire. During the age of exploration and European colonization of the Americas and Africa, mapping was a vital tool for conquest, and the aerial view was particularly important, as it reduced large swaths of land to tidy parcels. In the twentieth century, aerial photography became a crucial tool for warfare, ushering in a new form of mapping that privileged military demands. The long history of the aerial view is invoked by Arsanios’s models, suggesting power and economic growth. The models show that the landfills are actually part of a new form of empire building thinly veiled as redevelopment and capitalist progress.

In her project for the 12th Istanbul Biennial, All About Acapulco (2011), Arsanios included an architectural model of the Chalet Raja Saab in order to address the changing landscape of Lebanon’s coast. In the artist’s words, models allow her to “bring existing buildings and spaces back to a certain pre-construction state—back to the thought process.” (3) Reducing an actualized building to a thought deflates it, reconstituting it as a form not yet bogged down by the accretion of histories that all built structures eventually acquire. Photographs and newspaper clippings accompanied the exhibition, providing the narrative that the model alone cannot: Designed by the Lebanese architect Ferdinand Dagher, the Chalet Raja Saab was constructed in 1950 on Beirut’s southern “gold coast,” known as Acapulco Beach. The structure served as a single-family dwelling, after which it became the Acapulco Beach Resort, then finally it returned to its original function as a domestic space—but this time for four families, not one.

The model, the centerpiece of All About Acapulco, was suspended in the middle of the room, reinforcing its centrality to the history of this site. The eleven cacti placed below it alluded to the kinds of tropical foliage that punctuated the Acapulco Beach Resort in its heyday. The installation conveyed a particular nostalgia for a moment before the onset of the Lebanese Civil War, prior to the destruction that ensued.

In Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory, the cultural theorist Andreas Huyssen writes about the ways in which the past and the present, the imagined and the real, are intertwined within cities, monuments, architecture, and sculpture: “One of the most interesting cultural phenomena of our day is the way in which memory and temporality have invaded spaces and media that seemed among the most stable and fixed: cities, monuments, architecture, and sculpture…memories of what there was before, imagined alternatives to what there is. The strong marks of present space merge in the imaginary with traces of the past, erasures, losses, and heterotopias.”4 Arsanios’s All About Acapulco suggests that an assembly of an architectural model, photographs, and newspaper clippings can also function as a site for memory and histories of conflict.

The Chalet is one of the few beach dwellings that remained intact after the Lebanese Civil War. Others, such as the St. Georges and the Hotel Normandy, were almost entirely destroyed. The Normandy’s rubble, as Arsanios explains in her video Falling is not collapsing, falling is extending (2016), was piled into the sea, later becoming the Normandy landfill, which is now a site for urban redevelopment. The new “Waterfront District,” consisting of high-end retail storefronts, condominiums, a beach resort, parks, and other built structures, will cover the Hotel Normandy’s remains.

The transformation of the Normandy is just one example of a long-term plan to overhaul Beirut’s war-torn spaces and reinscribe them as sites of progress and capital. Arsanios seeks to draw attention to the ways in which these activities are part of the legacy of the redevelopment project initiated by Hariri at the beginning of the 1990s. In describing the landfills and coastline extensions destined to become sites for expansion, Arsanios’s drawings, models, and essayistic video elucidate the layers of bureaucracy required to build an empire. The colonialist enterprise, it seems, is not so different from the notions of progress forwarded by the neoliberal boom.

Notes

1. Josh Wood, “Out of Sight, Out of Mind, but Lebanon’s

Rubbish Crisis Hasn’t Gone Away,” The National, August 13, 2015.

2. Email from the artist, July 31, 2016.

3. Ibid.

4. Andreas Huyssen, Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003), 7.

Hammer Projects is presented in memory of Tom Slaughter and with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.

Hammer Projects: Marwa Arsanios is produced in association with Beirut Art Center, with additional support from Milk.