The Afghan Carpet Project

- – This is a past exhibition

This exhibition is organized by curator Ali Subotnick with Emily Gonzalez-Jarrett, curatorial associate.

Essay

By Ali Subotnick

In the contemporary art world, the first name that comes to mind when one thinks of Afghan carpets is usually that of the Italian artist Alighiero Boetti, who began traveling to Afghanistan in the early 1970s and worked closely with weavers there and in Pakistan to make carpets of maps, grids, and other custom designs. While at the time Boetti was interested in using weavers, in part, as a way of removing his own hand from his art production, this project instead focuses attention on local artisans and the role of individual craftspeople in the production of this fine art. More recently contemporary artists have engaged with craft as a way of engaging with the histories and economies of labor and the handcrafted and their various associations with gender and the domestic. In March 2014, at the invitation of the Hammer Museum, six Los Angeles–based artists—Lisa Anne Auerbach, Liz Craft, Meg Cranston, Francesca Gabbiani, Jennifer Guidi, and Toba Khedoori—traveled to Afghanistan to visit weaving facilities and learn about the process and history of handweaving carpets, a traditionally female craft in the region. The trip grew out of a collaboration between the Hammer Museum and the Los Angeles–based carpet designer, Christopher Farr. Farr’s company had been invited to produce carpets in Afghanistan by Lisa Sanchez, founder of the nonprofit organization AfghanMade, which aims to revitalize traditional industries such as carpet weaving, cashmere production, and jewelry.

Carpets have been handwoven in Afghanistan for centuries and are the nation’s largest legal export. The craft is highly revered, and the traditional patterns and designs have remained mostly unchanged until recently, with growing exposure to modern and contemporary influences. In recent years carpet production has waned in Afghanistan, and most carpets woven there are washed, finished, and shipped from Pakistan. AfghanMade enlisted the renowned carpet expert Bulent Ozozan, who introduced many of the studios to industrial washers and taught them to cut and shave the carpets so that the quality met the standards demanded by high-end carpet producers around the world. Sanchez then invited a handful of respected carpet producers (including Farr) to make their carpets in Afghanistan. Farr proposed a collaboration with the Hammer Museum and worked with the museum to select the artists who would travel to Afghanistan and then create original designs to be made into carpets that would be handwoven there, exhibited at the Hammer, and sold, with the proceeds given back to support a charity for Afghan women. Many of the artists invited were eager for the opportunity not only to visit Afghanistan but also to collaborate with the women artisans who have developed the art of carpet making there.

Led by Sanchez, the Hammer group flew to Kabul. On the first day we visited a full-service carpet production facility that does everything from spinning and dyeing wool to hand-painting the carpet designs onto graph paper for the technical drawings and weaving on the looms. The third day was spent in Bamiyan, situated on the ancient Silk Route, best known as the home of the giant Buddha statues carved into the mountains in the sixth century, and destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. In Bamiyan we visited several studios and private residences where, in many cases, brothers and sisters worked side by side on the loom. All are affiliated with Arzu Studio Hope, a nonprofit organization that established weaving studios that pay women weavers double the wages that they had been making previously. Unlike traditional women weavers, those employed by Arzu receive their wages directly rather than through a middleman. The studios also provide the women and their children with health care, vaccinations, early childhood education, playgrounds, laundry facilities, and more. We were able to speak with a few of the women (most didn’t speak English or were too shy to speak), and they confirmed that Arzu had greatly improved their quality of life. After those visits it became clear to all of us that Arzu would be an ideal beneficiary of the proceeds from the carpet sales.

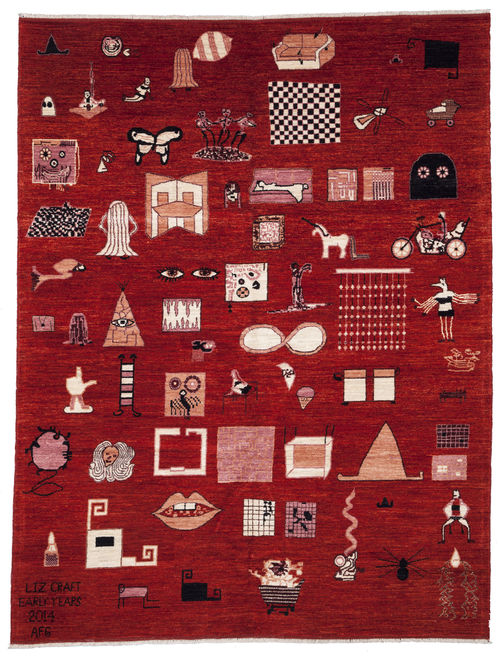

Each artist took a personal approach to her carpet. The knitter and photographer Lisa Anne Auerbach was already quite familiar with the techniques and challenges of translating a drawing into a woven image. Instead of using text, as she often does with her knitted works, she drew inspiration from traditional Greek and Roman mosaics illustrating gluttony with images of uneaten food and other detritus left on the floor following a grand banquet. Auerbach saw parallels between the crafts of mosaic and knitting, in particular a similar pixelation and distortion of the original image. Her design features crumpled plastic cups, cans, bottles, and rotten produce—the kind of trash she often finds outside her studio—with a border inspired by the ornamentation on the Fourth Street bridge in downtown L.A., near her Boyle Heights studio. Liz Craft had been thinking for years about putting together a retrospective of all her work but in miniature, and she had long been interested in Afghan war rugs, with their bright colors and crude line drawings. Like the war rugs that feature nontraditional motifs such as the World Trade Center towers, planes, missiles, bombs, and flags, Craft’s design features a drawn inventory of her sculptures (some of which were inspired by carpets) made since the late 1990s. She wanted her carpet to function as a marker of time with a narrative structure, similar to the diaristic quality often found in folk art.

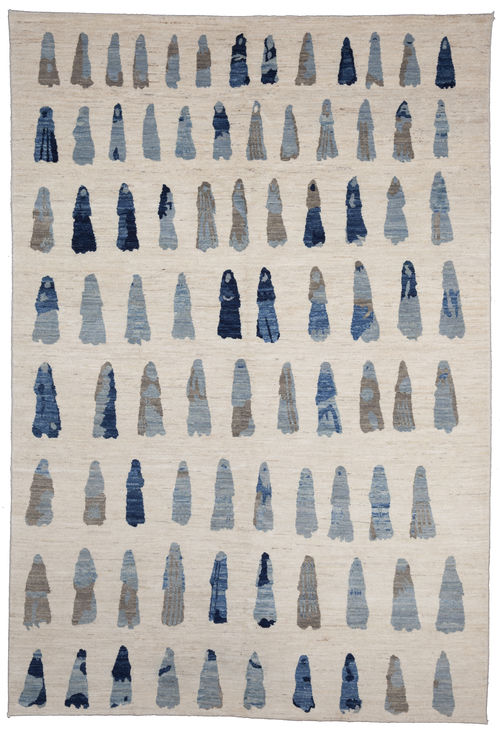

Over the last few years Meg Cranston’s work has focused on the sociology and history of color and how color is determined culturally and industrially. Serendipitously, when we were visiting Arzu Studio Hope in Bamiyan, she noticed a color chart on the wall of a preschool classroom. Cranston was struck by the colors, which were not the primary and secondary colors that are typically represented in American color charts but were instead the colors used in Afghan carpets. Continuing her interest in the study of color, Cranston made that chart the basis for her carpet design. Francesca Gabbiani was fascinated by the popular pastime of kite flying in Afghanistan and created an image featuring a mass of colorful kites floating on a white plane. As we drove around Kabul, Jennifer Guidi noticed women walking together in small groups, clothed in what seemed to be a uniform of full-length light blue burqas. During our stay in Kabul, Guidi made a watercolor featuring rows of the ghostly blue burqa–clad women. The watercolor mimics the repetitive marks that she makes in her paintings (originally inspired by the backs of carpets), yet it allowed her to use an image that came directly from her experience in Afghanistan.

Getting a firsthand view of the Hindu Kush mountains on our flight to Bamiyan confirmed Toba Khedoori’s interest in using one of her 2010 paintings of the mountain range for her carpet. Her design is the most complex in its detail, colors, shading, and intricate drawing, and when Ozozan saw the image, he knew that translating it to a woven carpet would be incredibly difficult, but he was keen to try. Though the carpet was still in production at the time of this exhibition, on view is the technical drawing for Khedoori’s carpet, which gives some indication of its intricacy and the expansiveness of its image.

It was challenging for all the artists to leave the safety of the United States and their families to travel to a war zone and then to trust the weavers with their original artworks. But this experience will undoubtedly have an influence on their work moving forward. It is our hope that the Afghan weavers, in turn, will be inspired to experiment and expand their craft as the market will support. It would be naive to think that this project will change anyone’s life dramatically, but by arranging a collaboration between contemporary artists and traditional weavers, and by supporting Arzu Studio Hope, we have tried to contribute to the region’s economic recovery and to encourage artistic experimentation within a long and inspiring history of carpet making in Afghanistan.

The Afghan Carpet Project was initiated by the nonprofit organization AfghanMade, along with carpet producer Christopher Farr, Inc. with the goal of collaborating with women weavers in Afghanistan.

The Afghan Carpet Project is made possible thanks to the generous support of Dori and Charles Mostov. Additional support is provided by Adam Lindemann.

Special thanks to Alisa and Kevin Ratner, Christopher Farr, Matthew Bourne, and Joseph Rainsford at Christopher Farr Inc., and Lisa Sanchez and Bulent Ozozan at AfghanMade.

For more information on the beneficiary of this project, please visit the Arzu Studio Hope web site: arzustudiohope.org